By Mariana Brandman, Ph.D.

In May 1969, a group of young women met at Boston’s Emmanuel College to attend a female liberation workshop called “Control of our Bodies.” Some were veterans of the student and anti-war movements of the 1960s and together they began, as one later put it, “to shift our focus from these events to ourselves as women. For the first time, we began discussing our health, our work, our medical care.” While their numbers may have been small, the shift in their thinking – to center their bodies and their lived experience – was monumental. What began as an informal meeting in a single Boston classroom sparked a global movement that revolutionized how we think about women, health, and sexuality.

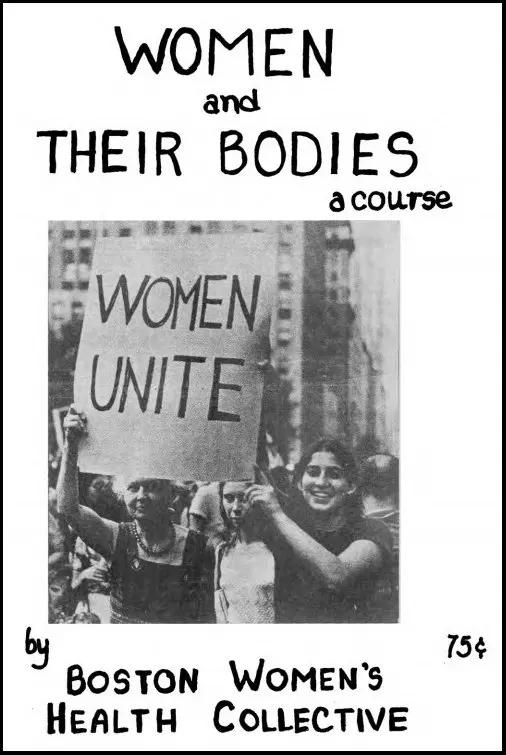

By 1969, the growing women’s liberation movement was working to dismantle many of the inequities that women faced in society, but much of the attention remained centered on legal and economic issues, rather than medical ones (even though the three often overlapped). Through their conversations, the workshop attendees recognized their shared frustration at how little they knew about their own bodies and their mistreatment at the hands of the (largely male) medical establishment. It inspired the group to continue meeting and to teach themselves about the inner workings of women’s bodies and how best to care for them. They convened throughout the summer to share their newfound knowledge, adding participants along the way. The following autumn they met weekly at MIT, where they held a ten-session “course” called “Women and Their Bodies” in order to help other women educate themselves about their bodies.

At each meeting, participants told stories of their encounters with the medical system and presented their own research on health issues they considered pressing, stigmatized, or neglected, such as abortion, birth control, and female sexual pleasure. Highlighting such topics meant taking a bold stance: at the time, abortion was illegal in much of the country, including in Massachusetts, and the Commonwealth prohibited contraception (and even information about contraception) for any individuals who weren’t married. (You can learn more about the surprising history of reproductive rights in Massachusetts here.) But, as the course organizers would soon learn, the demand for this information was high. Despite advertising only by word-of-mouth on the male-dominated MIT campus, the first session drew a crowd of almost 50 women. Participants recounted: “We met in the greater Boston area to talk about our lives, including reproductive health and sexuality concerns that we had never before discussed publicly.” In the process, they realized that “we knew as much about ourselves as our doctors did – in fact, often we knew more.”

They Set Out to Write One

Energized by their rewarding experience with the course, the group decided to make the information they had collected accessible to other women, initially as mimeographed papers available at many local workshops. Ultimately, because there were no books available at the time that addressed women’s health from a feminist perspective, they set out to write one. They convinced the New England Free Press to publish Women and Their Bodies in December 1970 and the stapled newsprint booklet first sold for 75 cents per copy. The coursebook included chapters on venereal disease, postpartum problems, and one intended to debunk “Some Myths About Women.”

The initial New England Free Press printing of 5,000 copies quickly sold out, but that was just the beginning. Little did these women know that their 193-page newsprint booklet would give rise to nine editions, almost three dozen foreign language adaptations, and more than four million copies in print. The book would come to be hailed as “the bible of women’s health."

A Growing Readership, A More Diverse Authorship

In 1971, with subsequent reprintings, the book title changed to Our Bodies, Ourselves (“to emphasize women taking full ownership of their bodies”). Despite little publicity, Our Bodies, Ourselves soon sold a quarter of a million copies.

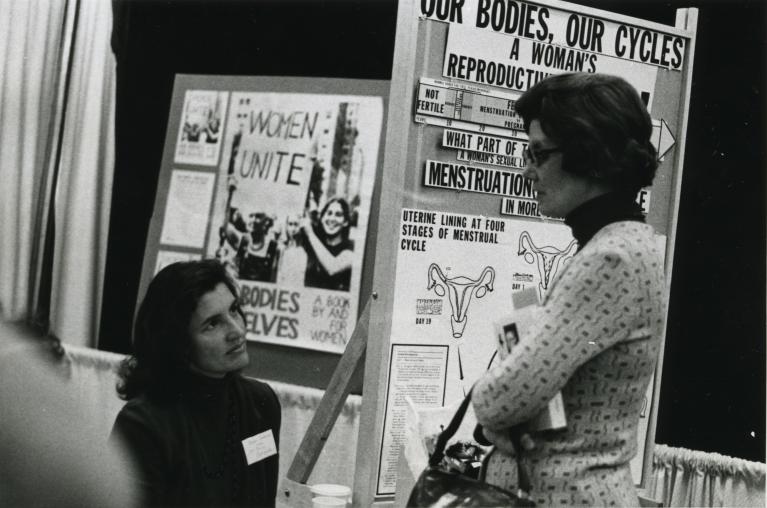

The group, which incorporated in early 1972 as the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (BWHBC), sought to provide a model for other women to educate themselves, communicate more effectively with their doctors, and challenge the health care system to improve medical care for women. They stressed that the process of coming together to share their experiences and empower each other was just as important as the content printed in their book. In the introduction, they wrote: “It was exciting to learn new facts about our bodies, but it was even more exciting to talk about how we felt about our bodies, how we felt about ourselves, how we could become more autonomous human beings."

In order to reach a wider audience, the BWHBC decided to publish with Simon & Schuster and the first commercial version of Our Bodies, Ourselves appeared in 1973. Early on, the group committed to donating its royalty earnings to grassroots women’s health initiatives. The BWHBC negotiated its contract with Simon & Schuster to include a special discount on clinic copies in order to make the book available to low-income women. The BWHBC also secured funds for the production of a Spanish language version of the book. Notably, the 1973 edition featured a chapter written by Boston-area lesbians, “In America, They Call Us Dykes,” which affirmed and celebrated homosexuality.

The early editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves primarily reflected the perspectives of the mostly white and college-educated women who first worked on it. Over time, the BWHBC diversified its contributors in order to better address topics such as racial disparities in healthcare, environmental and occupational health concerns, menopause, infertility, and disabilities. Internationally, women’s groups in over 30 other countries partnered with the BWHBC to adapt the content of Our Bodies, Ourselves to their cultures and political contexts, rather than merely translating the language of the text.

For many years, Our Bodies, Ourselves (or OBOS, as the organization is now called) operated on a small budget as they continued to funnel much of their royalties to women’s health initiatives while also refusing revenue from advertising or the pharmaceutical industry. But that didn’t stop OBOS from advocating vigorously on behalf of women’s health causes. Together with women both in the U.S. and abroad, OBOS worked to end forced sterilization, called for better safety information about the birth control pill and menstrual products, sought to improve breast cancer treatment methods, and advocated for safer practices in assisted reproduction.

Our Bodies Ourselves Today

OBOS published the ninth (and most recent) edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves in 2011. The following year, the Library of Congress included Our Bodies, Ourselves in the exhibition, “Books That Shaped America,” naming it one of 88 books that has had “a profound effect on American life.” OBOS continues to focus on women’s health advocacy in the U.S. and supporting its partner organizations across the globe. Meanwhile, the BWHBC’s stapled newsprint handbook lives on in digital form: Our Bodies Ourselves Today, a project of Suffolk University’s Center for Women’s Health and Human Rights, provides a rich online collection of resources on health and sexuality for women and gender-expansive people.

Our Bodies, Ourselves Founders & Key Figures:

- Ruth Davidson Bell Alexander

- Pamela Berger

- Ayesha Chatterjee

- Vilunya Diskin

- Joan Ditzion

- Paula Doress-Worters

- Nancy Miriam Hawley

- Elizabeth MacMahon-Herrera

- Pamela Morgan (1949-2008)

- Judy Norsigian

- Jamie Penney

- Jane Kates Pincus

- Esther Rome (1945-1995)

- Wendy Sanford

- Mary Stern

- Norma Swenson

- Sally Whelan

- Kiki Zeldes

Related News

Suffrage100MA | Women’s Equality Day 2023

Theme: Women’s Health & Maternal Health Crisis of Women of Color

Bibliography

MWHC thanks Judy Norsigian (Our Bodies Ourselves, Co-Founder and Board Member) and Laura Prieto, Ph.D. (Our Bodies Ourselves Today, Program Director) for their assistance with this article.

Boston Women's Health Book Collective Records, 1905-2003. MC 503. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Nicholson, Marjorie. “We Sparked a Women’s Health Movement by Speaking and Listening to the Truth.” Our Bodies Ourselves Today (blog), November 24, 2015.

Our Bodies Ourselves Today. “The History & Legacy of Our Bodies Ourselves.”

Our Bodies Ourselves Today. “OBOS Timeline: 1969-Present.”

Pincus, Jane. “How a Group of Friends Transformed Women’s Health.” Women’s eNews. March 13, 2002.

Stephenson, Heather and Kiki Zeldes. “‘Write a Chapter and Change the World.’ How the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective Transformed Women’s Health Then—and Now.” American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 10 (October 2008): 1741–45.