By Mariana Brandman, Ph.D.

“If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

The Combahee River Collective (CRC) – an organization of Black women in Boston, most of whom openly identified as lesbians – made this bold declaration in their 1977 manifesto, “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” The statement explained their political analysis that targeted the interlocking forms of oppression they faced as queer Black women: racism, sexism, homophobia, and capitalism. The CRC disbanded in 1980, but the group had a profound impact that resonates to the present day: they introduced the concept of identity politics and demonstrated how their lived experiences as Black women informed their revolutionary approach to social justice.

“The Smart Girl Crew” Mobilizes

In the 1960s and early 1970s, many CRC members had taken part in the male-dominated Civil Rights and Black nationalist movements and the predominately white women’s movement, but they felt overlooked and excluded by both groups because of their gender and race, respectively. Not only did they want to call attention to the specific challenges they faced as Black women, they also sought to shed light on the damage caused by capitalism and to align themselves with anti-colonial movements across the globe.

In 1974, sisters Barbara and Beverly Smith and Demita Frazier founded the CRC. Initially, Barbara Smith and Frazier brought together a group of Boston-area women who broadly aligned themselves with the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). Soon, however, the pair found that their priorities – opposition to capitalism and a non-hierarchical group structure – set them apart from many in NBFO. They broke off to create their own organization with Beverly Smith and called themselves the Combahee River Collective. They chose the name to honor and draw inspiration from Harriet Tubman’s 1863 Combahee River raid, the first major military operation in U.S. history planned and led by a woman. During the raid, Tubman commanded 150 Black Union troops and freed more than 700 enslaved persons in South Carolina. (On Veterans’ Day in 2024, Tubman was posthumously awarded the rank of one-star brigadier general in the Maryland National Guard for her leadership.)

The CRC’s membership fluctuated over the years, but the group’s core included intellectuals and activists such as Margo Okazawa-Rey and Chirlane McCray, along with the Smith sisters and Frazier. Prominent figures such as Audre Lorde, Akasha Hull, and Cheryl Clarke also had close ties to the group. The CRC met in Frazier’s Dorchester home and Barbara Smith’s residence in the South End before deciding to meet regularly at the Cambridge Women’s Center.

Calling themselves “the smart girl crew,” they read Black literature, engaged in consciousness-raising discussions, and theorized their revolutionary political vision. They took pride in the intellectual interests that had at times earned them mockery from the men in their lives. Together they fostered a vibrant sense of community and forged cherished friendships. The CRC’s lively gatherings often included elaborate meals, astrological readings, and reenactments of the latest sketches from Saturday Night Live.

Individually and collectively, CRC members worked on issues such as domestic violence, sexual assault, police brutality, school desegregation, health care, and reproductive justice. (While many white women in the women’s movement focused on and fought for abortion rights, women of color often expanded the concept to one of reproductive justice, including the right to have children, knowing they were much more likely to experience coerced sterilization at the hands of the medical establishment. The right to abortion was only one part of the reproductive autonomy that feminists of color sought to achieve.)

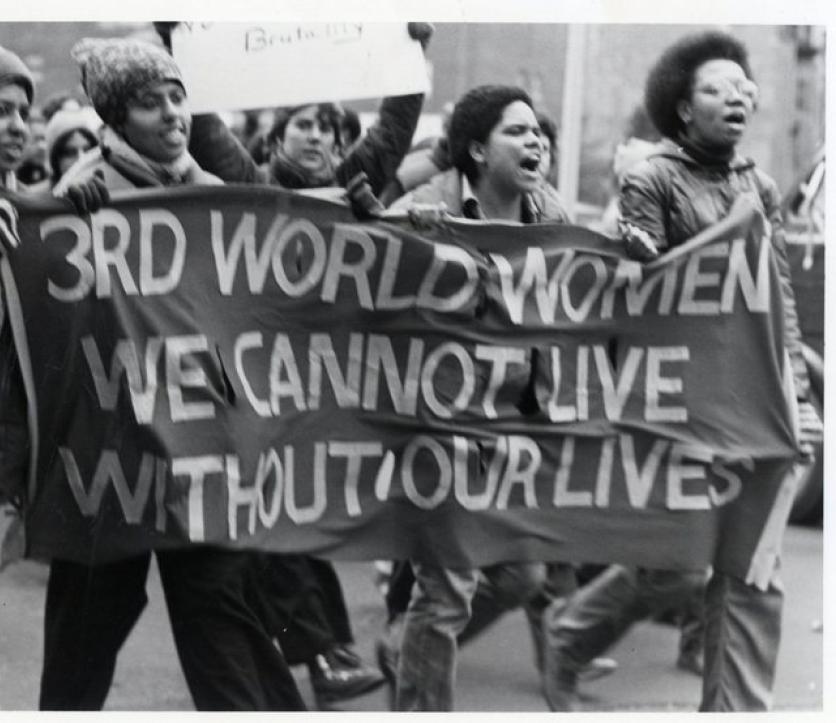

In 1979, when 11 Black women and one white woman in Boston were found murdered in the span of five months, the CRC mobilized to raise public awareness of the crimes. They called on the police and the media to acknowledge the racial, gender, and class dimensions to the attacks. The CRC also produced a pamphlet that explained the social and political factors behind the crimes and provided safety information for women of color. On April 28, 1979, together with other local progressive groups, they organized a 500-person march against racialized and sexualized violence on the Boston Common.

The Combahee River Collective Statement

In April 1977, the CRC issued “The Combahee River Collective Statement.” The essay explained their intention to “develop a politics that was anti-racist, unlike those of white women, and anti-sexist, unlike those of Black and white men.” It also expressed their view that Black feminism constituted “the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face.”

The statement emphasized the interconnected nature of racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, declaring: “The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives.” The CRC felt that it was crucial to reckon with the confluence of these forces: any revolution that failed to address all of these factors would ultimately fall short for Black women.

Today, we more commonly refer to this multidimensional perspective as “intersectionality.” Law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw first coined the term in 1989. Her legal analysis, which demonstrated how different identity categories intersect with each other in ways that can lead to social inequality, built on the scholarship of critical race theory and the conceptual work of Black feminists, including the Combahee River Collective.

In their analysis, the CRC situated themselves in a long history of Black women who drew on multiple aspects of their identities in their fight for survival and liberation, including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, Frances E.W. Harper, Mary Church Terrell, and “thousands upon thousands unknown.” The strong bonds they forged with each other also influenced their outlook. They wrote, “Our politics evolve from a healthy love for ourselves, our sisters and our community which allows us to continue our struggle and work.” It was here that they introduced the term “identity politics,” explaining their view that “the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity.”

The phrase “identity politics” has elicited a fierce backlash in recent years, as people across the political spectrum have interpreted it in many different ways in order to advance their own agendas. However, in 2021, Barbara Smith clarified what the CRC intended the phrase to mean in their 1977 statement and why it mattered: “Black women have a right to create a political agenda based on our intersecting identities. And why was that so important at the time? No one else believed it.”

The Combahee River Collective Statement detailed how identity politics informed their perspectives on issues of class and sexuality. The CRC acknowledged their general agreement with Marxism, but called for a recognition of “the real class situation of persons who are not merely raceless, sexless workers,” claiming that such analysis “must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.”

Similarly, the CRC took pride in their lesbian identities, but rejected the separatism that a number of lesbians embraced in the 1970s. While they condemned the sexism they often encountered from men, the CRC refused to exclude them simply for being male, claiming that biological determinism was a dangerous foundation for a new political vision. They also criticized some lesbian separatists for denying class and race as sources of oppression for Black women.

Combahee’s Legacy

“The Combahee River Collective Statement” was first published in Capitalist Patriarchy and the Case for Socialist Feminism (1978), an anthology intended for an academic readership. However, the statement has since reached much wider audiences due to its seven short pages of clear and powerful language. In the past five decades, many teachers have included it in women’s and gender studies courses, and today it is regarded as a foundational text of Black feminism. Contemporary social justice movements like Black Lives Matter credit the Combahee River Collective’s political vision as an inspiration for their work.

The CRC disbanded in 1980. Members say there was no internal fight or schism, simply that it reached a natural end as everyone’s lives took them in different directions. However, the racial and class tensions that permeated Boston in the late 1970s and early 1980s also played a role. The atmosphere of violence and anger – brought to the fore during the busing crisis several years earlier – made it difficult for the CRC to continue organizing, despite the strong coalitions they had built with other progressive organizations in the city.

Members of the CRC went on to distinguished careers as writers and poets, academics, and transnational political activists. Notably, Barbara Smith and Audre Lorde helped to establish Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press in 1981. Kitchen Table published works by and for women of color and is best known for publishing the second edition of Chicana activists Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s anthology, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (1983).

Fifty years after its founding, the legacy of the Combahee River Collective extends far beyond Boston. Though controversial to some, identity politics and intersectionality are nonetheless key concepts in contemporary US politics. The social revolution the Combahee River Collective sought remains unfinished, but new generations of activists continue to draw on the CRC’s pioneering political analysis to create their own agendas to bring about a more just and equitable future.

Additional Resources

“(1977) The Combahee River Collective Statement.” BlackPast. November 16, 2012.

Akasha Gloria Hull, Patricia Bell-Scott, and Barbara Smith. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women's Studies. Old Westbury, N.Y.: Feminist Press, 1982.

Edda L. Fields-Black. Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom During the Civil War. United States: Oxford University Press, 2024.

Christa Kuljian. Our Science, Ourselves: How Gender, Race, and Social Movements Shaped the Study of Science. United States: University of Massachusetts Press, 2024.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Barbara Smith, Beverly Smith, Demita Frazier, Alicia Garza, and Barbara Ransby. How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2017.

Works Cited

Special thanks to Beverly Smith for her contributions.

“(1977) The Combahee River Collective Statement.” BlackPast. November 16, 2012.

“Center for Intersectionality and Social Policy Studies Established.” Columbia Law School. October 12, 2011.

Coaston, Jane. “The Intersectionality Wars.” Vox. May 28, 2019.

Daniels, Cheyanne M. “Abolitionist Harriet Tubman Posthumously Awarded Rank of General.” The Hill (blog), November 12, 2024.

Fleischmann, Susan. “Members of Combahee River Collective at the March and Rally for Bellana Borde against Police Brutality (Boston, January 15, 1980).” The History Project | Documenting LGBTQ Boston.

Gray, Ariell. “This Boston Collective Laid The Groundwork For Intersectional Black Feminism,” WBUR. June 10, 2019.

Jackson, Ashawnta. “How Kitchen Table Press Changed Publishing.” JSTOR Daily. March 27, 2021.

Jones, Marian. “‘If Black Women Were Free’: An Oral History of the Combahee River Collective.” The Nation. October 29, 2021.

Taylor, Keeanga-Yamahtta. “Until Black Women Are Free, None of Us Will Be Free.” The New Yorker. July 20, 2020.

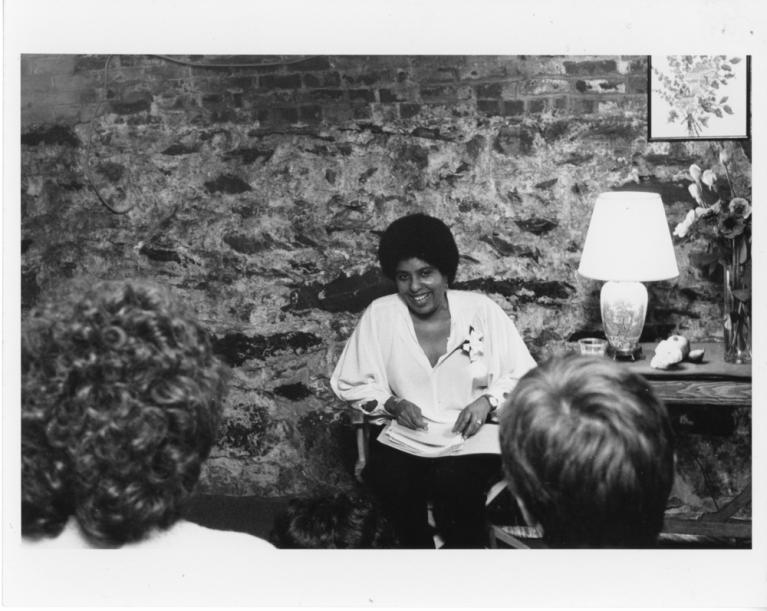

Unknown. “Barbara Smith, Sesquicentennial Award,” The History Project | Documenting LGBTQ Boston.

Wedule, N. “Beverly Smith at New Words,” The History Project | Documenting LGBTQ Boston.