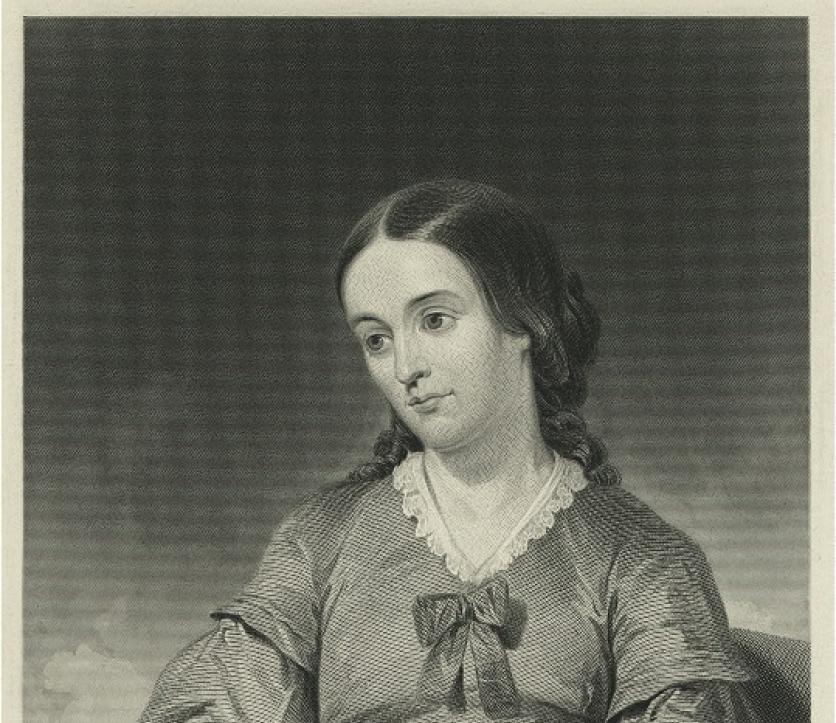

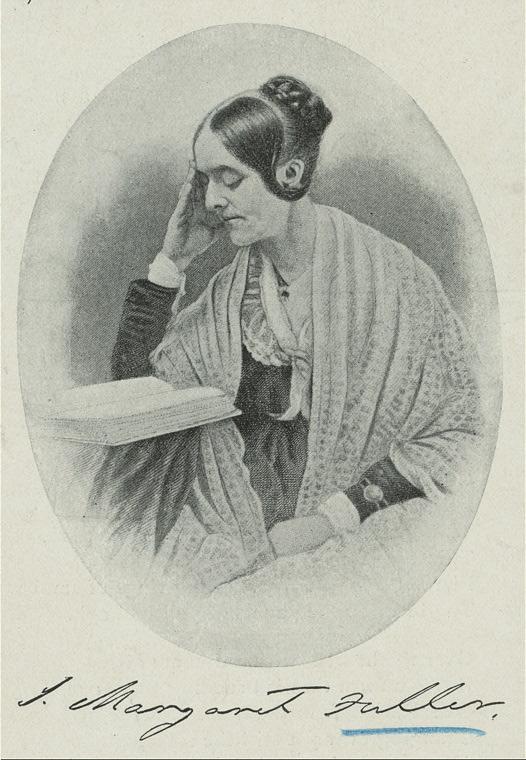

Writer, Editor, Journalist, and Women’s Rights Advocate

By Katie Woods, Digital Public Historian

Margaret Fuller not only gave voice to women’s potential, but she also exemplified it through her successful career as a ground-breaking journalist and writer.

Sarah Margaret Fuller was born on May 23, 1810, to parents Timothy Fuller and Margarett Crane Fuller in Cambridgeport. Because of her father’s position as a lawyer and state senator, Fuller received an education not often available to girls and young women at the time. She first took lessons at home under her father’s direction before attending school in Groton. Fuller became well-acquainted with the classical works, read books published by European authors and philosophers, and learned several languages, including Greek and Latin.

After her father’s untimely death in 1835, Fuller began teaching at Boston’s Temple School, run by Bronson Alcott (father of famed writer Louisa May Alcott). She subsequently spent two years teaching at the Greene Street School in Providence, RI.

In the late 1830s, Margaret Fuller befriended Ralph Waldo Emerson, a leader of the Transcendentalist movement. Fuller immersed herself in the circle of Transcendentalists in Concord, MA, which included friends Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and James Freeman Clarke One of a few women in this group, she became familiarized with the Transcendentalist values of self-reliance, idealism, individualism, and intellectual pursuit. Fuller, along with fellow Transcendentalist and educator Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, organized “Conversations” for Boston women to discuss these concepts and encourage intellectual curiosity among women.

Through this movement, Fuller’s literary career began to take shape. She edited the Transcendentalist quarterly journal The Dial for two years before moving to New York to serve as a writer and editor for the New York Tribune. Fuller became regarded as an accomplished writer, editor, and journalist. For the Tribune, she wrote columns on anything from literature and music to politics and social reform.

Perhaps Margaret Fuller is best known for her work Woman in the Nineteenth Century, published in 1845. Expanded from a tract previously published in The Dial as “Man versus Men, Woman versus Women,” this work is considered by many to be the first feminist work published in the United States. In this book, Fuller echoes transcendentalist concepts as she encourages a new awakening among women to see their possibilities.

What woman needs is not as a woman to act or rule, but as a nature to grow, as an intellect to discern, as a soul to live freely and unimpeded…"

- Margaret Fuller in Woman in the Nineteenth Century

In 1846, Fuller began a sojourn in Europe, reporting on her travels to the Tribune as one of the first female foreign correspondents. Making her way through England and France, she eventually landed in Rome. Over the following four years, Fuller continued to relay news of European happenings to the Tribune while also witnessing and documenting the events of the 1848 Italian Revolution.

While in Rome, Fuller met the Marquis Giovanni Angelo Ossoli, an Italian nobleman. Due to the couple’s secrecy, details of their relationship and possible marriage are uncertain, though Fuller gave birth to their son Angelo in late 1848. Fuller served as a superintendent of a Roman hospital while Ossoli defended the Republic as a soldier. With the failure of the Republic, they fled to Florence until they could secure passage to the United States. In 1850, the family sailed home aboard the Elizabeth, which tragically sank off the coast of Fire Island, New York. Fuller and her family all died in the shipwreck.

With her life tragically cut short, Fuller’s writings became her legacy. Julia Ward Howe said of Fuller, “As a woman who believed in women, her word is still an evangel of hope and inspiration to her sex.”

Bibliography

Fuller, Margaret, Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Henry Channing, and James Freeman Clarke. Memoirs of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, Vol 3. London: Richard Bentley, 1852. Accessed November 2023.

Fuller, S. Margaret. Woman in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Greeley & McElrath, 1845. Accessed November 2023.

Howe, Julia Ward. Margaret Fuller (Marchesa Ossoli). Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1883. Accessed November 2023.

“Margaret Fuller.” Poetry Foundation. Accessed November 2023.

Marshall, Megan. Margaret Fuller: A New American Life. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Reynolds, Kim. “Notable Women, Notable Manuscripts: Margaret Fuller.” Boston Public Library. February 28, 2019.