Ground-Breaking Poet

By Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian

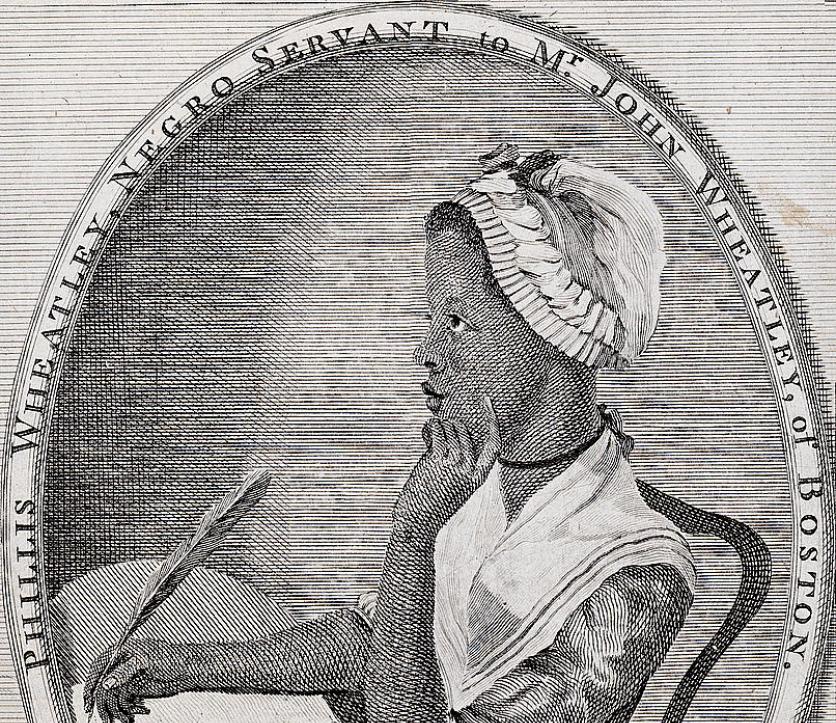

The woman known as Phillis Wheatley reached international acclaim with her poetry, becoming the first Black woman in the American colonies to publish a book.

In July 1761, a young girl kidnapped from her home in West Africa arrived in Boston on a slave ship. About seven years old, she was described as frail, likely from the rough voyage and trauma she had undergone. Boston merchant John Wheatley and his wife Susanna purchased the girl and named her after the ship she arrived on – Phillis.

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

–“To the Right Honourable William Earl of Dartmouth,” 1772.

While enslaved, Phillis received an uncommon education for her status. She quickly picked up English, and the Wheatleys, possibly Susanna or daughter Mary, taught her how to read and write. Phillis read the Bible, Greek and Latin classics, and British literature.

Phillis Wheatley wrote her first poems around age twelve or thirteen in about 1765. Soon after, local newspapers and journals began publishing some of her poems. In her poetry, Wheatley often wove in religious and classical themes. Many of her poems were elegies – poems honoring the deceased.

Her elegy of the Methodist evangelist Reverend George Whitefield in 1770 made her famous among the colonies. Despite her success, Wheatley could not garner support for publishing a book of poetry. Instead, she looked across the Atlantic. Traveling to London with Nathaniel Wheatley, the son of John and Susanna, Phillis Wheatley gained respect in London circles.

Through the Wheatleys’ connections, she received funding for her book from Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon. Wheatley’s book of poetry, Poems of Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published in London in 1773. Within the first pages of the piece, an attestation signed by notable Massachusetts leaders, including Governor Thomas Hutchinson and John Hancock, confirmed Phillis Wheatley’s authorship.

Recent scholarship acknowledges her books arrived in Boston via the trading ship Dartmouth, along with other goods and tea – the same tea that colonists dumped overboard into Boston Harbor during the infamous Boston Tea Party.

Around the same time of her book publication in 1773, Phillis Wheatley obtained her freedom. Some scholars have suggested that a recent ruling in London, one that determined any enslaved person from the colonies could claim freedom on England’s shores, prompted her freedom. It remains unclear whether Phillis Wheatley struck a deal with the Wheatleys to return to Boston under the condition of freedom, or whether the Wheatleys chose to free Phillis of their own accord. She still remained close to the Wheatley family during their lifetime.

Following the success of her book, little documentation remains as to the activity of Phillis Wheatley for the rest of her life. She met John Peters, a free Black man, and they married in 1778. They might have had as many as three children, though none survived to adulthood.

Phillis and John Peters struggled to make ends meet – Phillis could not garner support for the publication of a second book and eventually worked in a boarding house. John found himself in legal troubles, at one point landing in debtor’s prison.

Struggling financially and often in poor health, Phillis Wheatley Peters died on December 5, 1784 at the age of 31.

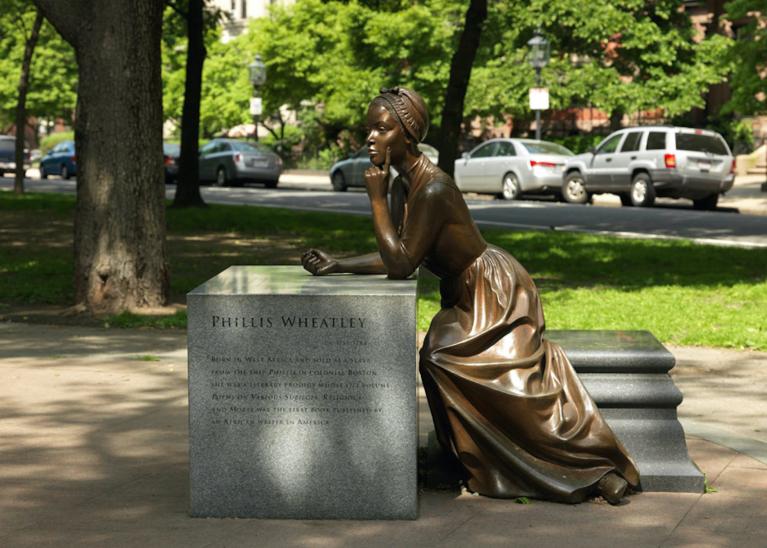

Although living a tragically short life, Phillis Wheatley’s poetry has kept her voice alive for over 200 years. She continues to have a presence in classrooms and other public spaces, including the Boston Women’s Memorial, which features her alongside Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone.

Additional Resources

brown, drea. “The Multiple Truths in the Works of the Enslaved Poet Phillis Wheatley.” Smithsonian Magazine. June 24, 2020.

“Phillis in Boston.” Revolutionary Spaces. Accessed December 2023.

“Phillis Wheatley.” African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts. Massachusetts Historical Society. Accessed December 2023.

Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. The Age of Phillis. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2020.

Waldstreicher, David. The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet's Journeys Through American Slavery and Independence. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023

Bibliography

Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2014.

Colby, Celina. “First edition Phillis Wheatley poetry book acquired by Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum.” Bay State Banner. December 13, 2023.

Michals, Debra. “Phillis Wheatley.” National Women’s History Museum. 2015. Accessed December 2023.

Moschella, Jay. “Tracing the Life of Phillis Wheatley Peters.” BPL Blogs. September 21, 2023.

O’Neale, Sondra A. “Phillis Wheatley.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed December 2023.

“Phillis Wheatley.” National Park Service. Last modified January 17, 2023.

“Phillis Wheatley’s poem on tyranny and slavery, 1772.” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed December 2023.

Sheridan, Stephanie. “Phillis Wheatley: Her Life, Poetry, and Legacy.” National Portrait Gallery. Accessed December 2023.

Winkler, Elizabeth. “How Phillis Wheatley was Recovered Through History.” The New York. July 30, 2020.