Suffragist, Abolitionist, Speaker, Editor

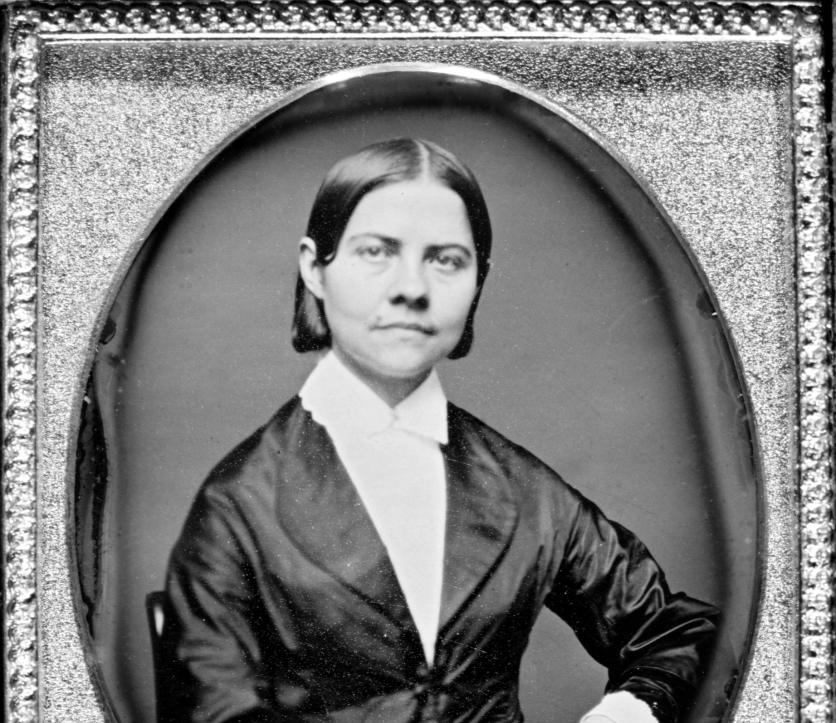

Called “the heart and soul” of the suffrage movement, Lucy Stone also made history as a public speaker, abolitionist, political organizer, and newspaper editor. As Massachusetts’ first female college graduate, a partner in an egalitarian marriage, and a determined and uncompromising advocate for equality, Stone embodied a new vision for American womanhood.

Lucy Stone was born on August 13, 1818 in West Brookfield to Francis and Hannah (Matthews) Stone. Her parents were farmers who passed on their Congregationalist faith and abolitionist beliefs to their nine children. Stone completed local schools by the age of 16 and was determined to continue her education, but her father refused to pay for further schooling for any of his daughters. Undaunted, Stone took up school teaching for several years in order to save enough money for tuition for further education.

Ohio’s Oberlin Collegiate Institute (later Oberlin College) had become the first college in the country to accept female students in 1837. Stone enrolled in 1843 and graduated in 1847, making her the first Massachusetts woman to earn a college degree. There, Stone discovered her passion for public speaking, but the college’s debating society was only open to men. Even when the administration asked Stone to pen an address for the 1847 commencement ceremony, they insisted that a man recite it in her place…so Stone refused to write it. While at Oberlin, Stone became actively involved in the movement to end slavery and even met the famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison at her graduation ceremony.

In 1847, Stone delivered her first public address on women’s rights, speaking at her brother’s church in Gardner. The following year, Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society hired Stone and sponsored her lecture tour across the state. Dismayed by her tendency to include issues of women’s rights in her abolition speeches, the society implored her to drop any mention of sex equality. Stone responded simply: “I was a woman before I was an abolitionist.” Stone and the Society reached agreement that she would split her lectures, speaking on abolition on the weekends and women’s rights on weekdays.

Stone served as one of the primary organizers for the first national convention for women’s rights, which took place in Worcester in 1850. (This followed the more regional women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls of 1848.) She also continued to lecture across the country for both abolition and women’s rights, advocating in the latter for temperance, dress reform, and greater rights for married women.

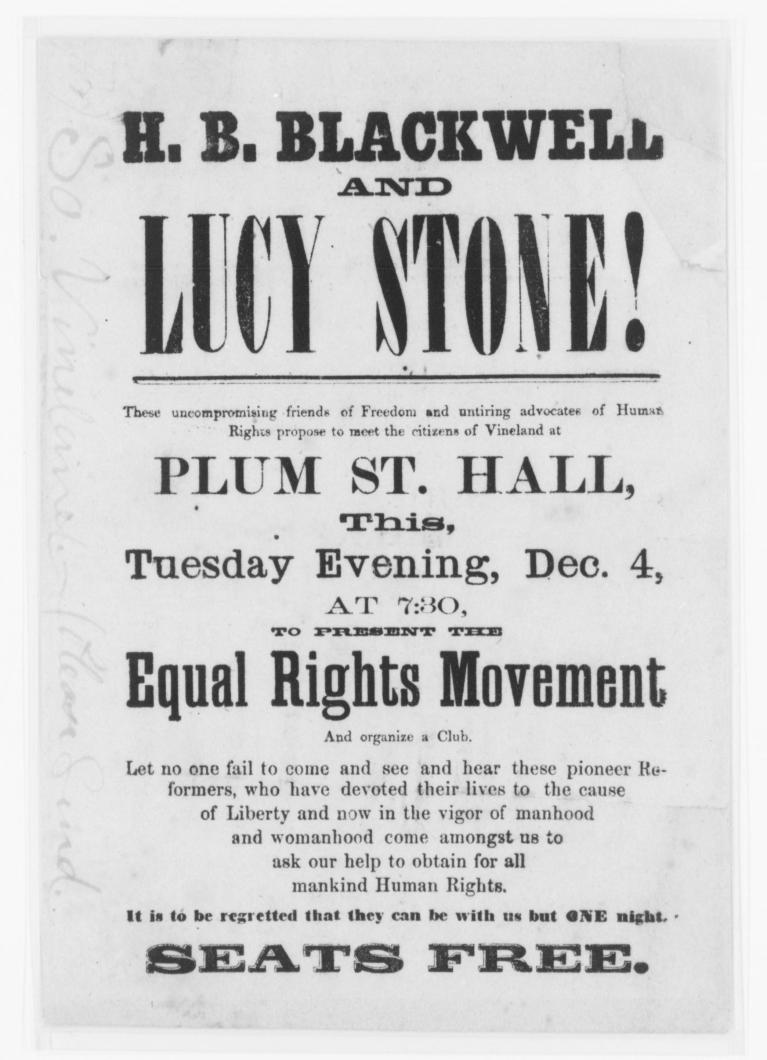

In 1853, Stone met Henry B. Blackwell, a merchant from Cincinnati who was also active in the abolition movement. Stone only agreed to Blackwell’s proposal after he promised that theirs would be an egalitarian marriage. The two wed in 1855. They omitted the word “obey” from their vows, added a statement refusing to acknowledge any law that restricted Stone’s independence within marriage (including the right to manage her own finances) and Stone kept her own surname after the nuptials. Before moving to Boston, the couple lived in Illinois and then New Jersey, where they had a daughter, Alice, in 1857. Alice Stone Blackwell went on to become a prominent suffragist and journalist in her own right.

Marriage and motherhood did not keep Stone from continuing to agitate for women’s equality. In 1858, while living in New Jersey, she refused to pay taxes while denied the right to vote. As a result, the town constable auctioned off her household goods in order to cover the debt. She also testified on behalf of suffrage before the state legislatures in New Jersey in 1867 and Massachusetts in 1869. In both cases, the special committees on suffrage issued reports in favor of enfranchising women, but the full legislatures rejected the measures.

Stone’s efforts on behalf of abolition and equal rights for African Americans continued through the Civil War. She co-founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) with fellow supporters of both abolition and women’s rights. Though Stone sought voting rights for all, she endorsed the 15th Amendment, which guaranteed the ballot for male citizens regardless of race, but not for women. Other suffragists, such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others, opposed the 15th Amendment. They were angry that it excluded women and they advanced racist, xenophobic, and classist arguments about the individuals the 15th Amendment would enfranchise. As a result, the suffrage movement split into two factions. In 1869, Anthony and Stanton formed the National Woman’s Suffrage Association (NWSA), while Stone, Blackwell, and suffragists Julia Ward Howe and Mary Livermore founded a competing organization, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), in order to work for suffrage rights without compromising on issues of racial equality.

The following year, Stone and Blackwell began publishing The Woman’s Journal. The official mouthpiece of AWSA, it eventually became the leading suffrage newspaper in the country. (Stone and Blackwell had moved to Dorchester in 1869 and The Woman’s Journal was based at AWSA headquarters in Boston.) Stone, Blackwell, their daughter, and other staff worked tirelessly to solicit advertisements and sell subscriptions in order to keep the costly yet vital voice of the suffrage movement afloat.

In her later years, Stone devoted much of her energy to The Woman’s Journal, but she continued to deliver suffrage speeches to legislatures, women’s clubs, and political conventions across the country. Stone passed away in 1893 at the age of 75.

While Stone passed away before her suffrage dream was realized, Alice Stone Blackwell continued the effort. In addition to running The Woman’s Journal, Stone Blackwell helped foster the reunification of NWSA and AWSA in 1890, resulting in the formation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA, along with the National Woman’s Party (founded in 1917) saw the battle through to its nationwide victory in 1920, more than 70 years after Stone began her suffrage activism.

Additional Resources

Lucy Stone Papers in the Woman's Rights Collection, 1846-1943. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Million, Joelle. Woman's Voice, Woman's Place: Lucy Stone and the Birth of the Woman's Rights Movement. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Academic, 2003.

Bibliography

Benstead, Amelia. “Lucy Stone (U.S. National Park Service).” https://www.nps.gov/people/lucy-stone.htm.

Berenson, Barbara F. Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Revolutionary Reformers. United States: History Press, 2018.

"‘A big baby always having to be fed and never growing up’: Lucy Stone and the Woman's Journal.” Massachusetts Historical Society. August 2019. https://www.masshist.org/object-of-the-month/objects/august-2019.

Blackwell Family. Blackwell Family Papers: Lucy Stone Papers, -1960; Speech, Article, and Book File, 1845 to 1891; Speech announcements. - 1960, 1759. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1288001981/.

Lasser, Carol. “Stone, Lucy (13 August 1818–18 October 1893), Abolitionist and Woman’s Rights Activist.” American National Biography. https://www.anb.org/display/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1500663.

McMillen, Sally Gregory. Lucy Stone: An Unapologetic Life. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Smith, Bonnie Hurd. “Lucy Stone.” Boston Women’s Heritage Trail. https://bwht.org/lucy-stone/.

“Suffrage and the Fifteenth Amendment.” Women & The American Story, New-York Historical Society. https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/fighting-for-equality/suffrage-and-the-fifteenth-amendment/