Professional Cook, Nutritionist, Teacher, Lecturer

by Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian

Cookery is the art of preparing food for the nourishment of the body.”

These words appear in Fannie Farmer’s most famous cookbook, The Boston Cooking School Cook Book, later known as the Fannie Farmer Cookbook. They highlight Farmer’s pioneering perspective on the role food and food preparation can play in individual health.

Born in Boston on March 23, 1857, Fannie grew up the eldest of four daughters to Mary Watson Merritt and John Franklin Farmer. She spent most of her youth in nearby Medford, where she was raised in a Unitarian household. Farmer attended Medford High School, with dreams of attending higher education cut short by an illness at age 16. This illness, which some historians surmise was polio, left her convalescing at home for several years. Her right leg was paralyzed, and, after regaining health, Farmer walked with a limp for the rest of her life.

With higher education no longer an option, Farmer sought to help her family bring in additional income. She worked as a helper to the home of a family friend in Boston, Mrs. Charles Shaw. Here, Farmer became interested and showed promise in cooking. Mrs. Shaw encouraged her to attend the Boston Cooking School. Established in 1879 by the Women’s Education Association of Boston, this school was designed “to offer instruction in cooking to those who wished to earn a livelihood as cooks, or who would make practical use of such instruction in their families.”

In 1887, Farmer entered the Boston Cooking School at age 31. Farmer quickly excelled at the school. She graduated after two years and stayed on as an assistant principal. In 1894, she became the head of the school. While head of the school, Farmer published The Boston Cooking School Cook Book in 1896.

The Boston Cooking School Cook Book became an unexpected hit as it revolutionized the American understanding of cookery. Farmer believed in the connection between diet and health, and that framing cooking as a science would produce better, healthier food. She used this book to educate the public on the nutritional value of ingredients and the importance of a balanced diet:

I certainly feel that the time is not far distant when a knowledge of the principles of diet will be an essential part of one’s education. Then mankind will eat to live, will be able to do better mental and physical work, and disease will be less frequent.”

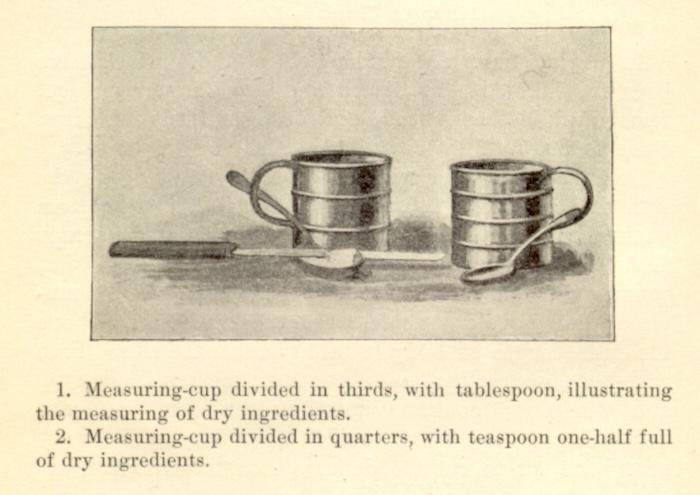

The book itself was comprehensive, covering all types of dishes from the basic to the complex. Farmer’s recipes were clear and concise, and she followed a standardized measurement system. Previous cookbooks had largely provided vague or imprecise measurements, such as a “heaping spoon” or a “handful,” assuming those following recipes had experience in cookery to use their best judgement. Because of Farmer’s adherence to precise measurements, she is often credited as the inventor of the modern recipe.

The wide success of the cookbook made Farmer independently wealthy for the first time in her life. She supported her family and used the funds to open her own cooking school, Miss Farmer’s School of Cookery, in 1902. Her school had four kitchens and a staff of 10 teachers. Farmer had an expansive student base, including: aspiring cooks, waitresses, young women, housewives, housemaids, nurses, and graduates of domestic-science schools.

By this time, Farmer had gained national recognition for her work in the field of cookery. She lectured at women’s clubs and community groups across the country and contributed to a monthly page in The Woman’s Home Companion with her sister Cora Dexter (Farmer) Perkins. Locally, Farmer offered weekly demonstrations at her school, taught courses to nurses and dietitians, and even lectured at Harvard Medical School.

Perhaps due to her own health issues, Farmer became increasingly focused on diets for people in ill health. Although publishing several other cookbooks, she considered her most important work to be Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent (1904).

Farmer suffered from several strokes in her final years, which left her in a wheelchair. She died in Boston on January 15, 1915, at the age of 57 due to complications from arteriosclerosis and kidney disease. The Holyoke Daily Transcript wrote in her obituary:

No woman in Massachusetts has done more to educate the women of her city and state in the way of setting good tables. She taught the essentials of good cooking and day after day, year in, year out, she could work out some new combinations of flavors that made eating a joy.”

While her life was cut short, Farmer’s ideology of cooking continued. Her cooking school operated until its closure in 1944. The Fannie Farmer Cook Book stands as one of the most reprinted cookbooks in the country, having sold over seven million copies and inspiring countless cooks and chefs (including another American cookery icon and a woman of Masssachuetts, Julia Child!). A 1994 revision is still in print. The book’s success fulfilled Farmer’s hope for its lasting resonance:

It is my wish that [this book] may not only be looked upon as a compilation of tried and true recipes, but that it may awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought and broader study of what to eat.”

Bibliography

“Expert in Cooking. Miss Fannie M. Farmer Dies in Hospital.” Boston Globe, January 16, 1915.

Farmer, Fannie. The Boston Cooking School Cook Book (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1896). Accessed via Feeding America: the Historic American Cook Book, Michigan State University.

“Fannie Farmer – Useful Woman.” Holyoke Daily Transcript, January 16, 1915.

“January 7, 1896: Fannie Farmer Cookbook Published.” MassMoments. Accessed November 2024.

Lincoln, Mary J. "The Pioneers of Scientific Cookery." Good Housekeeping, Vol. 51, no.4, (October, 1910), p.472.

Moskin, Julia. “Overlooked No More: Fannie Farmer, Modern Cookery’s Pioneer.” New York Times, June 13, 2018.

Rachman, Anne-Marie. “Farmer, Fannie Merritt, 1857-1915.” MSU Libraries Digital Repository. Accessed November 2024.

Schlesinger, Elizabeth Bancroft. Notable American Women, 1607-1950, Volume 1: A-F, edited by James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul Samuel Boyer. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971. 643-644.

Shapiro, Laura. Perfection Salad: Women and Cooking at the Turn of the Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986.