Nipmuc Sonksq, Engineer, Fashion designer, MA State Commissioner on Indian Affairs

By Mariana Brandman, Ph.D.

At different times, Zara Cisco Brough* worked as an electronics engineer, a drafter, a fashion designer, and a state commissioner, but she made her greatest impact as a respected and effective leader of the Hassanamisco Nipmuc band from 1959-1984.

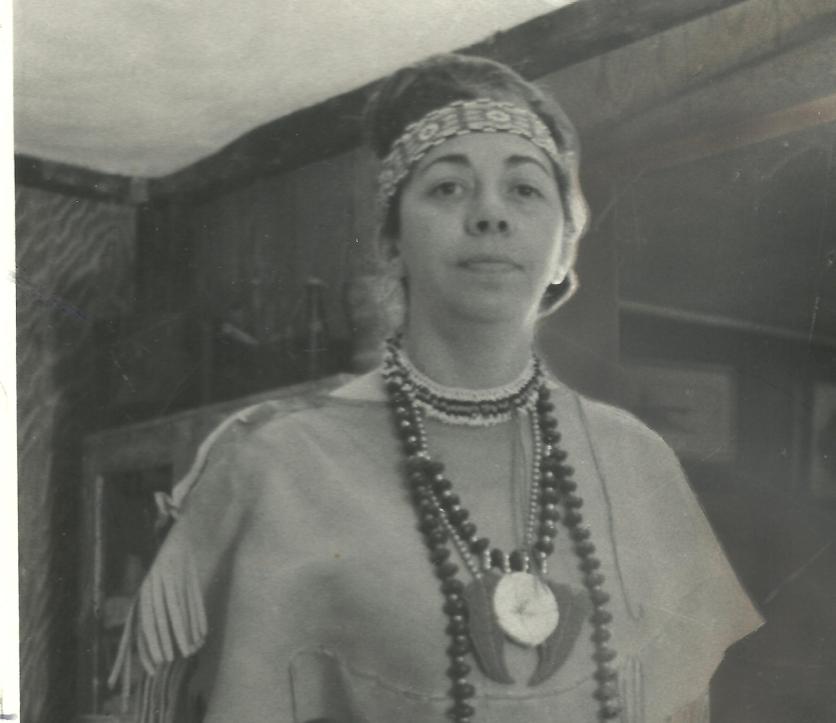

Zara Cisco Brough, also known as Princess White Flower, was born in New York City in 1919. She was the daughter of Sarah Cisco Sullivan and Charles Brough and she grew up on the Hassanamisco reservation (known as Hassanamesit) in Grafton, Massachusetts. The 3.5-acre reservation is what remains of the 7500 acres from the Nipmuc’s original 1728 land grant from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the even greater geographic area that the Nipmuc have inhabited since before written history. Cisco Brough came from a long line of Indigenous leaders: her great-grandfather Samuel C. Ciscoe was a Narragansett chieftain; her grandfather James Lemeul Cisco was a Nipmuc sachem, and her mother preceded her as Nipmuc sonksq (sonksq is the term for female leader of the tribe).

Cisco Brough studied engineering in college in Washington, D.C., and also studied at New York University. After NYU, she worked as a draftsperson and technical writer as well as a fashion designer. During World War II, she served as a civilian consultant to the United States Army Air Forces, earning the United States Air Force Award of Superior Performance.

In 1959, Cisco Brough returned to Grafton in order to care for her ailing mother. She became the vice president of Ibis Corp., an engineering consulting firm in Waltham, MA. That same year, she was named tribal sonskq and assumed leadership of the Hassanamisco Nipmuc band.

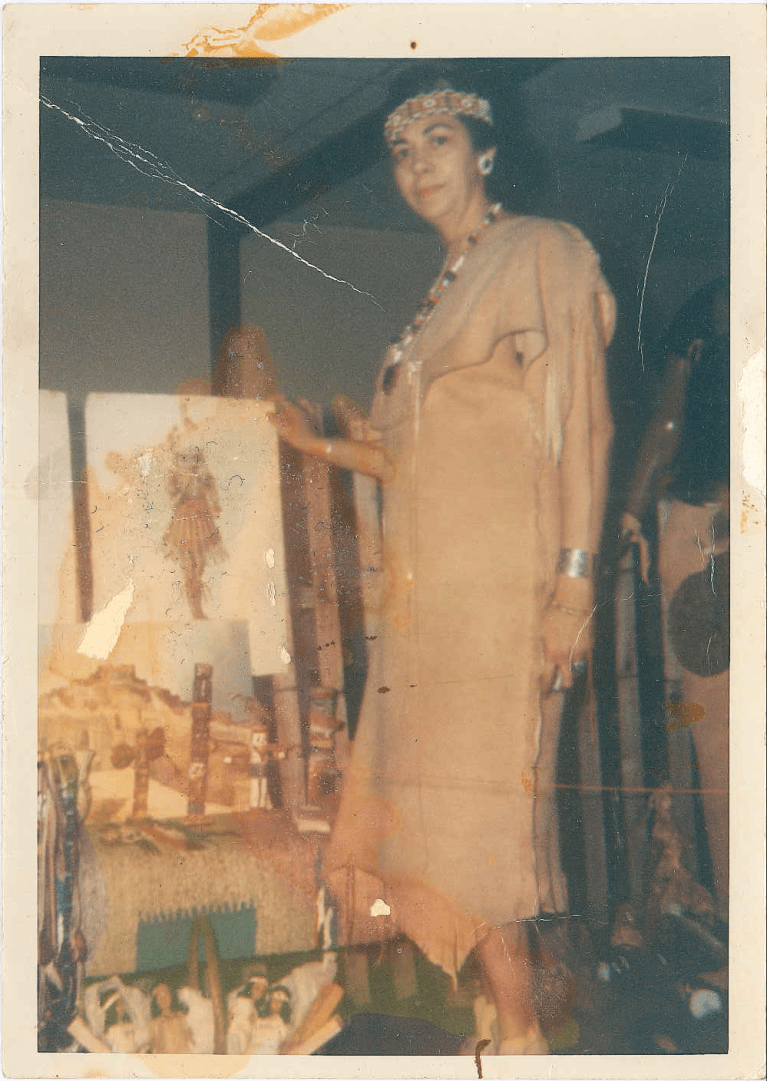

An important figure both as a businesswoman and a civic leader, Cisco Brough headed the Hassanamisco Nipmuc for 25 years. In 1962, she founded the Hassanamisco Indian Museum in order to preserve and promote Nipmuc history and culture. It was made up of two buildings: the nineteenth-century Homestead and a longhouse built specifically to display the museum’s artifacts and exhibits. (The Homestead, which at the time served as living quarters for Nipmuc leadership, is the “oldest known frame dwelling continuously occupied by Native Americans in New England,” according to the Hassanamisco Indian Museum.) Also in 1962, Cisco Brough helped form the Hassanamisco Foundation, in order to keep the Homestead and reservation lands in Nipmuc hands.

Cisco Brough helped establish the Massachusetts Commission of Indian Affairs and served as its first Nipmuc commissioner from 1974 to 1984. Cisco Brough also won an important victory for the Nipmuc when she secured their dredging rights to nearby Lake Ripple.

Under Cisco Brough’s leadership, the Nipmuc were recognized at the state level by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1976. State-level recognition brings advantages, such as access to state government services and benefits. Federal recognition (meaning the U.S. government acknowledges a government-to-government relationship with the tribe) requires Native tribes to meet other specific criteria and affords them certain rights to self-government as well as federal benefits and services. Cisco Brough also oversaw a petition for federal recognition of Nipmuc nation, but that ultimately unsuccessful effort was not resolved until 2004, long after her tenure as sonskq and after she had passed away.

As one of her many efforts to preserve Indigenous cultural heritage, Cisco Brough created and collected a variety of Northeastern Indigenous recipes between 1977 and 1983. In 2009, the Nipmuc Nation Elders Council published the cookbook, entitled Northeastern Native American Foods.

She passed away in 1988 in Westborough, Massachusetts. In 2009, the Massachusetts State Legislature officially named a Department of Youth Services Facility in Westborough the Zara Cisco Brough “Princess White Flower” Facility, in honor of Cisco Brough’s dedication to her community.

*The spelling of Cisco varies in historical records between Cisco and Ciscoe.

Additional Resources

Cisco Brough, Zara. Northeastern Native American Foods. 2009.

Bibliography

“About.” Hassanamisco Indian Museum.

“DEATHS ELSEWHERE.” Washington Post. Jan. 14, 1988.

Holley, Cheryll Toney. “A Brief Look at Nipmuc History.” Hassanamisco Indian Museum.

“House bill naming new Youth Services facility passes.” WickedLocal.com. Jan. 8, 2009.

Senier, Siobhan. ed. Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. United Kingdom: Nebraska, 2014.