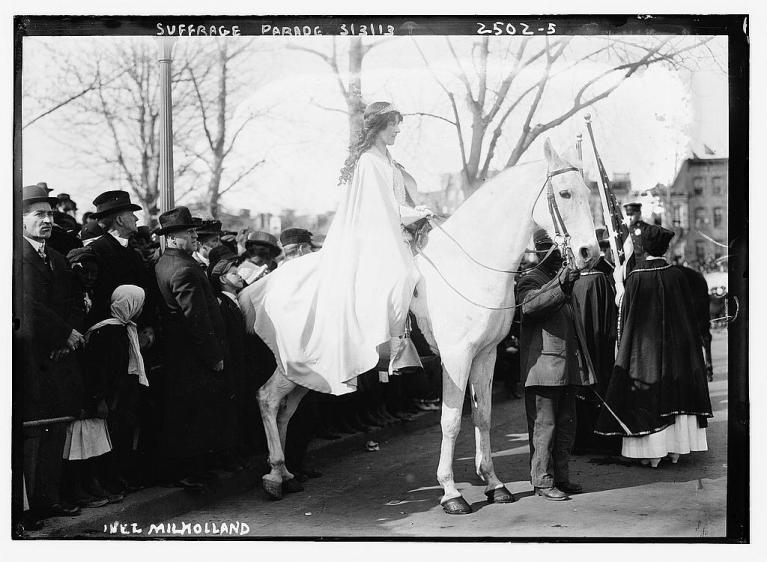

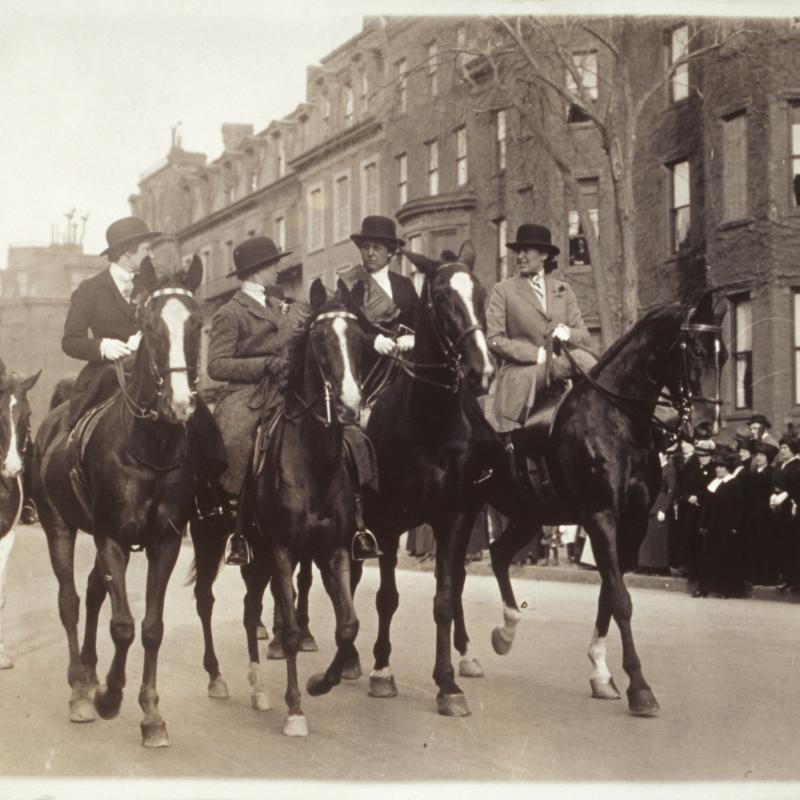

Inez Milholland at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Introduction

In 1776, the same year the United States declared its independence from Great Britain, Weymouth native Abigail Adams famously implored her husband, John Adams, to “remember the ladies.” She urged her husband, a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress, to include women in the new republic’s political system, reminding him: “If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” John Adams dismissed his wife’s plea, but the rebellion she foresaw came to be: the women's suffrage movement. Suffragists fought for nearly a century against the hypocrisy of living under laws in which they had no say.

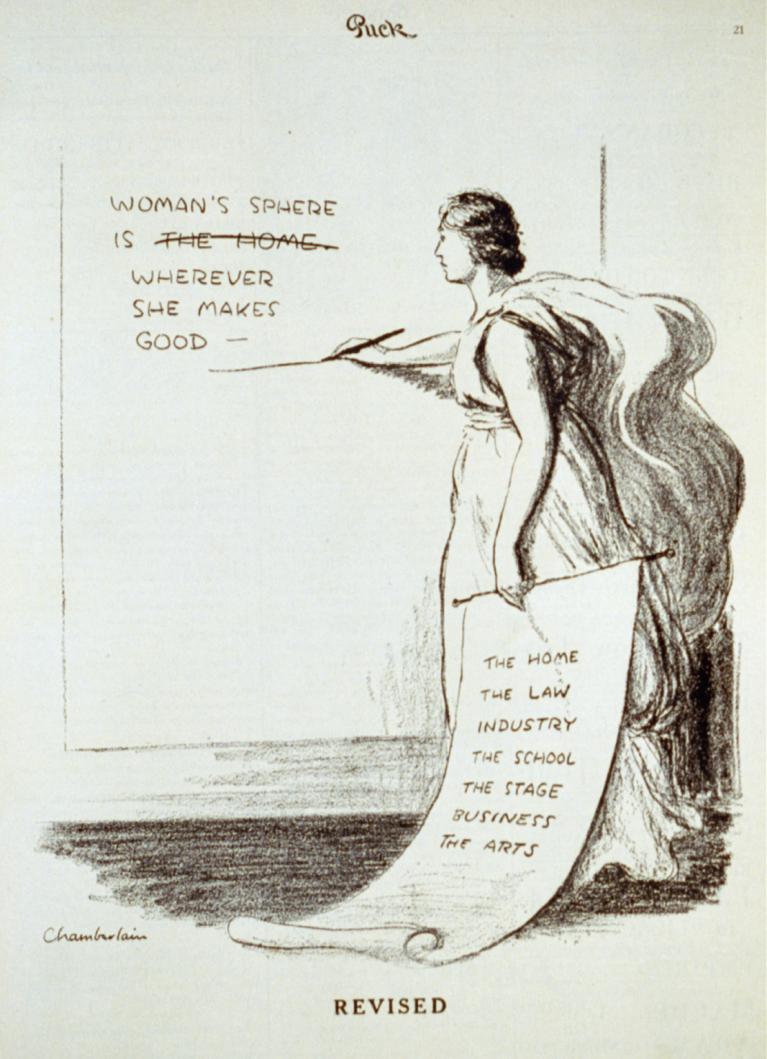

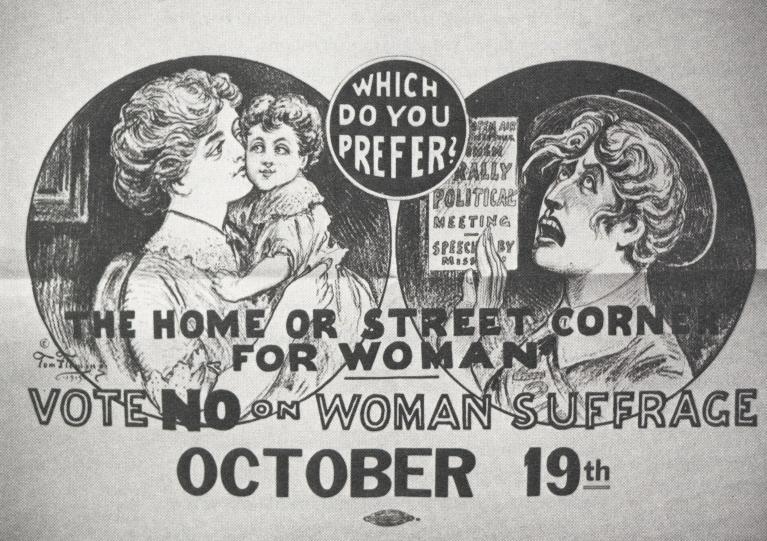

Before 1920, it was perfectly legal for the government to prohibit women from voting simply because of their gender. Restricting voting rights to men made sense to those who felt that society was properly divided into two spheres: the public sphere for men and the private sphere for women. Men were supposed to leave the home each day to go to work, take part in higher education, participate in running the government, or make their mark on the world in myriad other ways, while women were to remain at home to cook and clean and care for the children.

At the time of the country’s founding, it was commonly understood that men were the head of the household and therefore voted on behalf of the entire family. In fact, married women had very few legal rights in the nation’s early years: for example, they could not own property, testify in court, or divorce their husbands.

The women’s rights movement arose in the mid-19th century, as a growing number of women became dissatisfied with their lack of power–legal, social or otherwise–to determine their own destinies. They sought to expand opportunities and improve conditions for their fellow women and soon focused on the right to vote. They came to view suffrage as the key that would unlock the rest of the doors that were closed to women.

Zooming In on Massachusetts

Question: How did Massachusetts suffragists help make women’s right to vote the law of the land in the United States?

Together, suffragists created a nationwide movement that fought a 70+ year battle to break down gender discrimination in voting laws, and Massachusetts women played central roles all along the way. Their innovative political strategies and determined organizing offer a window into the historic effort to enfranchise American women.

Not only was Massachusetts the site of the first-ever national woman’s rights convention in 1850 (following the smaller and more regional Woman’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, NY 1848), as well as the birthplace of the anti-suffrage movement, but Commonwealth suffragists also experienced triumphs and setbacks that mirrored the broader campaign taking place all across the country.

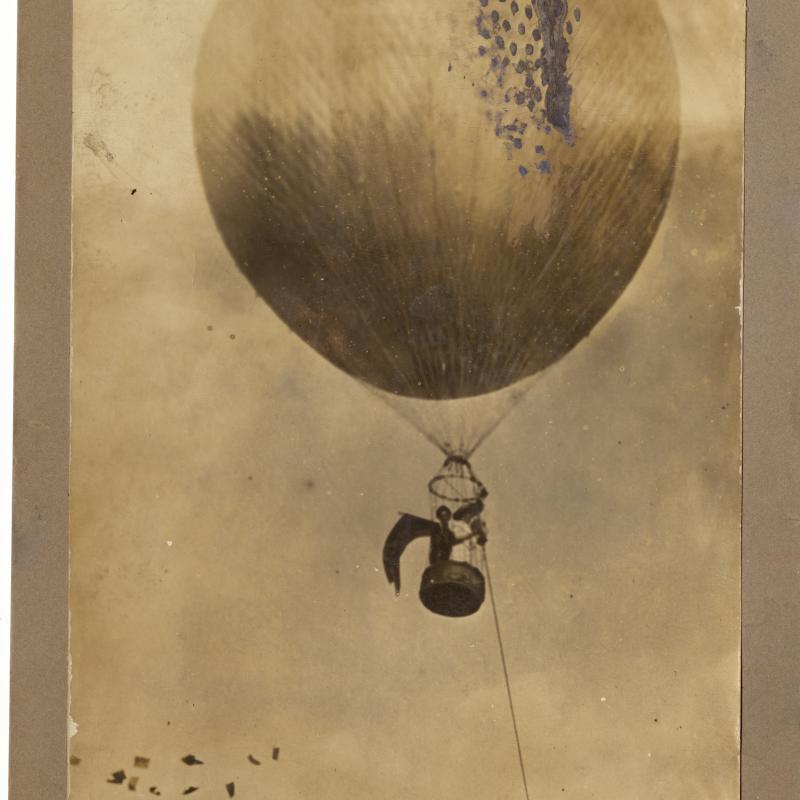

Massachusetts suffragists pioneered new strategies and used a range of diverse tactics to secure the vote for women. They developed sophisticated strategies to lobby the government, craft their image in the media, and persuade people from all walks of life about the benefits of votes for women. Their tactics (how they executed their strategies) featured everything from holding conventions and publishing pro-suffrage newspapers to staging suffrage pageants and fundraising bazaars – they even traveled the state by hot air balloon to spread the suffrage message!

Bay state suffragists drew on political tools that were common during their time and adapted to the rapidly changing society in which they lived, coming up with new ideas about how to win over their opposition and bring about the single greatest expansion of voting rights in the nation’s history.

Why Suffrage History Matters Today

Suffragists became savvy political operators during the seven decades it took to strike down voting restrictions on the basis of sex. In this exhibit, we’ll see how their persistence and ingenuity led to the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which guaranteed that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged…on account of sex.”

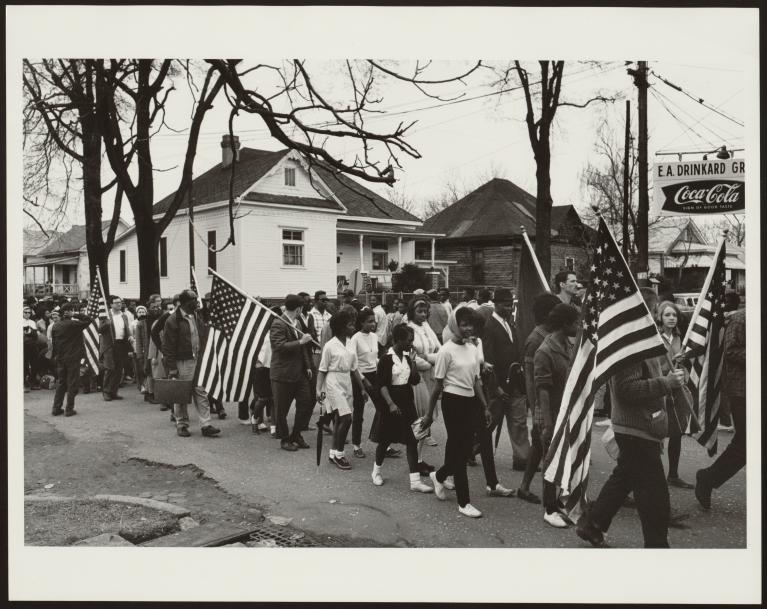

However, the fight for equal voting rights did not end in 1920. Even though the 19th Amendment does not discriminate, many women – and men – continued to be disenfranchised by other laws denying citizenship and/or the vote to people of certain races or ethnicities. Native Americans were largely prevented from voting until the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, and their suffrage rights were not achieved nationwide until 1957, when Utah became the last state to remove formal barriers. In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act made it legal for Asian immigrants to become citizens and vote. African Americans in the South were consistently denied the ballot until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Additionally, non-English speakers have faced difficulty voting because of language barriers and individuals with disabilities have had to fight to ensure the availability of accessible voting methods.

Threats and barriers to voting rights persist nationally to this day, so we have to continue the fight to protect voting rights. Examining the history of the women’s suffrage campaign in Massachusetts can inspire us, offer lessons for defending and ensuring voting rights today, and remind us just how important it is to make all our voices heard.

Civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

The Organizing Begins

The usual story of the women’s rights movement and the organized suffrage movement begins in 1848 with the first Woman's Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. But important events in this early history took place in Massachusetts.

Separate Spheres

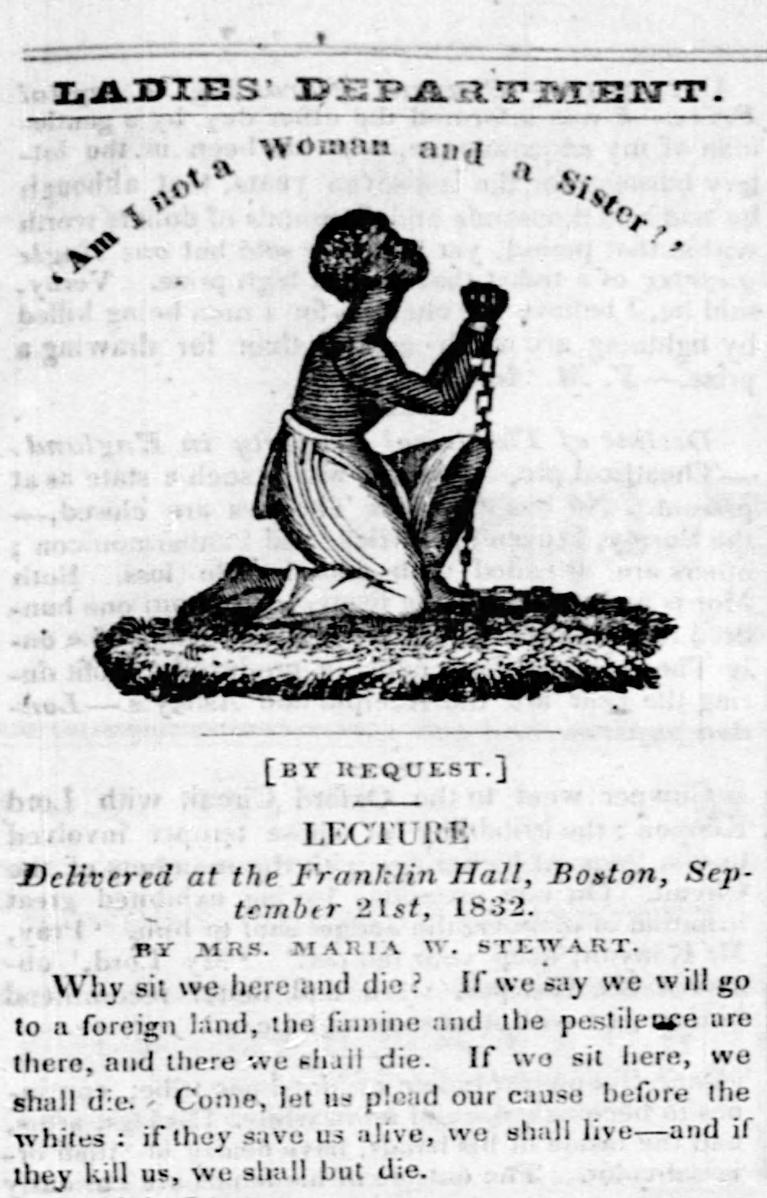

The prevailing notion of separate spheres for each gender – the home for women and the public for men – meant that in the early to mid-19th century, it was unheard of for women to speak in front of public audiences. Public speaking was the domain of men, just like voting. But women were increasingly getting involved in matters that took them outside the home, such as religion and abolition.

It’s important to remember that this stark divide between the public and private applied much differently to men and women of color than to white men and women in the early 19th century. The reality of slavery and racial prejudice meant that African Americans of both genders had fewer rights and opportunities than white Americans, and that Black women had the burden and legal limitations of being both female and Black. The injustices of sexism and racism were interrelated. As a result, the abolition movement and the women’s suffrage movement were closely aligned in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Abolitionist Origins

On September 21, 1832, Maria Stewart gave an address before a crowd of men and women at Franklin Hall, the meeting place of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. A freeborn Black woman, Stewart taught herself to read as a child and became active in the abolition movement, publishing many antislavery pieces in William Lloyd Garrison’s Boston-based newspaper, The Liberator. Her speech at Franklin Hall was one of the first recorded instances of an American woman speaking before a mixed-gender audience. She condemned slavery in the South as well as racial prejudice in the North, and advocated for greater educational and occupational opportunities for Black women. For daring to speak before a “promiscuous” (mixed-gender) crowd, Stewart received significant backlash from the public.

“American women have to do with this subject, not only because it is moral and religious, but because it is political.”

Angelina Grimké, 1838

The Grimké Sisters

Angelina and Sarah Grimké were white sisters who grew up on their father’s plantation in South Carolina, where they witnessed the cruelty of slavery firsthand. When they were young adults, they spent time in Philadelphia where they were influenced by Quakerism and came to see slavery as a moral sin that had to be abolished. Like many women of their time, abolition activism led them to join the fight for women’s rights.

In 1837, working with the American Anti-Slavery Society, the Grimké sisters embarked on a speaking tour of Massachusetts to share their firsthand accounts about the cruelties they had witnessed on their father’s South Carolina plantation. They visited 67 towns across the Commonwealth, reaching over 40,000 people by some estimates.

Many of their contemporaries were scandalized by the idea of women speaking publicly on political issues. The sisters encountered angry mobs on their tour and were condemned by clergy who claimed they were responsible for “permanent injury” to womankind. But the Grimkés persisted.

Question: Why do you think people were angry at the Grimkés for exercising their right to speak publicly?

Over two days in February 1838, Angelina spoke at the Massachusetts State House to “an overflow crowd of five hundred” including “supporters, detractors, and the merely curious.” It was the first time in the country that a woman had addressed a legislature and she and her sister, Sarah, had come to deliver 20,000 signatures they had collected from women opposing slavery. Angelina defended her right to address the legislature on the matter of slavery, claiming that "American women have to do with this subject, not only because it is moral and religious, but because it is political."

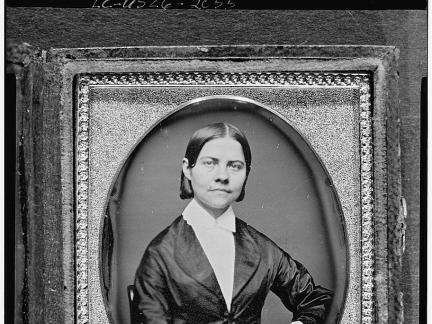

Lucy Stone

Nine years later, in 1847, Massachusetts native Lucy Stone gave the first set of lectures dedicated to, in her words, the “elevation of her sex.” The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, founded by prominent abolitionist and newspaper publisher William Lloyd Garrison, sponsored her speaking tour. When fellow anti-slavery advocates criticized Stone’s inclusion of women’s rights, she replied: “I was a woman before I was an abolitionist.” Stone refused to give up the cause and renegotiated her arrangement with the Anti-Slavery Society to deliver abolition lectures on weekends and women’s rights lectures on weekdays. Her efforts demonstrate yet another connection between the abolition movement and the nascent women’s rights movement.

That same year, Stone had graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio. Oberlin was the only college in the nation to admit women at the time and Stone became the first Massachusetts woman to graduate from college. The extent of the prohibition for women to speak in public was further illustrated when Oberlin officials asked Stone to draft a commencement address for her graduation ceremony, but insisted that a man deliver the remarks instead of her. When she learned the terms, she refused to write the speech.

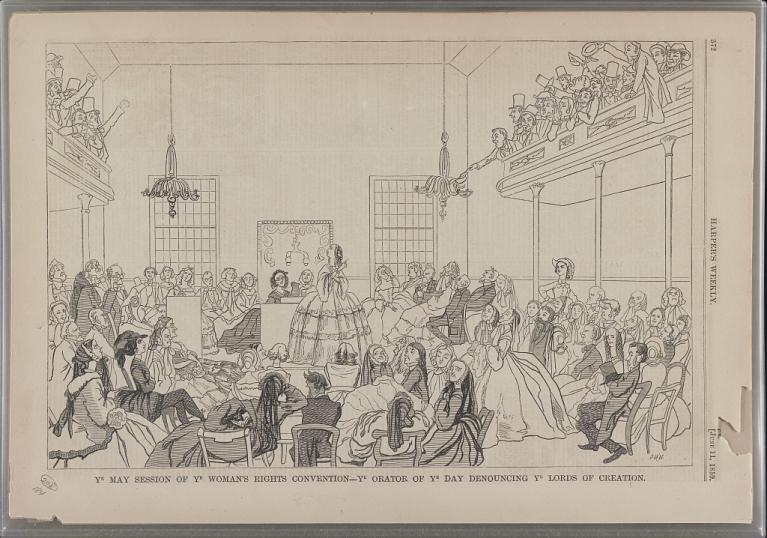

The First National Women’s Rights Conventions

In 1850, two years after the Seneca Falls convention, Stone and other Massachusetts-based activists held the first National Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester. Whereas Seneca Falls was a regional gathering, the Worcester convention drew more than 1,000 delegates from 11 states. They met in Brinley Hall and called for women’s rights to vote, own property, attend college, and enter professions such as medicine and the ministry. They returned to Worcester a year later for the Second National Women’s Right Convention, and continued to meet annually for a decade in different cities until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861.

Lectures and conventions were common political tools of the era (such as the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787), but never before had women been in charge of them. They faced mockery from those who thought it was improper for women to take on these positions of authority. Overcoming this ridicule became a crucial task for suffragists who understood the immense importance of voting rights. Such mockery was on display in the 1859 Harper’s Weekly cartoon below.

“Ye May session of ye woman’s rights convention—ye orator of ye day denouncing ye lords of creation,” Harper’s Weekly, June 11, 1859. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Male Allies

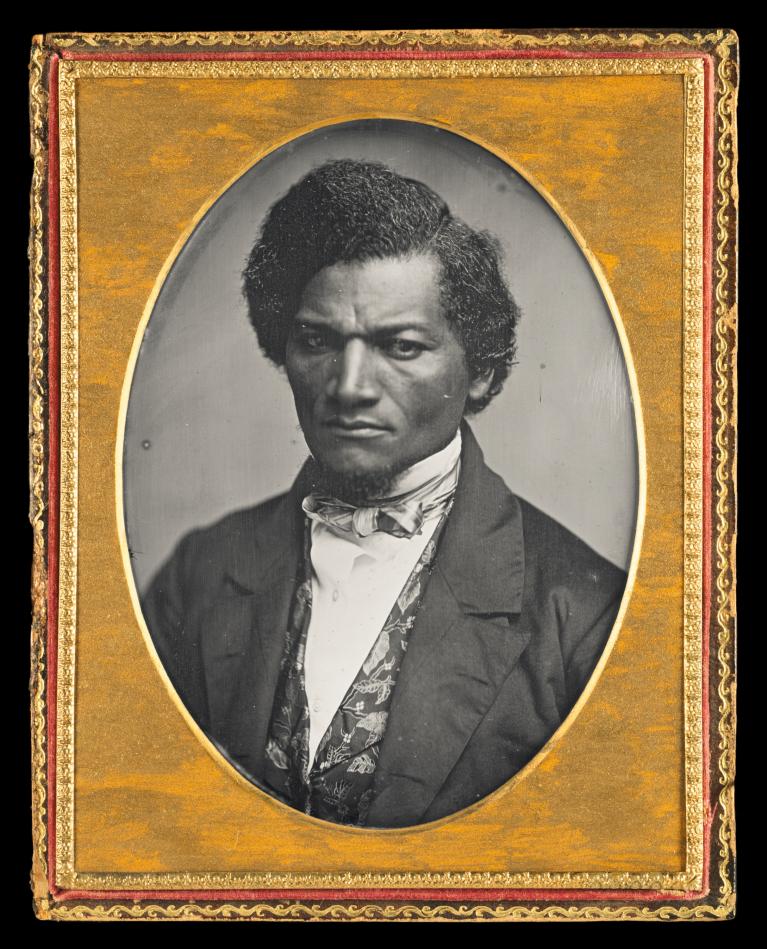

Women campaigning for suffrage also received support from some men, particularly those aligned with the abolition movement. Social reformer Henry Blackwell, Lucy Stone’s husband, often spoke out in favor of women’s suffrage. The famed abolitionist, orator, and civil rights advocate Frederick Douglass attended the 1848 Seneca Falls convention. There, his strong support for Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s controversial resolution seeking suffrage for women resulted in its narrow approval and inclusion in the Declaration of Sentiments. It was the only resolution passed without unanimous approval. Reflecting on his past at the Twentieth Annual Meeting of the New England Woman Suffrage Association in Boston, Douglass declared:

“I am a radical woman suffrage man. I was such a man nearly fifty years ago. I had hardly brushed the dust of slavery from my feet and stepped upon the free soil of Massachusetts, when I took the suffrage side of this question. Time, thought and experience have only increased the strength of my conviction. I believe equally in its justice, in its wisdom, and in its necessity.”

Douglass also highlighted the connection between the women’s suffrage movement and the abolition movement:

“In some respects this woman suffrage movement is but a continuance of the old anti-slavery movement. We have the same sources of opposition to contend with, and we must meet them with the same spirit and determination…”

Frederick Douglass

Utilizing Political Tools

Question: How could women express their political views when they did not have the right to vote?

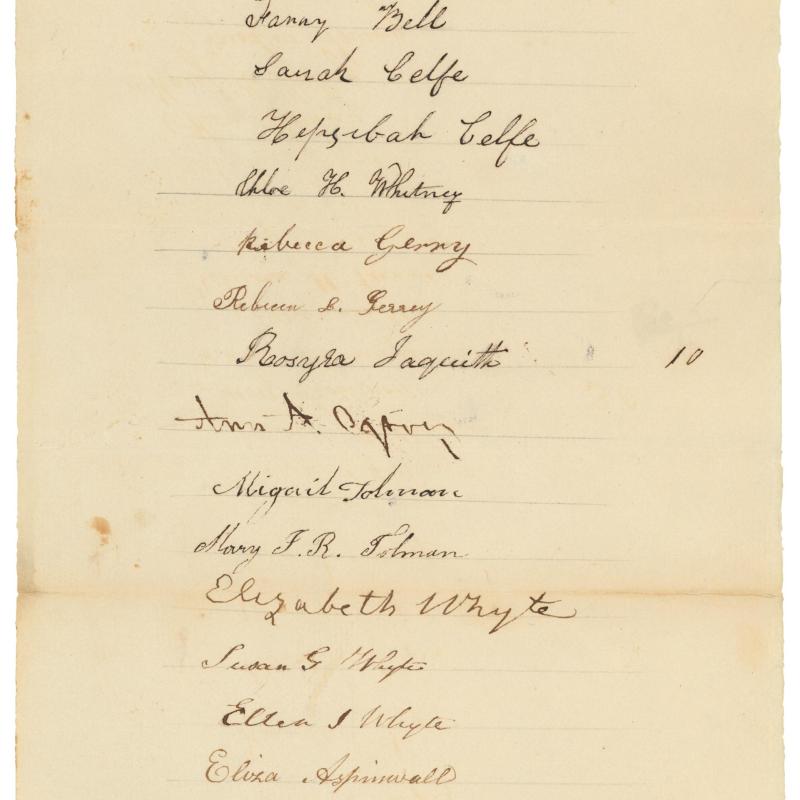

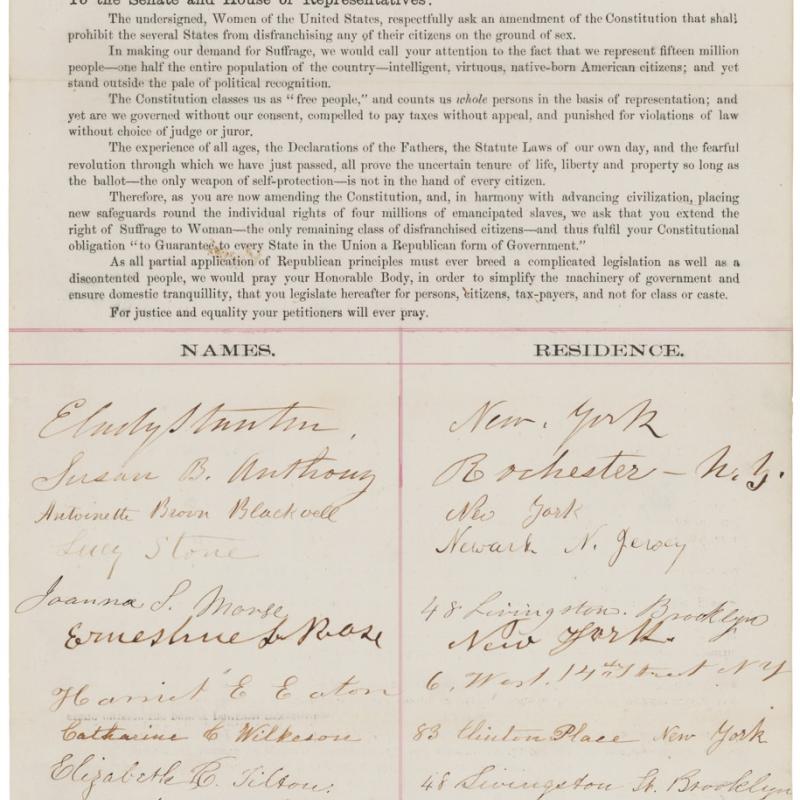

While forging new paths for women by speaking publicly and holding conventions, Massachusetts suffragists also took advantage of two other important political tools: petitions and hearings.

When Angelina Grimké testified before the Massachusetts State Legislature in 1838, it was her presentation of 20,000 signatures from her fellow women that enabled her to address a committee on antislavery petitions. Petitioning the legislature was the only way (other than writing individual letters) for women to express their political opinions at this time – it was the closest thing they had to a voice in the government.

As the suffrage movement grew, they submitted petitions to state legislatures and to Congress in order to demonstrate public support for their cause. For example, Abigail May Alcott (the mother of Little Women author Louisa May Alcott) petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for women’s suffrage in 1853. She wrote:

"We deem the extension to women of all civil rights, a measure of vital importance to the welfare and progress of the State. On every principle of natural justice, as well as by the nature of our institution, she is as fully entitled as man to vote, and to be eligible to office."

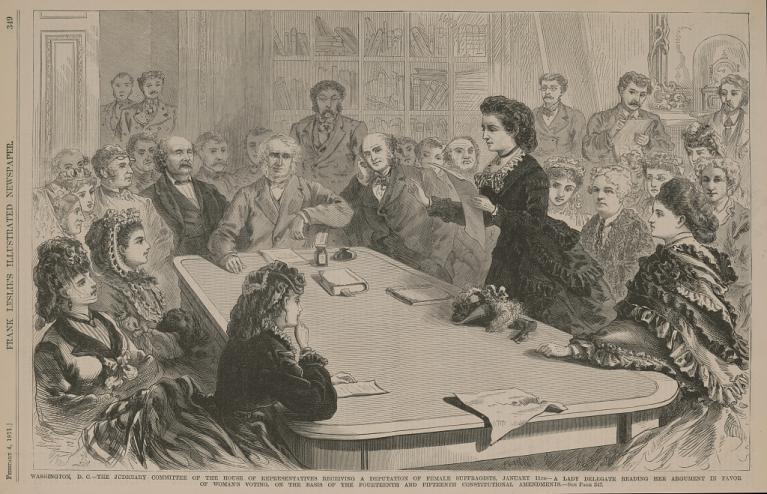

Today, the internet and social media networks provide additional methods that make it much easier to circulate petitions, but in the 19th century collecting signatures meant traveling by horse and buggy and going door-to-door or attending gatherings in search of signatures. When they had amassed enough signatures, suffragists presented their petitions to the government, just as the Grimké sisters had in 1838. In some cases, the legislature held hearings regarding the petitions. These hearings were some of the earliest examples of women testifying in State Houses and Congress, a historic step forward for women entering the public sphere of politics.

Bringing Suffrage to State Legislatures

The Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives receiving a deputation of female suffragists, January 11, 1871. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

In 1869, Lucy Stone testified before a joint committee on women’s suffrage at the Massachusetts State House. Two years earlier, when she was living in New Jersey, she had similarly appeared before the New Jersey state legislature and declared:

“It is no new claim that women are making. They only ask for the practical application of admitted, self-evident truths. If ‘all political power is inherent in the people,’ why have women, who are more than half the entire population of this State, no political existence? Is it because they are not people?”

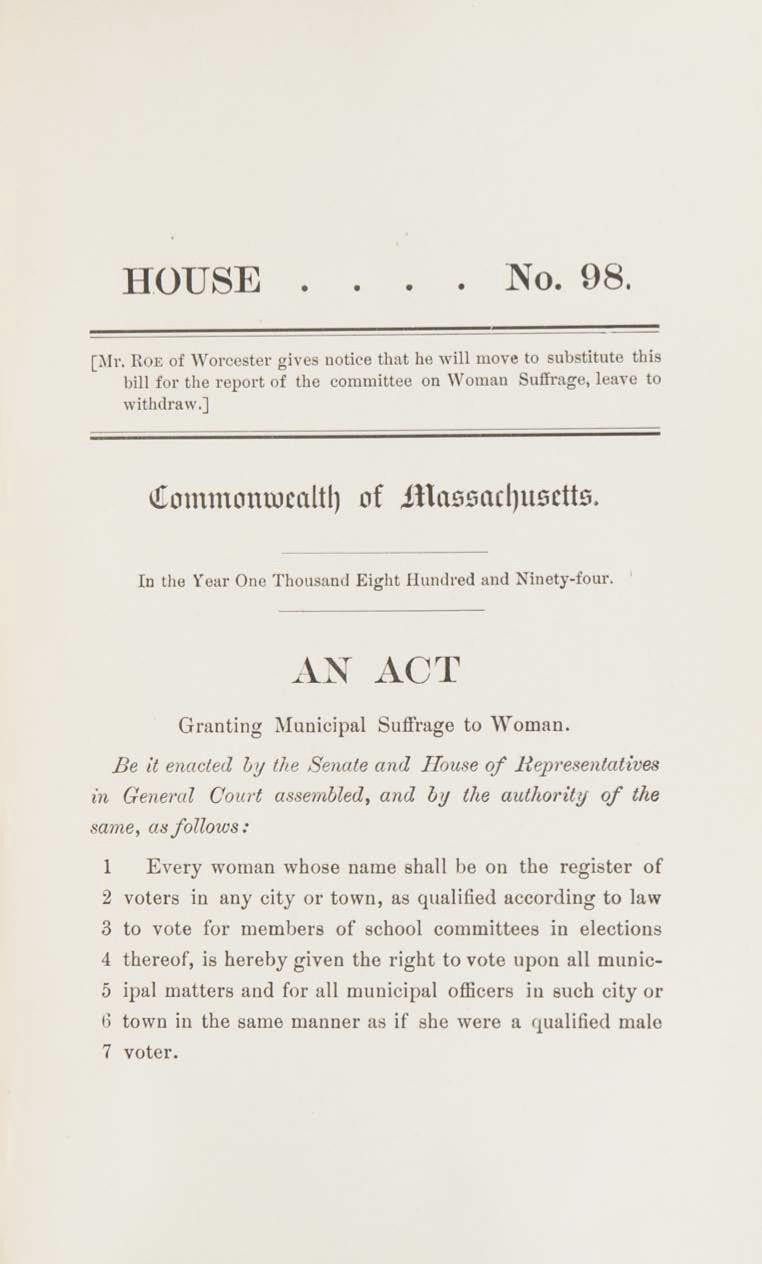

Legislative hearings about women’s suffrage continued throughout the movement’s history, including in Massachusetts. Hearings facilitated progress along the way, such as in 1879 when they led Massachusetts to enact partial suffrage rights for women by granting them the right to vote in local school board elections (viewed as an extension of their “home” sphere duties taking care of children). Most importantly, legislative hearings provided suffragists a forum to voice their arguments for women’s right to vote.

Stone’s 1867 testimony before the New Jersey state legislature demonstrated several of the varied strategies behind suffragists’ arguments:

“The essence of suffrage is rational choice. It follows, therefore, under our theory of government, that every individual capable of independent rational choice is rightfully entitled to vote.”

“They are counted in the census, and also in the ratio of representation of every State, to increase the political power of white men. Women are even held to be citizens without the full rights of citizenship, but to bear the burden of ‘taxation without representation,’ which is ‘tyranny.’”

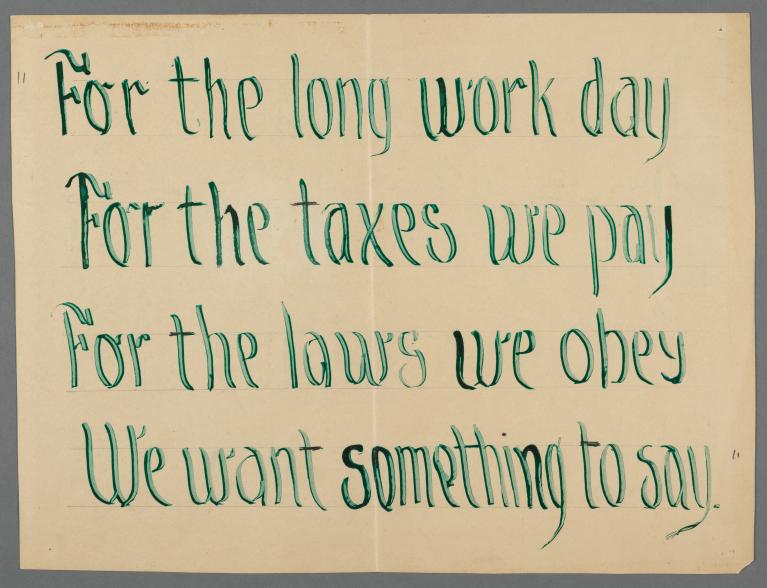

No Taxation Without Representation

One of the suffragists’ most compelling arguments highlighted the fact that women were required to pay taxes, yet had no voice in how their tax dollars were spent. They loudly declared that this was the exact same injustice that motivated the American Revolution: “No taxation without representation!”

Massachusetts suffragists came up with innovative tactics to draw attention to their strategy of “No taxation without representation.” Beginning in 1852, Boston physician Dr. Harriot Kezia Hunt, refused to pay her taxes on these very grounds. For more than 20 years, Hunt petitioned the City of Boston Tax Assessor’s office instead of submitting her payment. Her 1852 petition began:

“Harriot K. Hunt, physician, a native and permanent resident of the City of Boston, and for many years a tax payer therein, in making payment of her city taxes for the coming year, begs leave to protest against the injustice and inequality of levying taxes upon women, and at the same time refusing them any voice or vote in the imposition and expenditure of the same.”

While there is no record that the government responded to her petitions (or penalized her for not paying her taxes), Hunt’s petitions were published in newspapers across the Northeast and Midwest. Hunt had been one of the organizers of the 1850 National Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester, and she spoke at similar conventions throughout the country in the 1850s, amplifying the reach of her message about the injustice of taxing disenfranchised women.

Hunt was not alone in her protests. In 1863, Sarah E. Wall, an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate from Worcester, refused to pay her taxes on the same grounds of “no taxation without representation.” So too had Lucy Stone, while she was living in New Jersey in 1858. Unlike Hunt, both Wall and Stone faced penalties for their protests – each had their property seized by local officials and auctioned off in order to pay their tax debts. (In Stone’s case, her neighbors purchased her household belongings and returned them to her. In Wall’s, she was so steadfast in her refusal to pay year after year that the tax assessor eventually gave up trying to collect from her!)

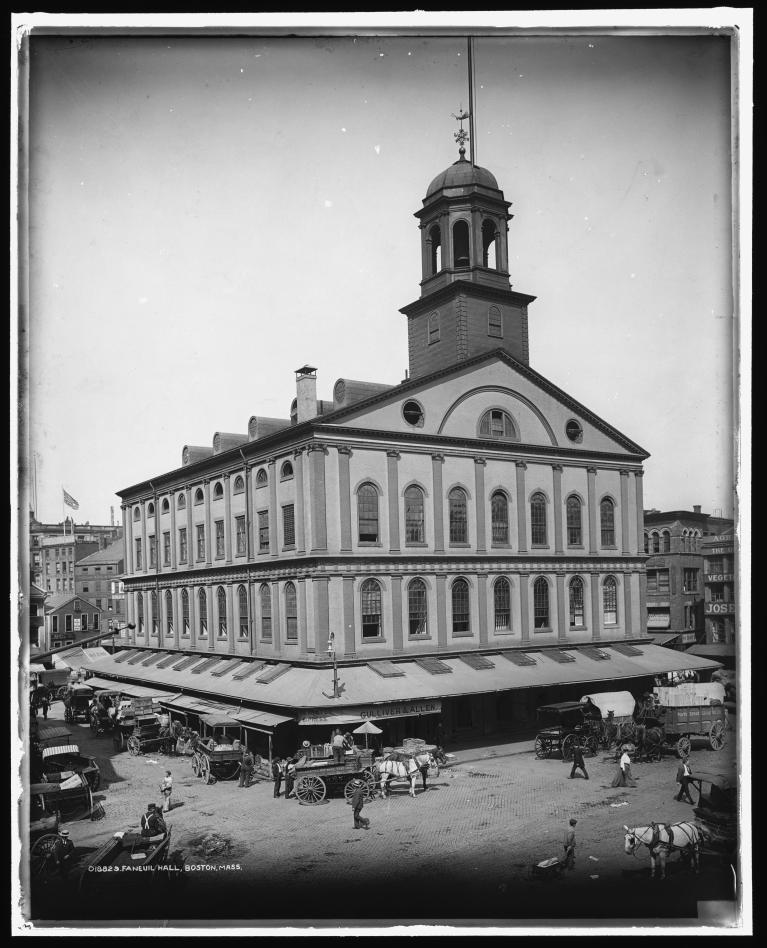

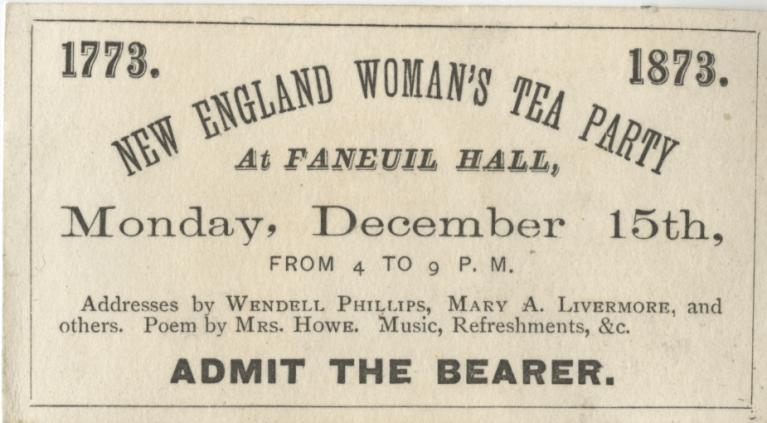

The Other Boston Tea Party

Eager to capitalize on this connection between the suffrage cause and the Revolutionary War, Bay State suffragists held a rally at Faneuil Hall on the 100th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party. “The New England Woman’s Tea Party,” featured speeches, music, and, of course, plenty of tea.

Question: How do you think the situations were the same or different for the colonists in 1773 and the suffragists a century later?

Three thousand people gathered in Faneuil Hall as the speakers strategically emphasized the similarity between women seeking the vote and American colonists who stood up to British tyranny. Like Thomas Jefferson when he listed Americans’ grievances in the Declaration of Independence, suffragists at the Tea Party detailed the numerous injustices that women faced as a result of their inability to vote: lower wages, limited property rights, no juries of their peers, and many others. Mary Livermore, an editor of The Woman’s Journal and a co-founder of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA), declared:

“The Woman Suffrage movement has been often spoken of as a new movement. It is, but it is based on old principles–the principles that were fought for and maintained on the field of battle nearly a hundred years ago. It is simply a carrying out of the principles further than our fathers carried them a hundred years ago.”

Kiley, M. J., printer. Collection of the Boston Athenæum.

Getting Out the Message and Controlling the Narrative

In order to gain broad public support, suffragists had to reach more people than they could with in-person speaking tours and legislative hearings. They had to make use of the number one mass communication tool of the day: newspapers.

Since before the American Revolution, newspapers have played an important role as a forum for civic debate and a way to persuade the public on political issues. Like nearly all civic institutions in the United States in the mid-19th century, the media was controlled and operated by white men. At first, the notion of women’s suffrage was so radical that most publications didn’t mention it at all. But as the movement grew, newspapers and magazines began to cover it, often with condescension, mockery, and even hostility.

Suffragists understood that they had to represent themselves in the media, rather than rely on depictions by men who scoffed at their ambitions. The surest way to avoid misrepresentation by the media was to publish their own newspapers, and Massachusetts suffragists led the charge.

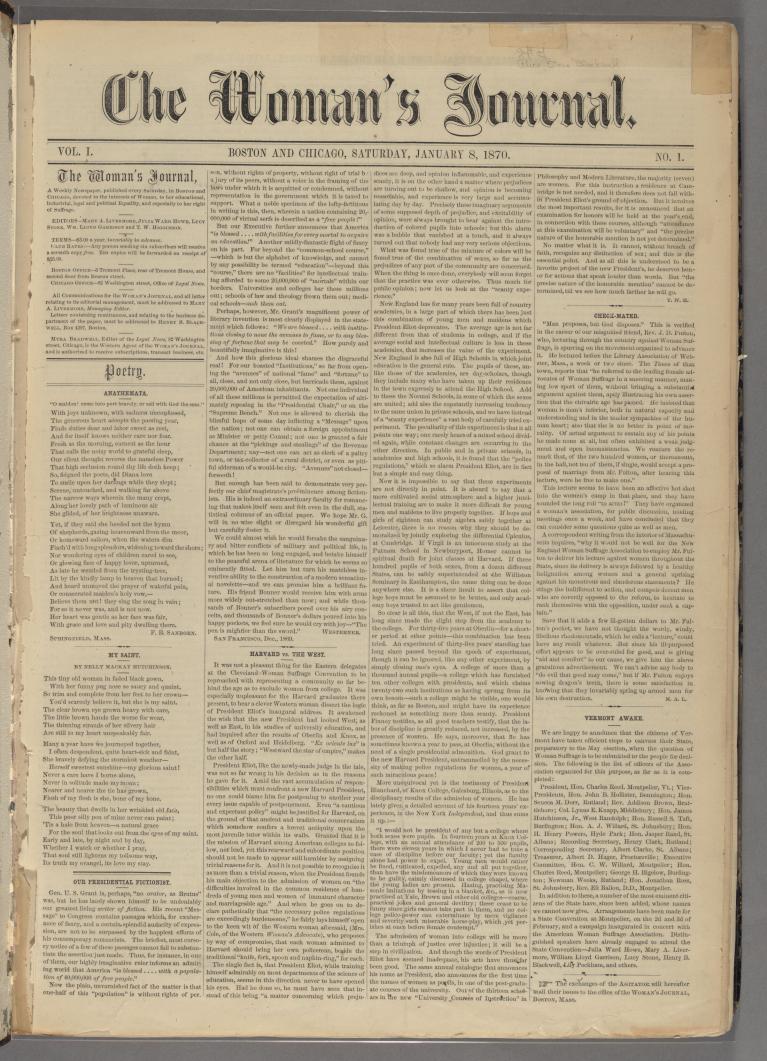

The Woman's Journal

In 1870, Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell founded a suffrage newspaper called The Woman’s Journal. Boston-native Mary Livermore, a teacher, journalist, and Civil War nurse, served as the newspaper’s first editor-in-chief. In the inaugural issue, Livermore laid out the publication’s mission:

“For the purpose of ‘pushing things’ the Woman’s Journal is established… Let us ‘push things’ with such unanimity of energies, such buoyant and uplifting faith in our sure ultimate victory, that not only Massachusetts, but every state in the Union shall speedily surrender to the advocates of woman’s equality and elevation.”

"The Suffrage Bible"

For the next 50 years, The Woman’s Journal functioned as the mouthpiece of the suffrage movement throughout the nation. It enabled suffragists to communicate the advantages of votes for women directly to the public. The regular movement updates provided by The Woman’s Journal also fostered a sense of community and solidarity among suffragists across the country that bolstered their connection to the cause. In addition to its paid subscribers, suffragists strategically distributed copies of “the suffrage bible,” as The Woman’s Journal was called, to legislatures, libraries, ministers, and teachers across the country in an effort to gain supporters.

“I read [The Woman’s Journal], lend it to my neighbors, and send it to hospitals, prisons, country libraries.”

Louisa May Alcott

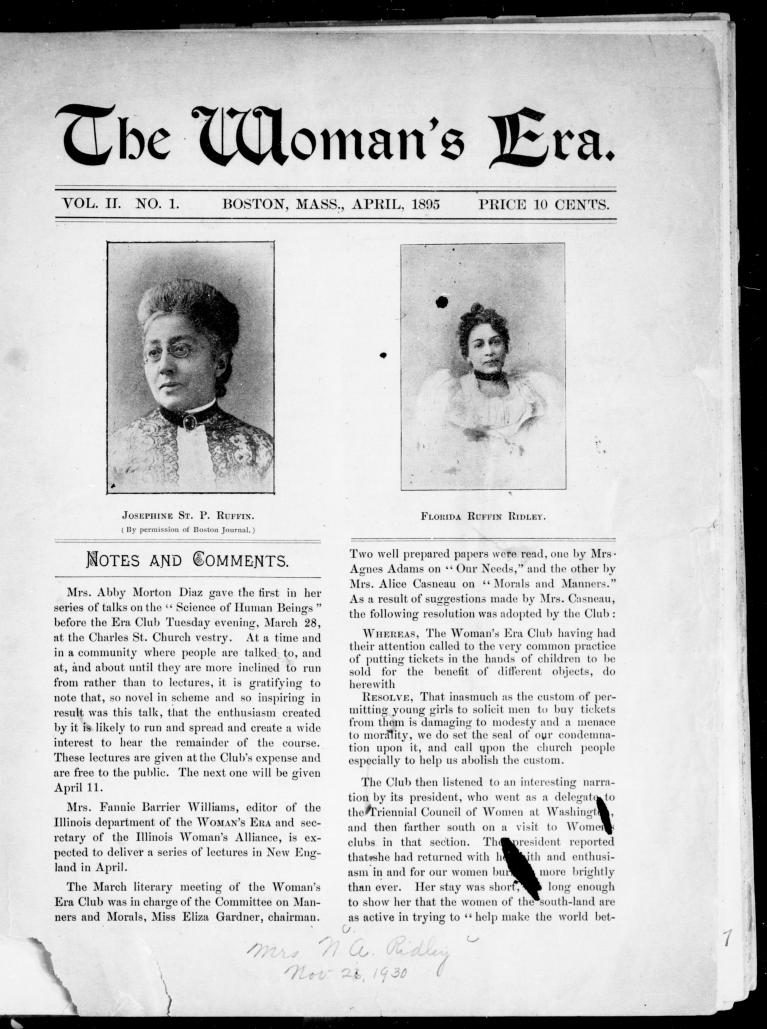

African American Suffragists Found The Woman's Era Journal

African Americans also established their own newspapers in order to ensure fair coverage, make their voices heard, and to foster a sense of group solidarity and pride. The Black press was a vital institution in the African American community during the Jim Crow Era.

The Woman's Journal was not the only important national newspaper advocating for suffrage that was born in Massachusetts. In Boston in 1894, African American suffragists and civil rights advocates Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Florida Ruffin Ridley (Josephine’s daughter), Maria Louise Baldwin, and Ida B. Wells founded The Woman’s Era, a journal connected with the club of the same name they had established a year earlier. It was the first national newspaper created by and for Black women.

Both the Woman’s Era Club and the newspaper dealt with a wide array of issues affecting African American women, such as education, employment, and discrimination – including drawing attention to the horrific lynchings of Black people – and their stance on the suffrage question was clear. Addressing their readership of Black women, The Woman’s Era’s editors declared: "This class [of women] has everything to gain and nothing to lose by endorsing the woman suffrage movement."

Other leading Black suffragists of Boston were active in the Women’s Era Club, including Arianna Sparrow. Sparrow and Ruffin worked with the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) in Boston’s Beacon Hill and West End neighborhoods, to encourage Black women to vote in school elections and Black men to support pro-suffrage candidates. In 1887, Sparrow helped found a primarily Black MWSA chapter, the West End Woman’s Suffrage League.

“We are justified in believing that the success of this movement for equality of the sexes means more progress toward equality of the races.”

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin

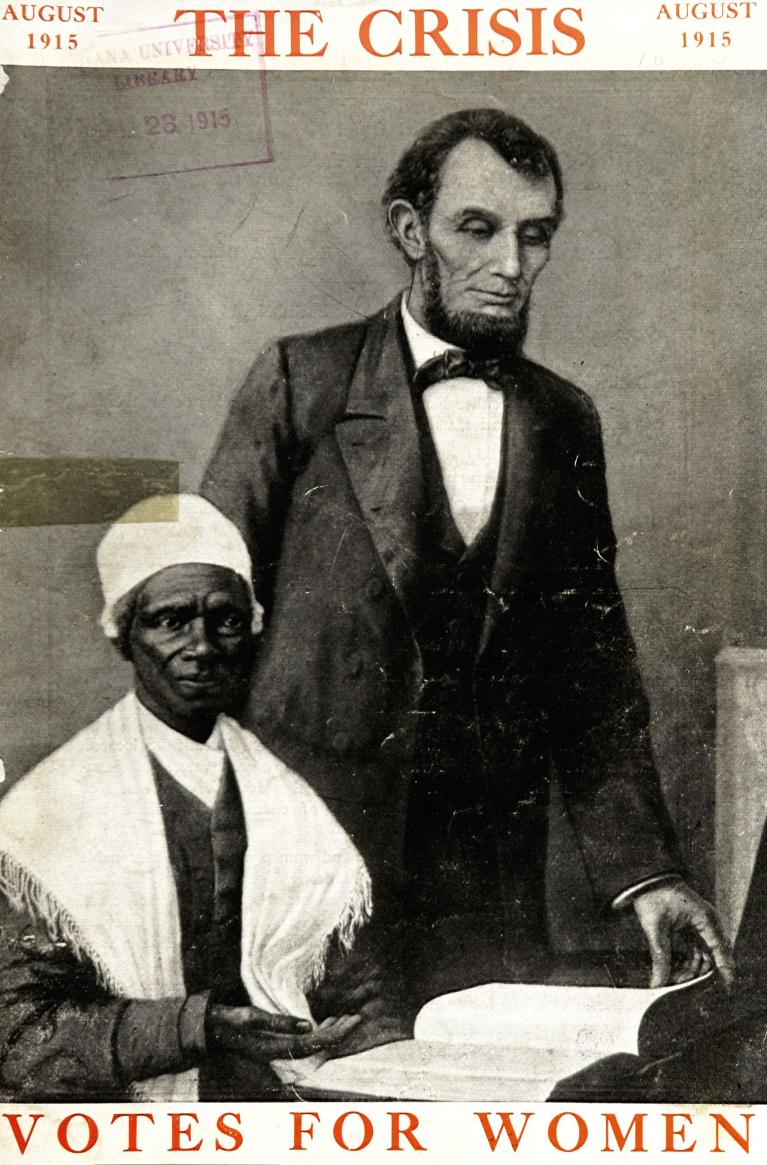

Working with The NAACP

The Woman’s Era ceased publication in 1897, but Ruffin, Baldwin, and other founders of the newspaper continued their efforts to expand rights for African Americans and women. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established in 1909 and Ruffin was one of the founding members of the Boston branch in 1910. That same year, it began publishing a magazine called The Crisis, which still exists today. The Crisis published a special issue in August 1915 titled, “Votes for Women.” It featured essays from a range of Black leaders arguing for the many benefits that would result from enfranchising women, especially for the African American community.

Massachusetts’ own Ruffin and Baldwin each contributed essays to the special issue. Baldwin, a prominent educator in Cambridge, authored, “Votes for Teachers.” Ruffin’s piece, “Trust the Women!” sought to address fears that enfranchising women would increase the number of white people who would vote against the interests of Black people. She described her positive experiences with white suffragists in her home state:

“I was welcomed into the Massachusetts Woman’s Suffrage Association by Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe, Ednah Cheney, Abby Morton Diaz and those other pioneer workers who were broad enough to include ‘no distinction because of race’ with ‘no distinctions because of sex.’”

Ruffin continued, connecting the battle for suffrage to the cause of racial equality: “We are justified in believing that the success of this movement for equality of the sexes means more progress toward equality of the races.”

Countering the Caricature

Question: Imagine a suffragist: What do they look like? How are they dressed? Where are they and what are they doing?

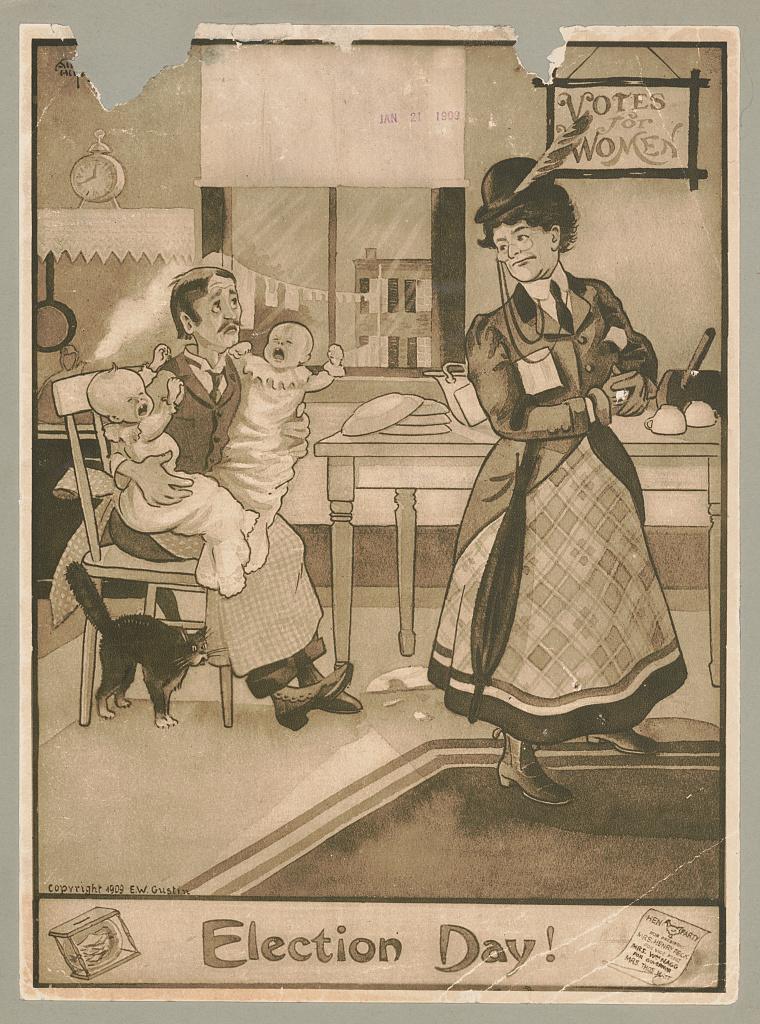

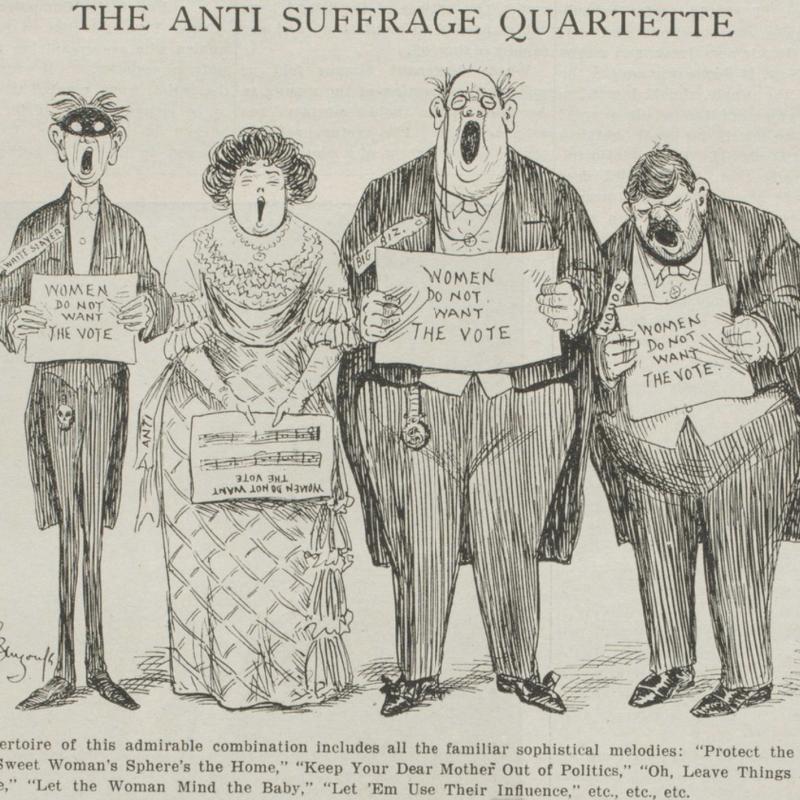

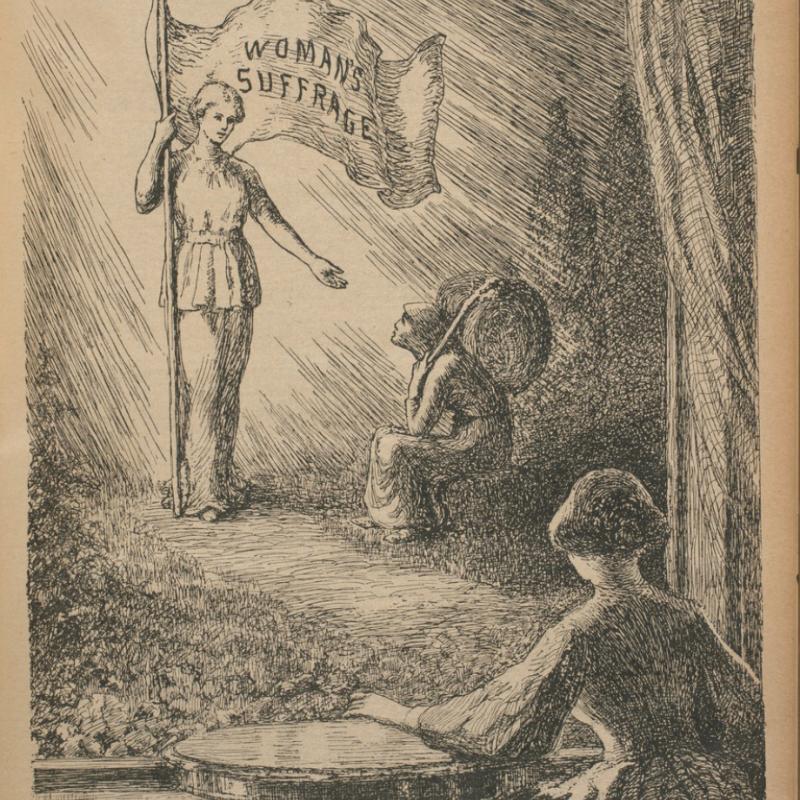

Suffragists understood that to build public support for their cause, they had to do more than set out their arguments in writing. They needed to counter the image of physically unattractive suffragists that appeared in most newspapers and magazines. Mainstream press outlets often featured demeaning caricatures of suffragists, depicting them as lonely spinsters or neglectful wives and mothers (such as the woman leaving her family to vote in the "Election Day!" cartoon). These caricatures portrayed women as unfit for the duties of citizenship.

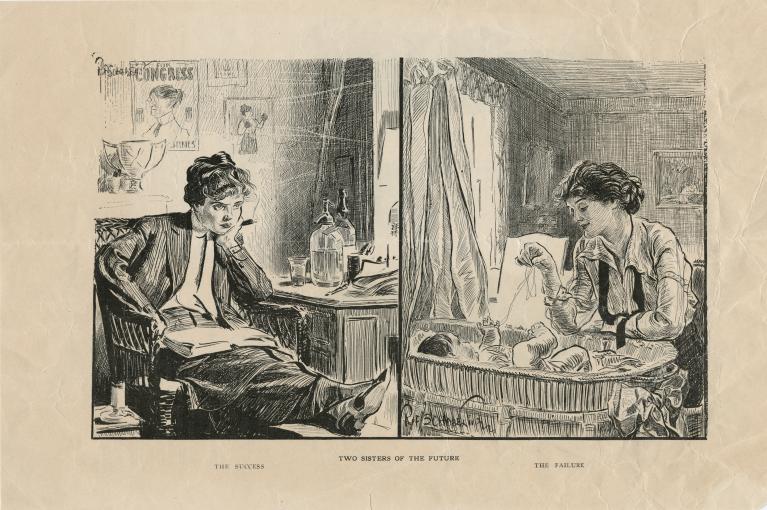

The anti-suffrage cartoon below illustrates the fears held by opponents of suffrage: the smoking, drinking career woman in her office is considered a success, while the doting mother who remains at home constitutes a failure.

Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Political Cartoons

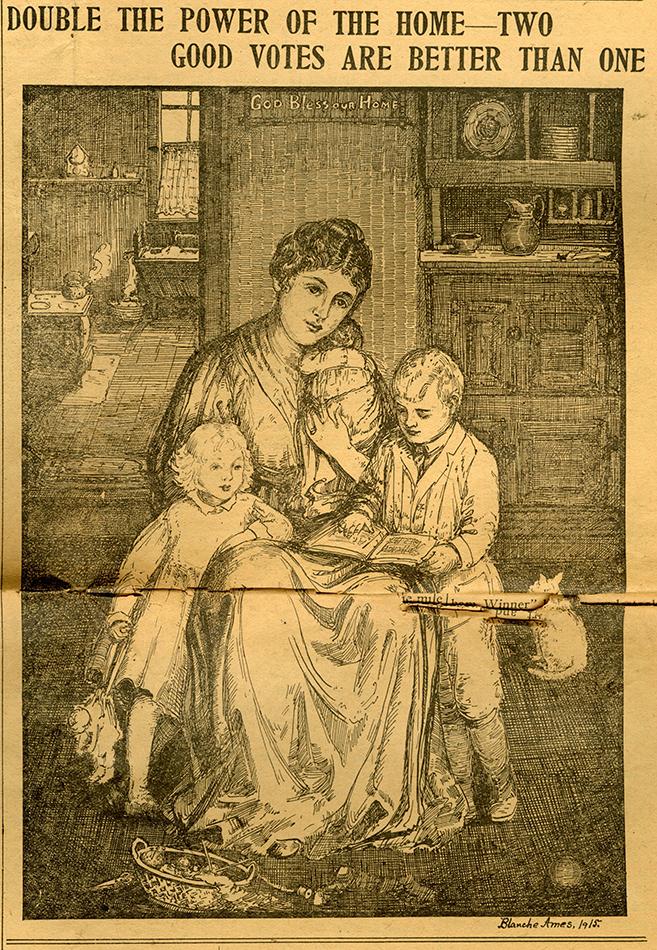

Blanche Ames Ames, a painter and illustrator from Easton, became one of the nation’s most prominent political cartoonists for women’s suffrage in the early 20th century. (She was also a writer, inventor, and reproductive rights advocate. Check out her MWHC biography to learn more!) By 1915, she was the art editor of The Woman’s Journal, which published many of her cartoons.

In her cartoons, Ames sought to depict suffragists as upright, responsible citizens as well as models of femininity. By combining these traits that opponents claimed were contradictory, Ames strategically countered the caricature of suffragists with images designed to appeal to the public.

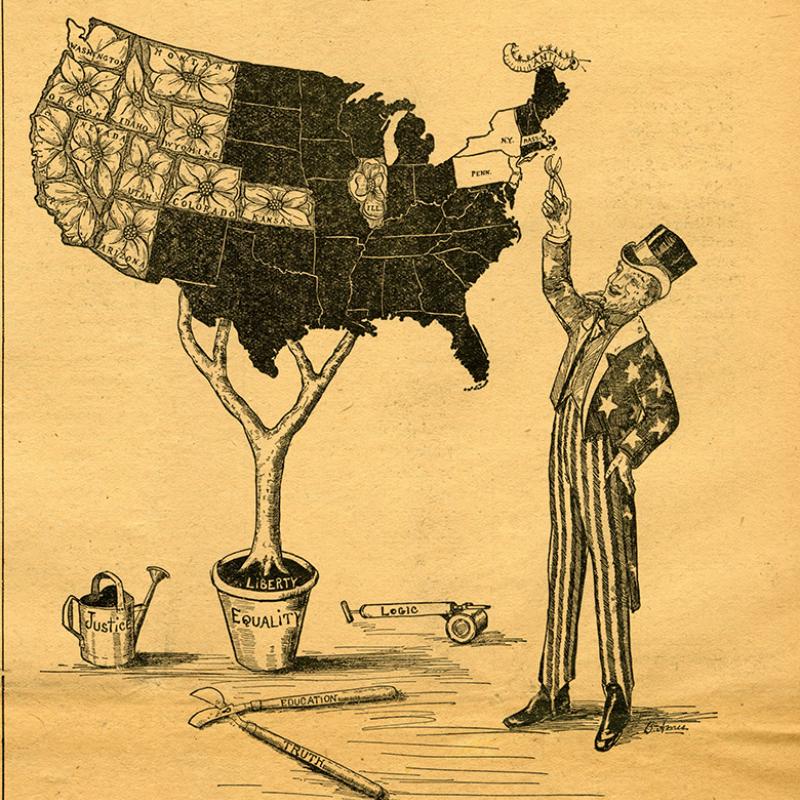

The general strategy with pro-suffrage cartoons was to depict the suffragist as feminine, maternal, logical, and above all, not radical. Suffrage cartoonists also aimed to turn the tables on anti-suffragists by portraying them as boorish, uncaring, illogical, and behind the times.

Dressing the Part

When gathering in public, suffragists wanted to inspire reverence and respect from their audiences. Often, suffragists wore all white to be identifiable, to set themselves apart (usually from darkly dressed men) and to signify the virtue of their cause. Some went further, dressing in pageant costumes to represent idealized images, such as “Columbia,” the goddess-like personification of the United States, or the “New Woman,” the term for young, independent women of the era.

German actress Hedwig Reicher wearing the costume of "Columbia" with other suffrage pageant participants in front of the Treasury Building, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

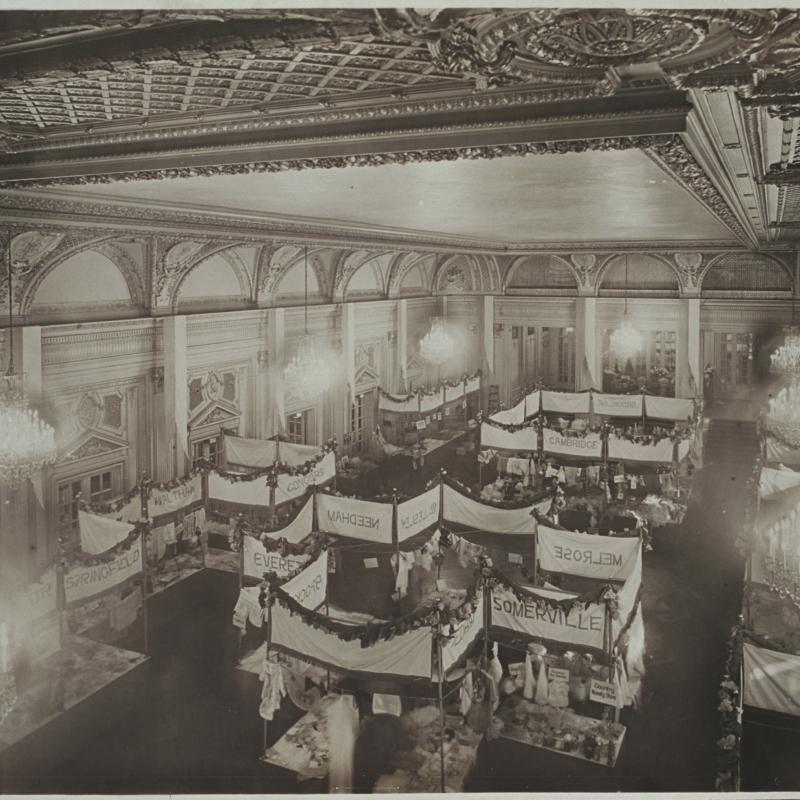

Funding the Movement

Just like campaigns today, the suffrage movement needed to raise lots of money to cover its costs, particularly as the movement expanded. Suffrage organizations had to pay for office space, supplies to publish their newspapers and fliers, lodging and meals for campaign workers out on the road, and many other expenses.

One way suffragists often raised funds was by hosting bazaars and rummage sales. In December 1871, for example, the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA) held a ten-day bazaar at the Boston Music Hall, where they sold apparel, decorative objects, books, and baked goods. Suffrage organizations from all around the Commonwealth participated and the event brought in between eight and nine thousand dollars for NEWSA. Julia Ward Howe, known for penning the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” was a leading Massachusetts suffragist. She coordinated the event in her role as president of the Woman Suffrage Bazaar Association, an organization dedicated to hosting bazaars to raise funds for the cause. A good friend of Lucy Stone’s, Howe also helped to establish The Woman’s Journal and co-founded multiple suffrage organizations in the Bay State.

Donations Keep the Movement Running

Suffragists also sought donations to fund the movement. Mary Hutcheson Page was a resident of Brookline, Massachusetts (and one of the first female students at MIT) who led multiple suffrage organizations in the Commonwealth. She specialized in fundraising by drawing new women to the movement and persuading them to make donations.

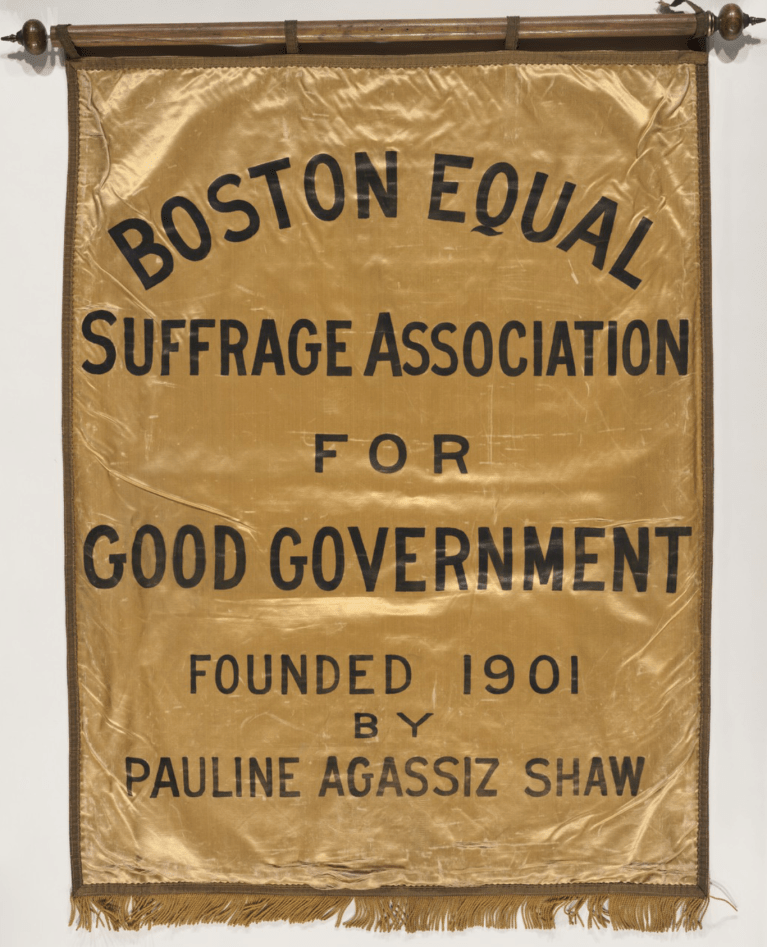

Pauline Agassiz Shaw, a prominent educator and social reformer in Boston, reportedly donated $30,000 (worth approximately $930,000 in 2023) to the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1913. It covered the salaries of NAWSA organizers in Massachusetts as well as their travel to nearly a dozen other states.

Partial Victories Lead to Big Opposition

Massachusetts women achieved a milestone on the path to full suffrage in 1879: the right to vote in school committee elections. In a few towns, women were allowed to vote in school committee elections as early as 1868, and Boston allowed the practice in 1874. Five years later, facing intense pressure from suffragists, the state legislature approved this limited voting right for women throughout the Commonwealth.

While this victory fell far short of suffragists’ goal of equal voting rights for men and women, the opportunity to vote in local school elections gave them a foot in the door and helped to normalize the idea of women going to the polls in the Commonwealth.

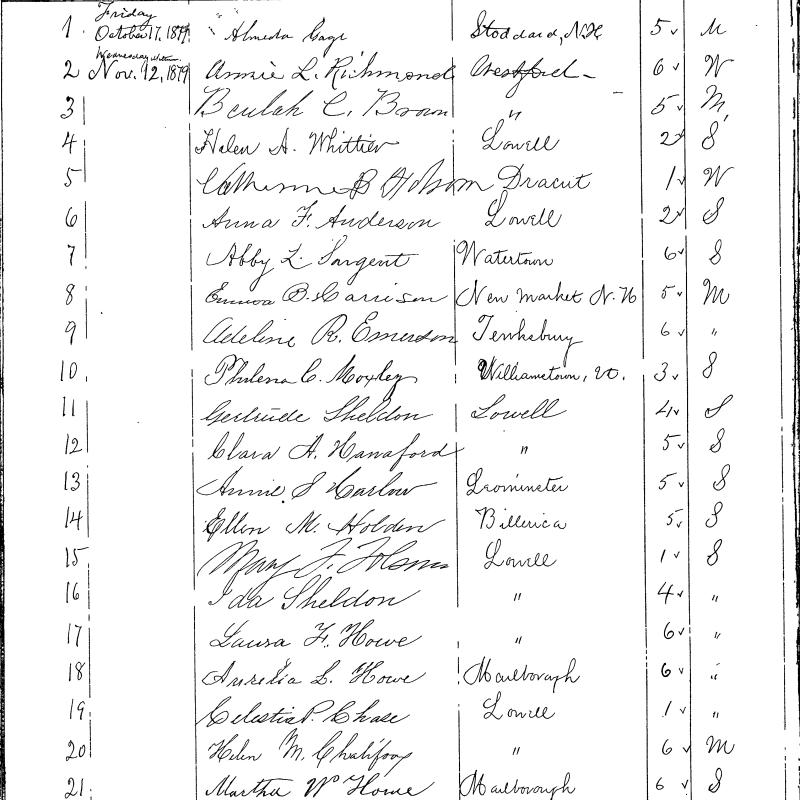

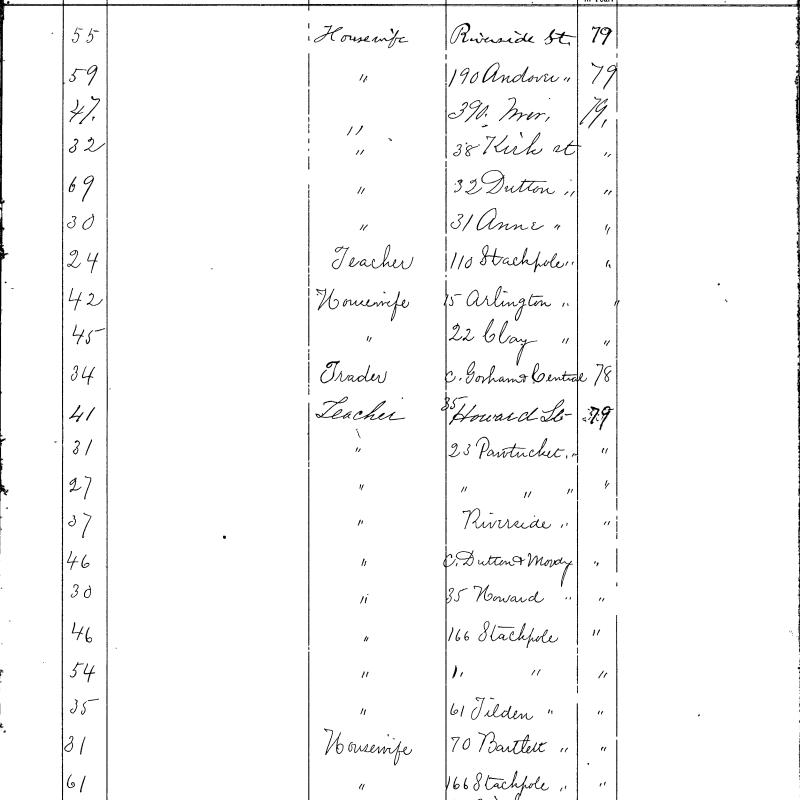

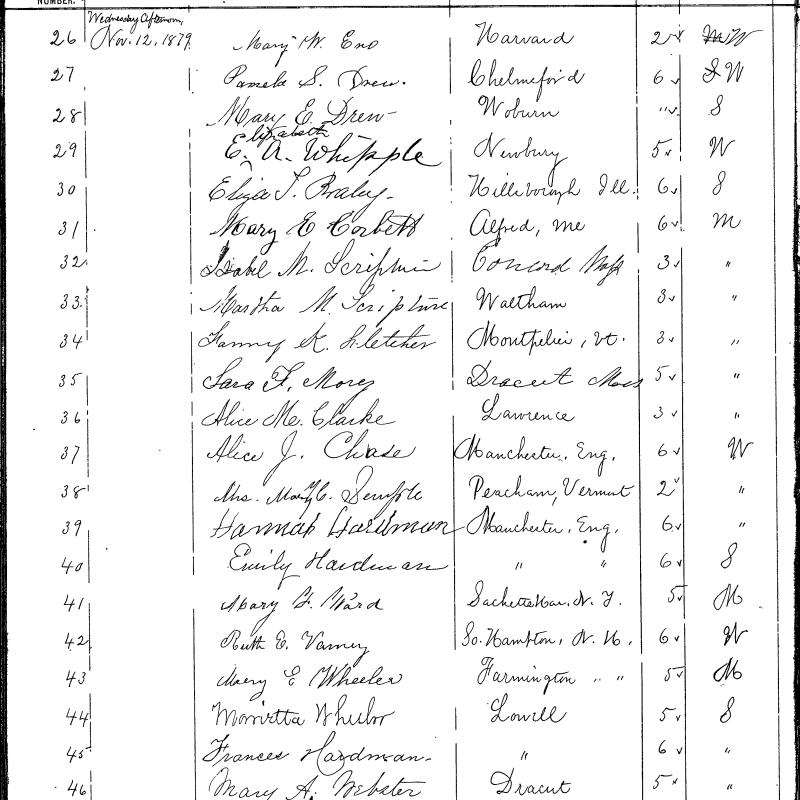

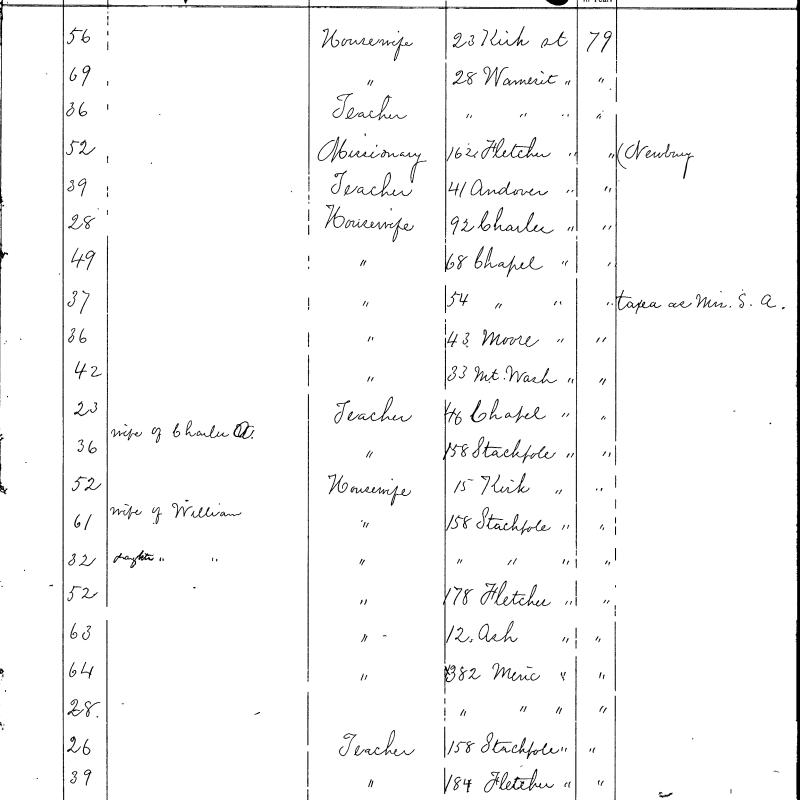

Lowell Women in the Voting Ledger, 1879

Below are excerpts from an 1879 ledger listing the Lowell women who registered to vote in school committee elections, the very first elections for which Massachusetts allowed women voters! The full ledger contains entries for 152 women, including their names, birthplaces, marital status, occupations, addresses, and taxes paid in the previous year.

Concord's Women Cast Their Votes

Question: How do you think it felt for a woman to vote in that very first school committee election?

In 1879, after women achieved the right to vote in school committee elections, author Louisa May Alcott was the first woman to register to vote in Concord. In the lead up to the town meeting on March 29th, she went door-to-door encouraging her fellow women of Concord to vote and held meetings at her home. Twenty women of Concord walked to the front of the hall together when the school committee election was called. Some of the men scoffed at the women who dared to vote, but Alcott described the moment with pride and nonchalance:

“No bolt fell on our audacious heads, no earthquake shook the town, but a pleasing surprise created a general outbreak of laughter and applause.”

Participating in school committee elections was seen by many at the time as a sensible extension of women’s natural roles as mothers and caretakers, particularly as they were understood to be in charge of the education of their young children. Voting on school matters seemed more acceptable to suffrage opponents than fully enfranchising women, though some opponents thought that even these partial suffrage rights went too far.

Voting in Local Elections

Massachusetts suffragists strategized to use the 1879 victory as a basis to fight for broader voting rights, like municipal suffrage (i.e. all local elections, not just school committees). They argued that women’s supposed domestic talents qualified them to take care of their local communities as well. By voting in municipal elections, they claimed, they could ensure clean streets, safe food, and adequate medical care for the community, just as they did at home for their own families. Here, Massachusetts suffragists strategically cloaked their argument for further suffrage in the traditional duties of marriage and motherhood, part of their effort to counter the claim that voting rights for women would constitute a radical change for society.

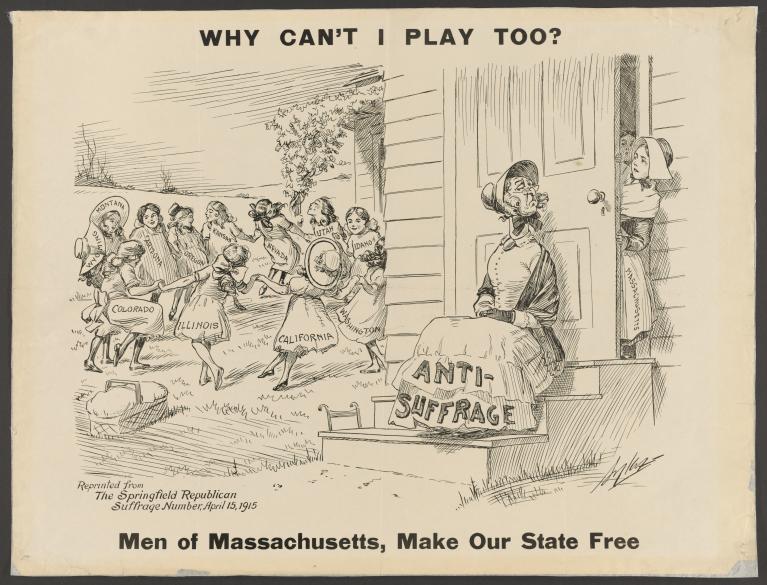

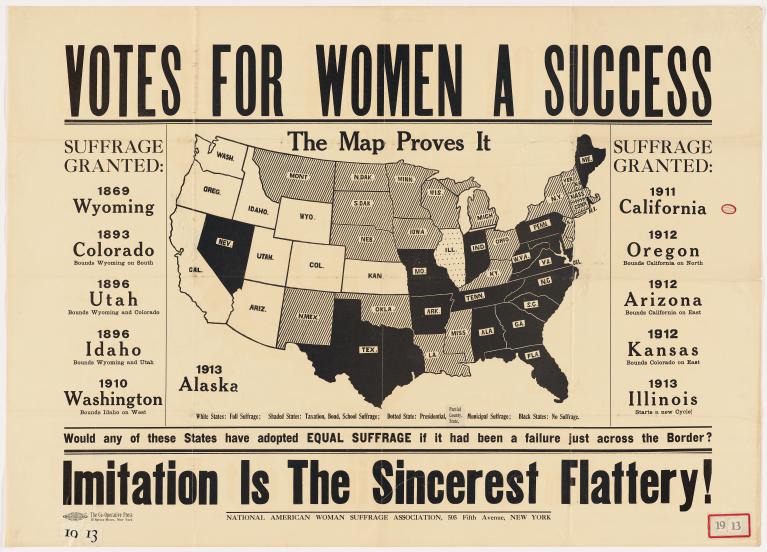

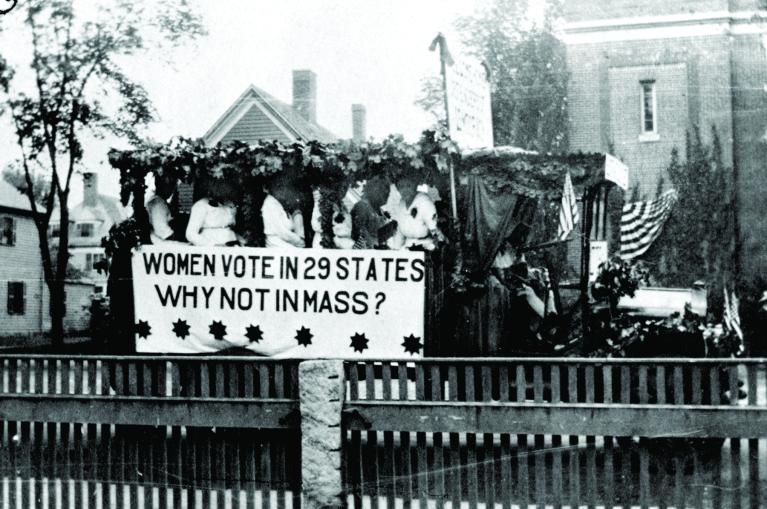

Bay State Suffragists Look to the West

Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Across the nation, Western states generally granted suffrage to women much earlier than Eastern states. Wyoming became the first state where women possessed full voting rights, even before Wyoming became a state! Wyoming’s territorial legislature granted suffrage to women back in 1869, and it became the first state where women could vote in 1890, when it was admitted to the Union. Several factors contributed to this trend, such as the West’s desire to attract female residents in order to balance out the predominantly male population. The separation of male and female spheres was also less prominent in the west, where men and women often worked side-by-side on their farms. Further, the older states in the East had more entrenched political traditions, so instituting a reform like suffrage was more challenging than in the Western states where those traditions had not yet been established.

Suffragists in Massachusetts pointed to the women in Western states as successful examples of female voters. They argued that within the Bay State, women had demonstrated their fitness to vote through school committee elections, and that out West, full voting rights for women led to greater civic participation and pride rather than the ruinous outcomes that suffrage opponents had feared.

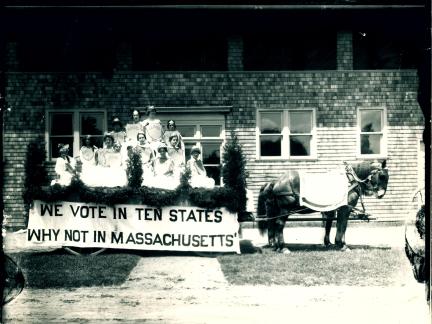

In Massachusetts, like much of the Eastern half of the United States, suffragists compared their home state unfavorably to the suffrage states of the West.

Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Main Street, Waltham, Mass. June 17, 1919. Waltham Historical Society.

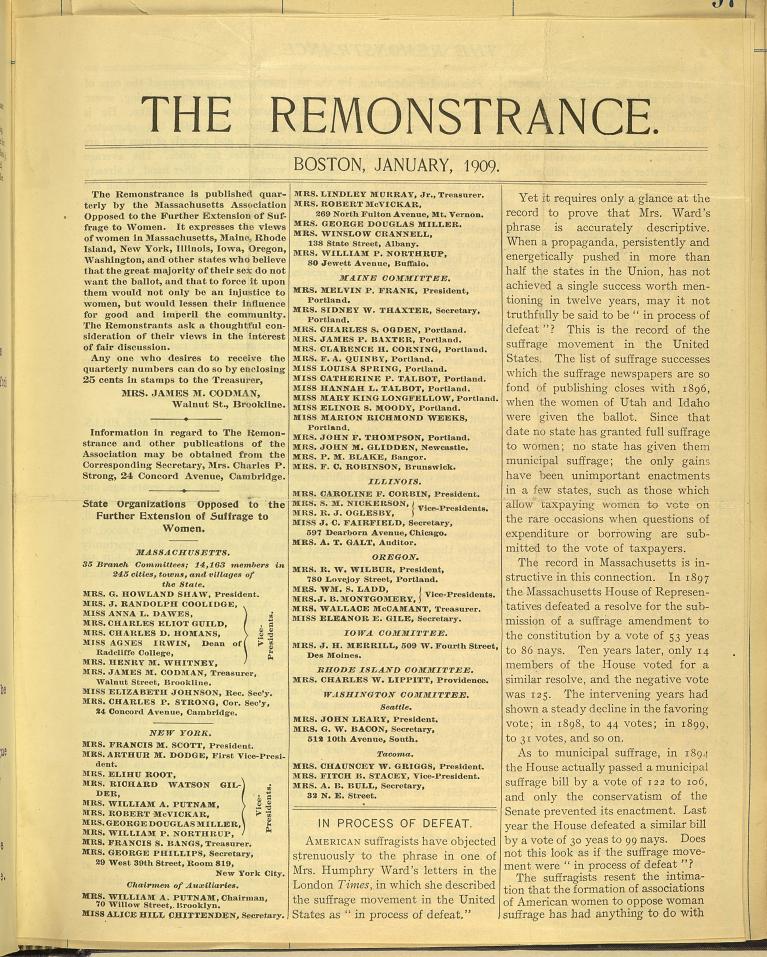

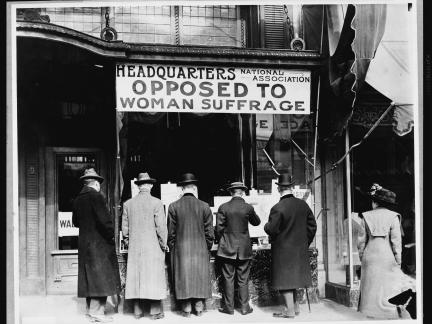

The Rise of Anti-Suffrage

In 1883, after Massachusetts women obtained the right to vote in school committee elections and suffragists had begun pushing for municipal voting rights, women from Boston’s elite circles who opposed suffrage started an informal organization called the Committee of Remonstrants. (Remonstrate means to oppose vigorously.) For over ten years, they met in each other’s homes and developed anti-suffrage literature that they distributed across the country with the help of their influential male relatives. In 1890, they began publishing The Remonstrance, a newsletter that represented the anti-suffrage movement just as The Woman’s Journal represented the suffrage movement.

In 1895, the Massachusetts legislature announced a nonbinding referendum on the question of municipal suffrage for women. Women who were registered to vote for school boards could take part in this election. In light of the referendum, the Committee of Remonstrants reorganized to form the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW).

The creation of MAOFESW marked a turning point in the suffrage battle, both in Massachusetts and nationwide. Previously, those opposed to voting rights for women had not formally organized like the suffragists, but now they acknowledged they were part of their own movement that sought to stop suffrage in its tracks. Still, MAOFESW members felt that politics was not an appropriate arena for women, so they acted behind the scenes and relied on their male relatives to speak for them in public settings.

The Opposition Grows

Anti-suffragists, also known as antis, won the 1895 referendum by a significant margin. The men who voted chose to deny municipal suffrage to women at a rate of two to one. The women who did cast their ballots strongly supported expanding women’s suffrage rights, but few who were eligible actually voted.

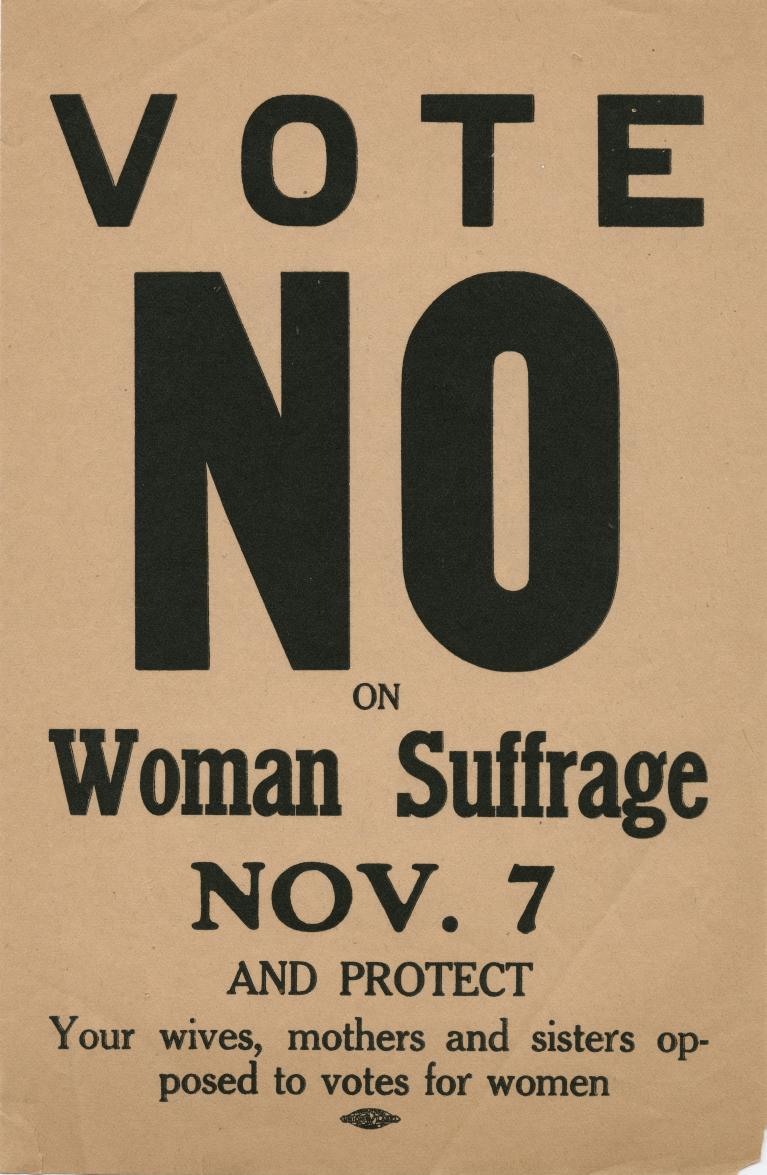

Victory in the referendum turned the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW) into one of the leading anti-suffrage entities in the country and, consequently, Massachusetts became known as a central hub of anti-suffrage organizing. The anti-suffrage arguments MAOFESW put forward spread across the United States. They claimed that few women wanted to vote, that women were already succeeding without the vote, and that suffrage would upend the entire social structure by pitting women against men. Excerpts from their fliers include:

“Some Reasons Why Women Oppose Votes for Women”

BECAUSE the demand for the ballot is made by only a small minority of women and the majority of women do not want it.

BECAUSE the great advance of women in the last century–moral, intellectual, and economic–has been made without the ballot, which goes to prove that the ballot is not needed for their further advancement along the same lines.

BECAUSE women, standing outside of politics, and therefore free to appeal to any party, are able to achieve reforms of greater benefit to the state than they could possibly achieve by working along partisan political lines.

“To the Working Man”

Working Men with families cannot compete with women who have only themselves to support.

Woman Suffrage is the opening wedge to feminism.

Feminism means competition of women with men in all fields of labor — in every trade and occupation.

The Antis Win Again

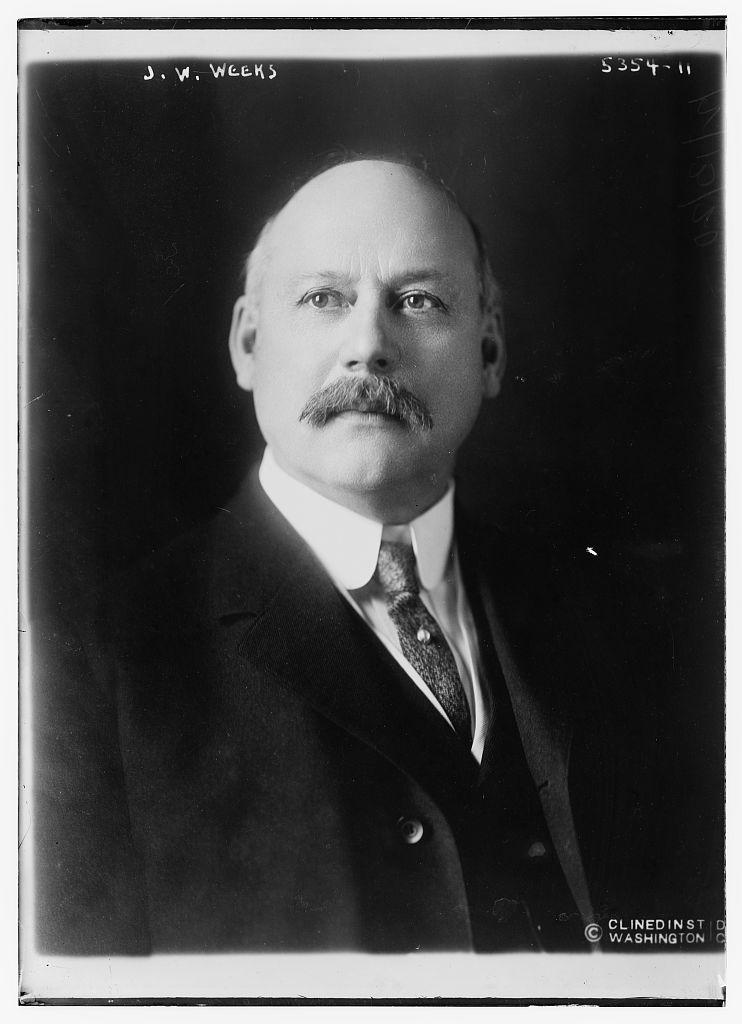

It was not just the work of MAOFESW that strengthened the anti-suffrage faction in Massachusetts. In the early 20th century, Massachusetts U.S. Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and John W. Weeks were two of the leading anti-suffrage members of Congress.

The anti-suffrage movement continued to grow in Massachusetts, reaching its peak in 1915, during the state’s second referendum on women’s suffrage. This time, it was not just municipal suffrage in question, but the right of women to vote in statewide elections. Crucially, the referendum was limited to male voters (meaning the Massachusetts women who voted in school board elections could not vote on this question). Again, male voters opposed women’s suffrage by a two-to-one margin. The strength of the anti-suffrage movement in Massachusetts made it more necessary than ever for suffragists to come up with original strategies and clever tactics in order to win the battle.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

New Allies Bring New Tactics

At the turn of the 20th century, in the wake of the 1895 defeat of municipal voting rights for women of Massachusetts the suffrage movement in the Commonwealth suffered a lack of energy and enthusiasm. They had been fighting for the ballot for half a century and had little to show for it in the Commonwealth besides the right to vote in local school elections. Lucy Stone, the mother of the movement in Massachusetts, had passed away in 1893. Her compatriots had reached old age. The movement needed new blood, and new blood is exactly what they got.

Question: What suggestions would you give to suffragists looking to breathe new life into their movement?

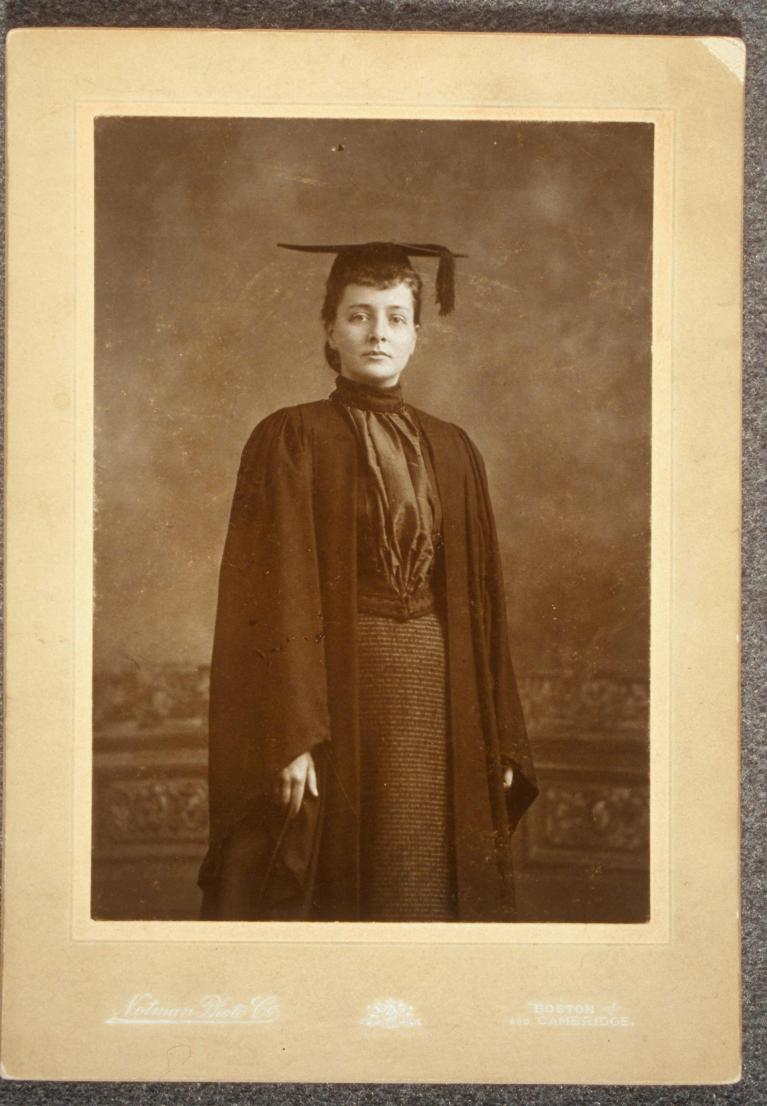

College Women Join the Fight

Maud Wood Park was a student at Radcliffe College when her English professor assigned an essay on women’s suffrage. Of the 70 students who completed the assignment, Park was one of only two who wrote in support of suffrage. She asserted:

“I see no more reason for the men of my family to decide my political opinions and express them for me at the polls than to choose my hats and wear them, or my religious faith and occupy my seat in church.”

Radcliffe graduate Maud Wood Park, 1898. Notman Photographic Co., Boston. Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

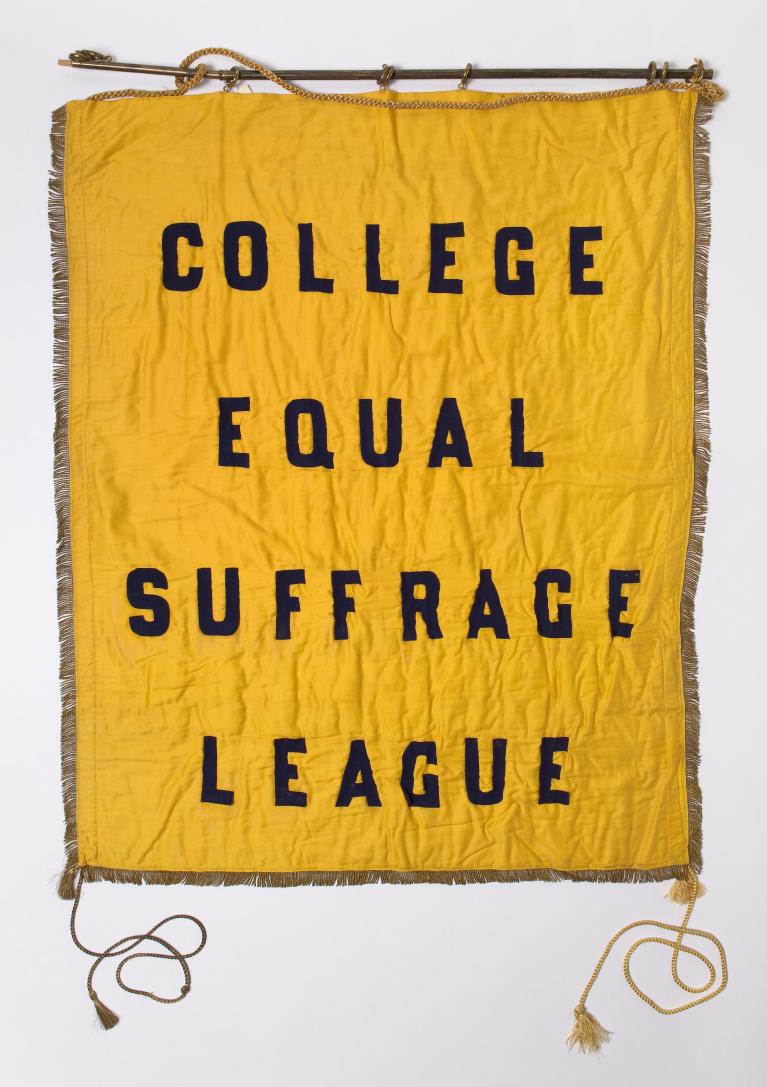

The College Equal Suffrage League

When Park learned that MAOFESW was hosting an anti-suffrage speaker at Radcliffe, she and her classmate Inez Haynes invited Alice Stone Blackwell (the daughter of Lucy Stone) to campus. Stone Blackwell and her fellow suffragists quickly recognized Park’s potential for leadership and sent her to the national suffrage convention in Washington, D.C. in 1900.

While there, Park was upset to find that nearly all the attendees were middle-aged or elderly. She felt indebted to the work older suffragists had done, but knew the movement needed new energy and new strategies. Together with Haynes, Park co-founded the College Equal Suffrage League in order to bring her fellow college-educated young women to the cause.

The College Equal Suffrage League’s (CESL) mission was to promote suffrage among alumnae and current students. The CESL quickly became active on New England campuses, sponsoring debates and essay contests, hosting lectures, and circulating pro-suffrage literature. By 1906, it claimed more than 250 members, by 1908 there were branches in 15 states, and by 1913, the Massachusetts branch alone included more than 450 young women.

The strategy of investing in a new generation of advocates would pay dividends in Massachusetts and nationwide as these young women renewed the spirit of the movement and brought fresh ideas to the table.

Forging Bonds Abroad and at Home

Another source of new ideas for Bay State suffragists was their sisters-in-arms across the Atlantic, English suffragettes. (The British press referred to militant suffragists as suffragettes in an effort to belittle them.) English suffragettes employed aggressive tactics such as publicly confronting members of Parliament, smashing shop windows, vandalizing postal boxes, and even setting fire to unoccupied government buildings and planting bombs in Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s Cathedral. They claimed that their violence was justified because they had exhausted all other means of protest but had not yet secured their right to vote.

Prominent American suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns went to England to further their education in the early 20th century. There, they each became involved in the English suffrage movement and actually met for the first time in jail after they were both arrested for marching on Parliament’s House of Commons in 1909. Both Paul and Burns endured brutal treatment while imprisoned in England, including hunger strikes and forced feedings. They returned to the U.S. in 1910, committed to nonviolence but also determined to be more forceful in their tactics.

Margaret Foley and Florence Luscomb, both of Massachusetts, each visited England as well, returning with new tactics, such as heckling politicians. English strategies were also brought to the U.S. by visiting suffragettes, including leader Emeline Pankhurst, who rallied support for suffrage in Boston in 1909. Pankhurst’s speech at Tremont Temple and reception at the Vendome Hotel raised funds for the British suffrage effort and provided Boston suffragists with ideas for new campaign tactics.

In addition to fostering bonds with college women and English suffragettes, Massachusetts suffragists also stepped up their outreach efforts with another important constituency of the era: labor union women.

The labor movement was growing in prominence at the end of the 19th century and women increasingly made up a significant portion of the laborers agitating for better working conditions. In 1903, Boston-native Mary Morton Kimball Kehew co-founded the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was the first national organization dedicated to organizing female laborers and improving their working conditions. It served as an umbrella organization for numerous women’s trade unions.

A number of suffrage leaders, many of whom were well-off financially, recognized that working-class women stood to benefit greatly from voting and that they had previously not done enough to form alliances with union women.

So the suffrage leaders corrected course, forming partnerships at the national level between NAWSA and the WTUL. By 1908, the WTUL had established its own suffrage department as well as wage-earners’ suffrage leagues for women who didn't feel at home in existing suffrage organizations. These partnerships also helped persuade union men that women’s suffrage would not hurt their livelihoods (as anti-suffragists claimed). Rather, the ballot would allow women to demand higher wages, which would raise wages for men as well. Soon, Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor, told suffragists that his organization was dedicated to “equal suffrage, equal rights, and equal pay.” By 1909, 235 unions in Massachusetts declared their support for women’s suffrage.

By recruiting new members and allies at the turn of the century, Massachusetts suffragists revived their movement and set the stage for a new tactical phase of the campaign: hitting the road and doing it in style.

Campaigning on the Street and in the Sky

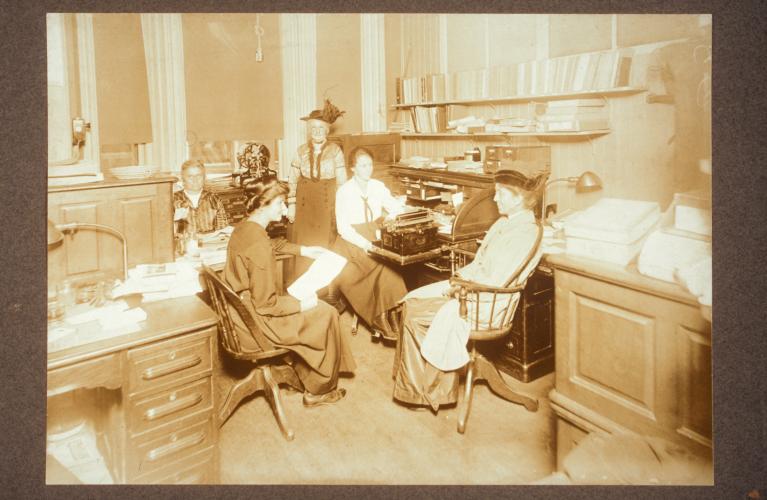

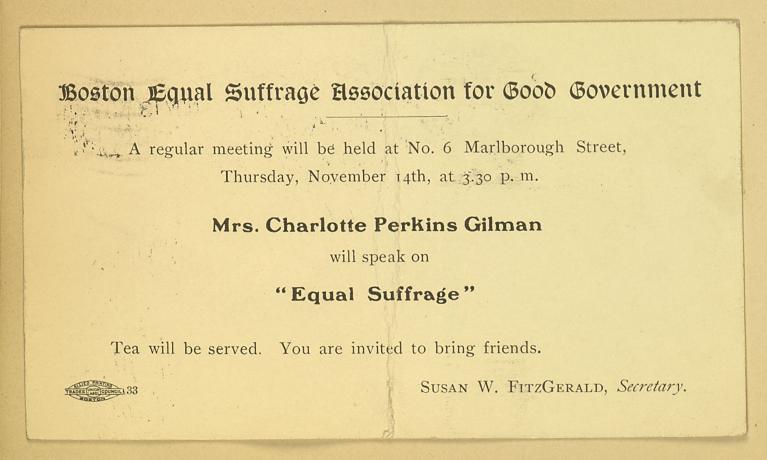

In 1901, Maud Wood Park, Mary Hutcheson Page, and Pauline Agassiz Shaw co-founded another important suffrage organization in Massachusetts: the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government (BESAGG). BESAGG began experimenting with innovative suffrage tactics, ushering in a new era for the movement, more than half a century after it began.

BESAGG office, 1917. Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Drawing a Crowd

In September 1908, four suffragists arrived in Lynn by automobile (still a novelty in 1908) with musicians in tow, and gathered a crowd of hundreds to hear their speeches. Most of the crowd would never have set out to attend a suffrage event, but suffragists captured the audience’s attention with their spontaneity and enthusiasm.

BESAGG took notice of the success in Lynn and held their first open-air meeting in Bedford the following June, reaching a mostly male audience of approximately one hundred. Unlike previous suffrage events, these meetings were impromptu and took place outdoors in public spaces where anyone could attend. Suffragists were no longer content to encourage people to come to them, from this point forward they went out and met people where they were: city squares, rural towns, factory yards, immigrant neighborhoods, the list goes on.

Open-Air Meetings

Suffragists’ ability to improvise was key to the success of these open-air demonstrations. For example, when government officials banned suffragists from speaking to the crowds on Nantasket Beach, they simply carried their banners into the sea and spoke to beachgoers from the water.

BESAGG president Susan Fitzgerald was thrilled with the response their open-air meetings received and immediately organized a statewide “trolley tour” in August 1909. She and several other suffragists criss-crossed the state at a grueling pace, resting only on Sundays. They delivered nearly 100 speeches and reached an estimated 25,000 people. Wherever they stopped, they recruited attendees to establish a local headquarters and continue the suffrage work.

Margaret Foley Takes to the Sky

Labor movement suffragists also helped take suffrage organizing from the parlor and lecture hall to the town square and city streets. Margaret Foley was born to a working-class family in Dorchester and joined the Hat Trimmers’ Union while working in a hat factory. She later became a board member of the Boston Women’s Trade Union League and a field manager for the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association.

A fervent believer in the power of open-air meetings to persuade people to support suffrage, Foley worked both behind-the-scenes to organize demonstrations and in the spotlight, delivering impassioned appeals about the benefits of votes for women.

Foley was best-known for her role as the suffrage movement’s “heckler-in-chief.” Like the English suffragettes who disrupted political speakers, Foley trailed anti-suffrage politicians throughout Massachusetts, loudly demanding to hear how they would vote on suffrage issues. It’s believed that her tactics contributed to more than one anti-suffrage official losing reelection!

Not limiting herself to the streets, Foley even took to the sky to deliver the “Votes for Women” message. In 1910, she went up in a hot-air balloon in order to distribute suffrage leaflets over the Commonwealth. Other suffragists tried attention-grabbing stunts as well. For instance, Florence Luscomb and Mabel Ewell emulated the English suffragettes who took to the street as “newsies” when they sold copies of The Woman’s Journal in November 1909. It likely marked the first time that suffragists campaigned on the streets of Boston!

Claiborne Catlin's shoulder sash. Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Claiborne Catlin Crosses the State on Horseback

In 1914, NAWSA tasked suffragist Claiborne Catlin with filling Boston’s Tremont Temple for an upcoming suffrage rally. She initially hired a man to ride through downtown Boston on horseback to publicize the event, but when he backed out on account of rain, Catlin did the job herself and succeeded in turning out a large crowd. The tactic’s effectiveness inspired Catlin to ride across the state on horseback that summer in order to reach the residents of rural parts of Massachusetts.

From July to October 1914, she rode across Cape Cod as well as southeastern and central Massachusetts. All told, Catlin traversed more than 500 miles, visited 37 cities and towns, and organized nearly 60 meetings. A trip of this scale was a challenging undertaking for a woman traveling alone. She encountered poor weather, horses that went lame, and (at least once) the threat of assault from a drunken man. Still, she described the trip as “worth every speck of tiredness, every minute of loneliness, every throb of fright.”

Question: Do you think Catlin changed minds about whether or not women should vote by campaigning across the state on horseback? Why or why not?

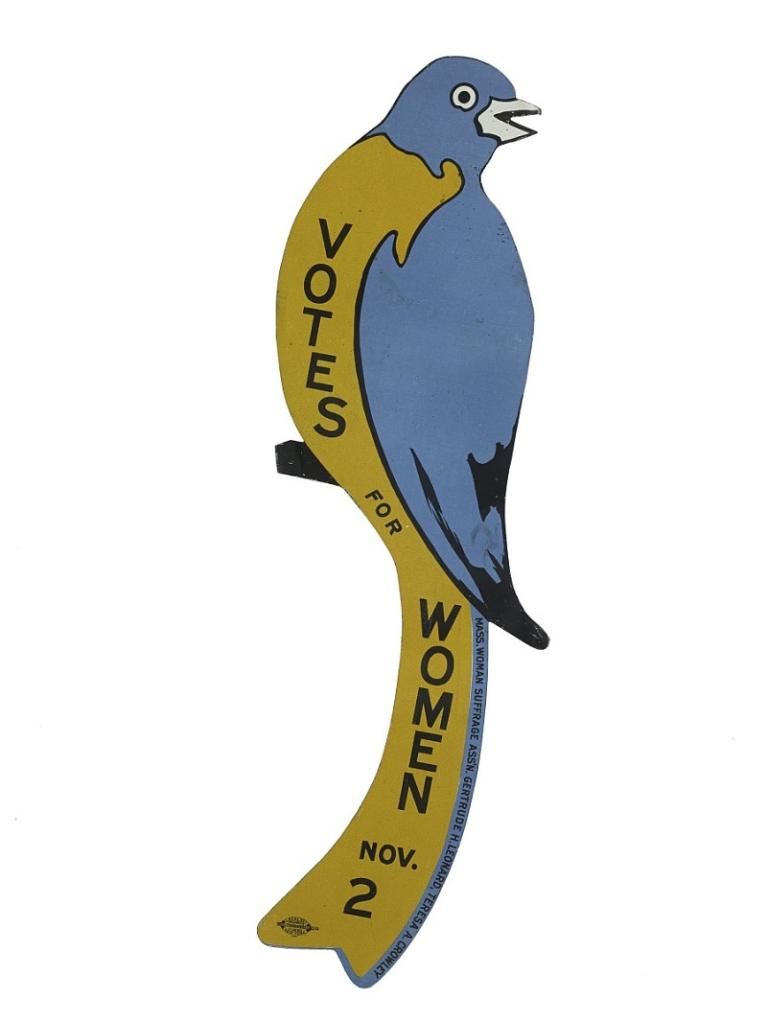

Bluebirds Blanket the Commonwealth

While individuals like Foley and Catlin covered as much ground as they could, Massachusetts suffragists found another creative way to make their presence known across the Commonwealth. To raise awareness in the lead-up to the 1915 suffrage referendum, they chose bluebirds as their official symbol. Florence Luscomb designed the iconic 12-by-4 inch tin bluebird signs, pictured here, with the message "Votes for Women" and a reminder of Election Day on November 2, 1915.

Bay State suffragists designated July 17, 1915 "Suffrage Bluebird Day" and instructed supporters to post the bluebird signs on walls, fences, and windows across the Commonwealth. It's estimated that 100,000 bluebirds blanketed Massachusetts that summer – a powerful visual demonstration of the suffrage movement's growing momentum.

Parades

One tactic that suffragists are sometimes remembered for is their parades. Massachusetts suffragists were no exception – they held many parades to publicly and visibly demonstrate the large number of supporters they had amassed over decades of organizing. The two biggest suffrage parades in the Bay State took place in Boston in 1914 and 1915.

American suffragists were inspired by the parades of English suffragettes, but parading was also an important part of civic and political culture in the United States. Labor groups organized parades to celebrate May Day, immigrant communities held parades to display their ethnic pride, and cities and towns put on parades to commemorate the Fourth of July.

Alongside open-air meetings and campaign tours, suffragists began organizing parades in 1908, when the first suffrage parade took place in New York City. As with the other new tactics discussed above, the public nature of parading carried great significance for women, particularly parades advocating for voting rights. 19th-century notions of propriety still dictated that respectable women should remain in the private sphere of the home, rather than parade publicly in the streets. Parading, like voting, represented breaking free of the constraints society placed on women.

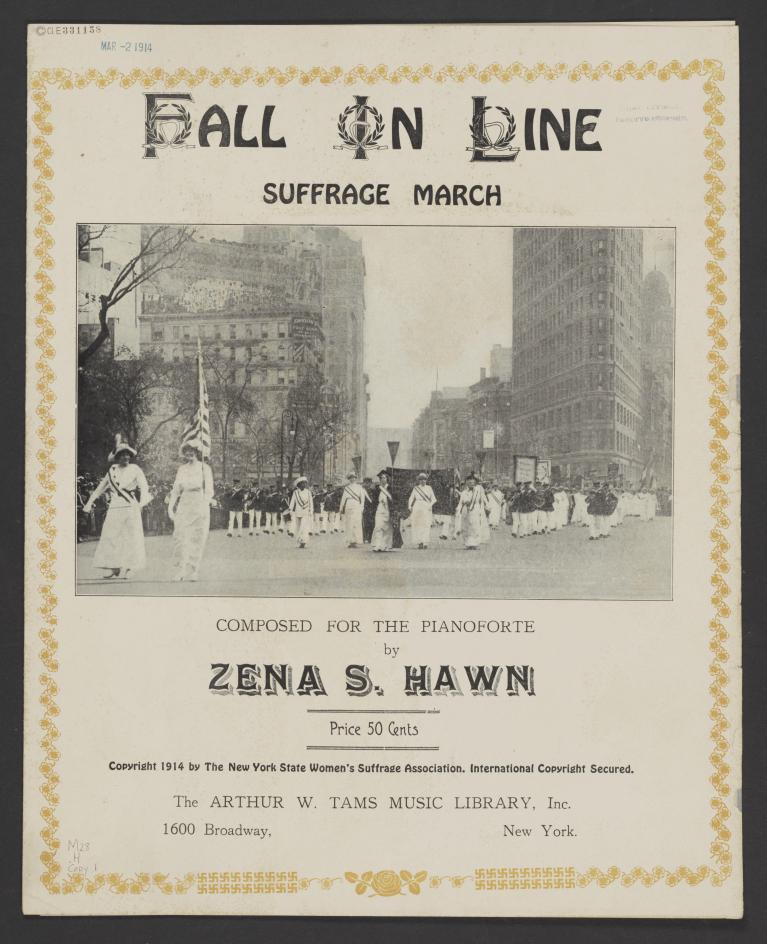

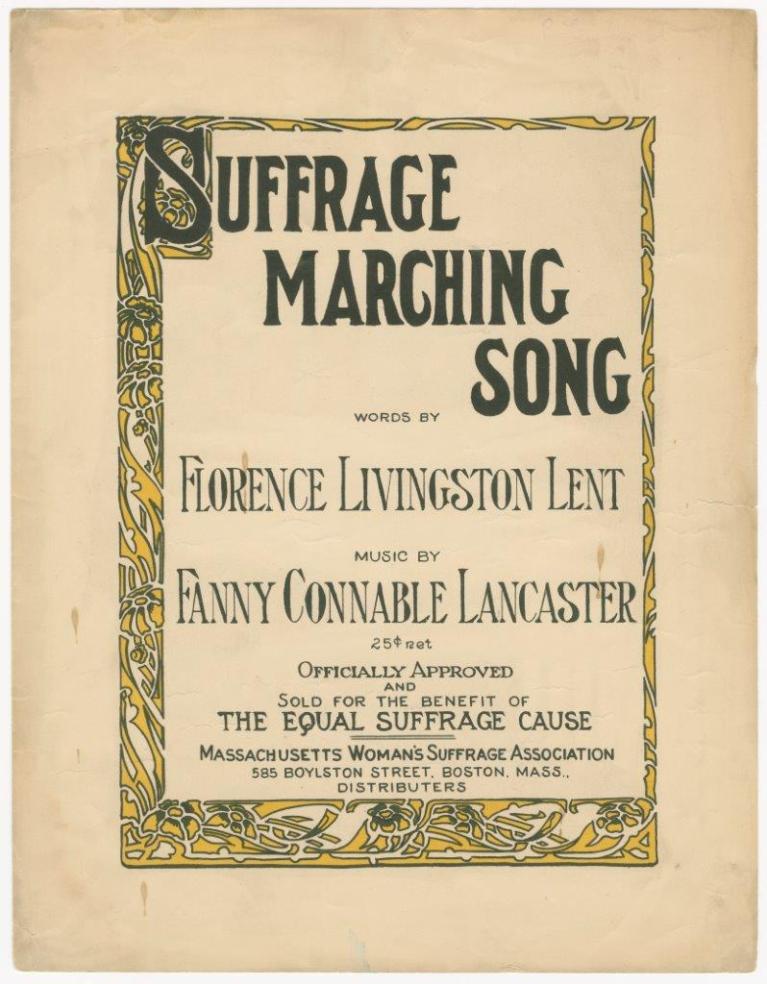

Marching Music

Suffrage parades weren't complete without marching music. Suffrage organizations sold copies of their sheet music to raise money, like the Massachusetts Woman's Suffrage Association did with "The Suffrage Marching Song."

New York State Women's Suffrage Association sheet music. Arthur W. Tams Music Library, Inc., copyright 1914. Library of Congress, Music Division.

Massachusetts Woman's Suffrage Association sheet music. Boston, MA, 1914. DeGolyer Library, SMU.

Fall in Line (Suffrage March), 1914

Listen to the audio of "Fall in Line (Suffrage March)" to hear one of the rousing melodies that accompanied parading suffragists.

Performer: Victor Military Band

Writer: Zena S. Hawn

Boston Takes to the Streets

In the spring of 1914, Massachusetts suffragists organized a parade to kick off their campaign to win the 1915 referendum on votes for women. On May 2nd, which NAWSA had designated National Suffrage Day, parades took place across the country. Boston’s parade boasted more than 12,000 marchers and a remarkable crowd that was estimated to include 250,000-300,000 spectators! For comparison’s sake, the Women’s March in 2017 featured approximately 175,000 attendees.

Boston's 1915 Suffrage Parade

On October 16, 1915, a few weeks prior to the November 2nd referendum, Massachusetts suffragists held Boston’s second parade. The “Victory Parade” (as it was aspirationally named) included 15,000 marchers and the crowd was reportedly twice as large as the previous year’s, with half a million spectators! The Boston Globe’s headline the following day read: “Suffrage Victory Parade Sets a Record for Enthusiasm.”

The Boston Sunday Globe, "Suffrage Parade Sets Victory for Enthusiasm-- Nearly 9000 in The Line" Suffrage at Simmons.

Protesting the President

Silent Sentinels

In January 1917, the National Woman’s Party (NWP) pioneered a bold new tactic in order to push for federal approval of a constitutional amendment ensuring women’s suffrage nationwide: picketing daily at the White House! They were the first group ever to picket the White House. The suffrage protesters stood silently in front of the White House with signs that did their speaking for them. The “Silent Sentinels,” as they were known, symbolically demonstrated how the inability to vote deprived citizens of a voice in their government.

Many people objected to the White House protests, especially after the United States entered World War I that April. Though they were criticized for picketing the President during wartime, the Silent Sentinels persisted. On June 22nd, police arrested suffragists Lucy Burns and Brookline-native Katharine Morey for blocking pedestrian traffic. Protests continued six days a week for over two-and-a-half years (in pouring rain, freezing cold, and sweltering heat). Nearly 2,000 suffragists from 30 states joined the pickets. In total, about 500 protesters were arrested and 168 were jailed.

Eventually, word got out about the hunger strikes by many of the jailed suffragists, as well as the tortuous force-feedings they endured at the hands of prison officials. News of the conditions in the jail garnered major press attention and led to public outcry about the mistreatment the suffragists experienced.

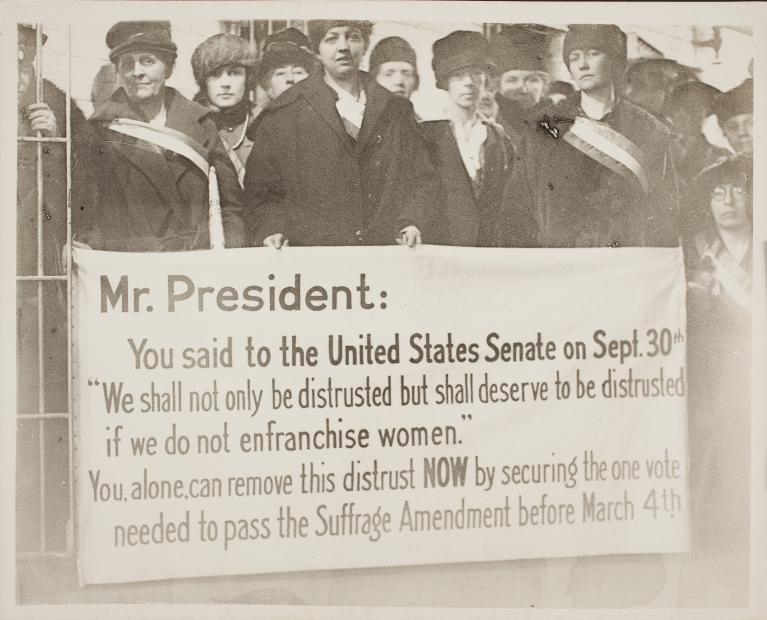

Boston Suffragists Confront the President

On February 24, 1919, NWP members in Boston employed the same strategy, protesting President Wilson when he arrived in the city after taking part in the Paris Peace Accords. Katharine Morey and 21 other suffragists, nearly all from Massachusetts, marched to the State House with banners calling on the President to secure the single remaining vote needed to pass the federal suffrage amendment.

However, Boston police arrested the suffragists for loitering before President Wilson arrived. NWP suffragists held a corresponding protest on the Boston Common, where they burned copies of President Wilson’s remarks. Three women were arrested there. When the protestors refused to pay the five dollar fines they each received, the judge sent them to the Charles Street Jail for eight days.

Some of them were released early when, against their wishes, an anonymous man paid their fines. Morey’s mother speculated that there was in fact no such man, but that the authorities did not want the attention that would come from imprisoning high-profile suffragists.

The women arrested at the 1919 Boston protests were the only suffragists jailed for picketing anywhere outside of Washington, D.C. and they were the last ones in the nation imprisoned for the cause of suffrage.

Winning the Fight

Bay State suffragists embraced a host of new tactics in the early years of the 20th century, but they continued to utilize the tried and true ones as well. In the days following the state’s 1915 referendum, in which men rejected women’s suffrage by a two-to-one margin, Massachusetts suffragists met in Faneuil Hall to determine their strategy going forward. No longer hopeful about achieving suffrage at the state level, they opted to pursue voting rights at the federal level with a constitutional amendment. As the attention on passing and then ratifying a constitutional amendment heated up, NAWSA members focused their energy on electing pro-suffrage officials and lobbying legislators to support the amendment. They were led by the group’s new chief lobbyist in Washington, D.C., the Boston native and Radcliffe graduate who had created the College Equal Suffrage League, Maud Wood Park.

Unseating a U.S. Senator

Massachusetts suffragists played a crucial role in passing the suffrage amendment by working tirelessly to defeat anti-suffrage U.S. Senator John W. Weeks in the 1918 election. On October 1, 1918, the Senate’s vote to pass the suffrage amendment failed by just one vote, inspiring suffragists to target Weeks and fill his seat with a pro-suffrage candidate. They had just five weeks before Election Day.

The newly formed Non-Partisan Suffrage Committee, led by cartoonist Blanche Ames Ames, spearheaded the effort to defeat Weeks. Ames and her committee knew that attacking Weeks solely on his suffrage record could backfire, as anti-suffrage sentiment was still strong in the Commonwealth. Instead, they publicized every instance from his voting record where they could portray him as out-of-step with popular opinion: his votes against the eight-hour workday, the extension of credit to farmers, and the direct election of senators, among others. Meanwhile, labor suffragists rallied union women, Catholic and Jewish suffragists canvassed their neighborhoods, and the committee wrote to 35,000 suffragists in Massachusetts, calling on each of them to persuade one enfranchised male friend or relative to vote against Weeks.

Their dedicated campaign was successful and Weeks lost his Senate seat on November 5th. Along with another flipped seat in Delaware, suffragists now had the votes in the Senate to pass the 19th amendment. On May 19, 1919, the U.S. House of Representatives approved the measure and on June 4th, the Senate followed suit.

Now, the amendment went to the state legislatures for ratification. Once 36 states ratified, the amendment would be enshrined in the United States Constitution. Experienced activist Maud Wood Park, who had led congressional lobbying efforts for NAWSA since 1916, helped campaign for ratification nationwide. Park had fostered a well-oiled lobbying machine by teaching her fellow suffragists to gather detailed information on the representatives they sought to persuade and to adhere to her strict “lobby rules:”

"Six Don’t's for Lobbying:

1. Don’t tell all you know.

2. Don’t tell anything you do not know (don’t listen to rumors and repeat them).

3. Do not repeat even a slight remark that has been made to you in confidence.

4. Don’t lose your temper.

5. Don’t nag.

6. Never give up.”

Maud Wood Park

Ratification in Massachusetts

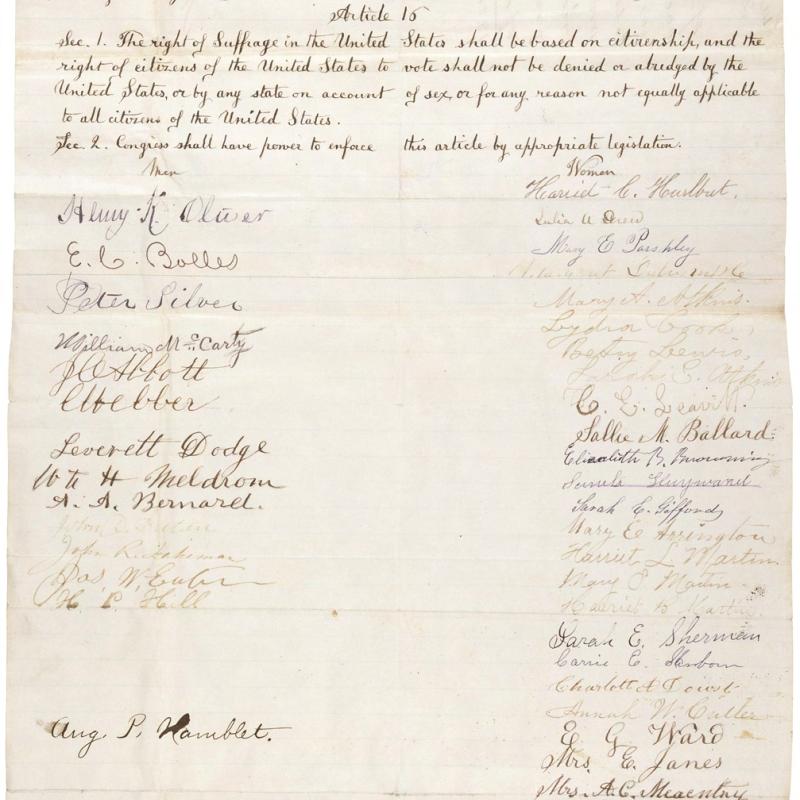

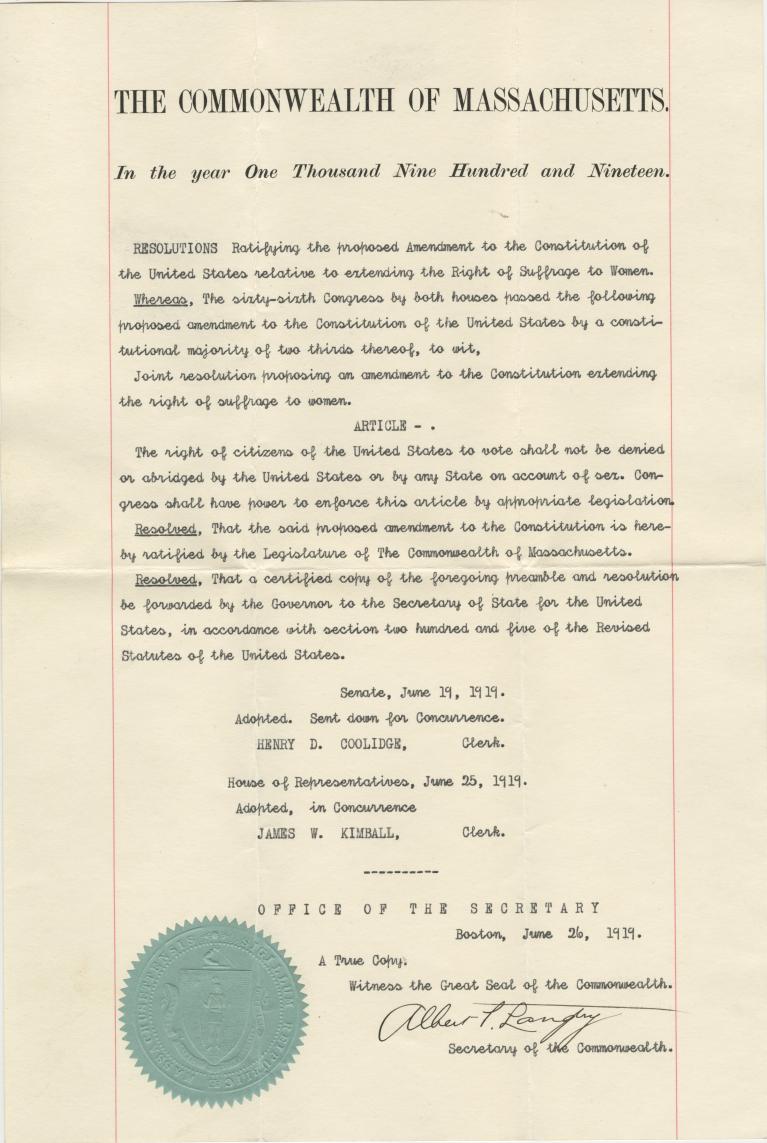

In order to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the 19th amendment, Bay State suffragists turned to the same tactics their foremothers used more than half a century prior: petitions and hearings. Anxious about the amendment’s prospects in the Massachusetts state legislature, they made sure to demonstrate their strength in numbers. Florence Luscomb and a team of volunteers submitted a petition with so many signatures that it left legislators in awe. Next, nearly 500 women showed up to support the amendment at its legislative hearing. Alice Stone Blackwell, Margaret Foley, and Katharine Morey all spoke in favor of ratification.

Their efforts paid off. On June 25, 1919, Massachusetts became the 8th state in the nation to ratify the 19th Amendment.

The suffrage amendment still faced a tough road ahead though. To take effect, 36 of the 48 states needed to ratify the amendment. Over the next year, 27 more states approved the measure, but eight states rejected it. With passage unlikely in the other four remaining states, it seemingly all came down to Tennessee. On August 18, 1920, the Tennessee state legislature ratified the 19th Amendment by a margin of only one vote. (In a reversal of his previous stance, a 24-year-old Republican state senator named Harry Burns voted for women’s suffrage – based on the advice of his mother.)

Eight days later, on August 26th, the 19th Amendment was officially certified. More than 70 years after the suffrage campaign began, the right of women to vote was officially added to the United States Constitution…just in time for women to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

The Campaign Continues…

The 19th Amendment, adopted in 1920, made it illegal to deny the right to vote to anyone on account of their sex in federal or state elections. However, many women – and men – of color continued to be disenfranchised by other laws. Native Americans and Asian immigrants across the country faced barriers due to laws that denied their citizenship, while African Americans in the South faced discriminatory laws and prejudicial enforcement that largely prevented them from voting. The fight for women’s suffrage was a massive undertaking that resulted in the single greatest expansion of voting rights in U.S. history, enabling 20 million American women to vote. But the larger campaign for equal voting rights for all continues to this day.

Members of the Chinese Progressive Association marching in Boston, 1983. Northeastern University Library, Archives and Special Collections.

Question: What issues concerning voting rights have you heard about in the news lately?

Technology and world events have also affected how we vote today. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states, including Massachusetts, made it easier to vote by mail to allow for social distancing. And in 2022, the Commonwealth approved secure electronic voting for blind or low-vision individuals, making voting more accessible to them than ever before. Efforts to expand translation services for non-English speakers continue today, and in several Massachusetts communities, there are politicians and organizations advocating to lower the voting age to 16 in local elections!

Conclusion

Question: What can today’s activists learn from the suffragists’ strategies and tactics?

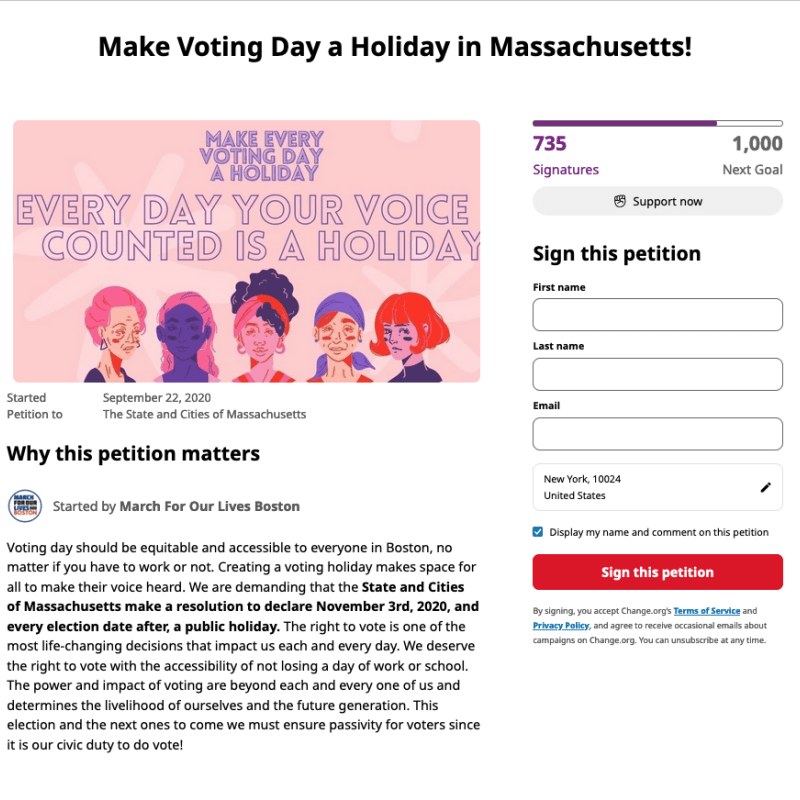

The technology and media that political activists use have changed a great deal since the era of the suffrage movement, but much of the overarching strategy behind these campaigns remains the same today. Change.org petitions circulated via email have replaced handwritten petitions delivered in person to the legislature, and social media posts have replaced broadsheets and fliers, but not everything is different.

While virtual meetings are now an important tool, mass in-person demonstrations like marches and rallies are still key ways for people to show support for causes they care about. Importantly, the strategy behind all these tactics remains the same: to reach new audiences, grow the movement, foster solidarity among its members, and demonstrate its popular support.

Whenever we find ourselves in search of effective ways to protect and expand voting rights, we can find inspiration in the vibrant legacy of Massachusetts’ savvy and innovative suffrage advocates.

Credits

Acknowledgements

Exhibit curated by Mariana Brandman, Ph.D.

The Massachusetts Women’s History Center would like to give special thanks to the following individuals and institutions for their assistance: Grace Millet, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections; Silvia Mejia, State Library of Massachusetts; Bridget Cooley, City of Lowell, Massachusetts; Diana Carey, Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute; Wayne McCarthy, Waltham Historical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts; Jay Block and the Wallace Anderson Gallery, Bridgewater State University; Terre Heydari, DeGolyer Library, SMU; and Donna E. Russo, Historic New England.

Works Cited

“Angelina Grimke Addresses Legislature.” Mass Moments. February 21, 2005.

“Anonymous Gifts Powered the Fight for the Women’s Vote.” Philanthropy Roundtable (blog), March 31, 2021.

“Bay State Suffrage Festivals at Copley Plaza Hotel (U.S. National Park Service).”

Berenson, Barbara F. Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement: Revolutionary Reformers. United States: History Press, 2018.

Berenson, Barbara F. “Perspective | Politicians Beware: Crossing Women Comes at a Hefty Cost.” Washington Post, October 16, 2018.

Birnbaum, Gemma R. “‘Old Enough to Fight, Old Enough to Vote’: The WWII Roots of the 26th Amendment.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. October 28, 2020.

BlackPast. “(1832) Maria W. Stewart, ‘Why Sit Ye Here and Die?’,” January 25, 2007.

Blakemore, Erin. “Why Did Suffragists Wear White? Symbols of the Suffrage Movement, Explained.” National Geographic. March 17, 2021.

Claiborne Catlin Elliman Papers. Scrapbook: mostly clippings re: horseback trip; also correspondence, speaking permit, etc., 1914, 1919. A-75, folder 6v. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

“Concord Women Cast First Votes.” Mass Moments.

Cooney, Robert. Winning the Vote: The Triumph of the American Woman Suffrage Movement. United States: Published and distributed by American Graphic Press, 2005.

The Crisis. Vol. 10, No. 4 (August, 1915). The Modernist Journals Project. The Modernist Journals Project (searchable database). Brown and Tulsa Universities, ongoing.

Dilley, Nicholas J. “Legacy of the Voting Rights Act – Expansions of the 1970s.” The Reagan Library Education Blog (blog). U.S. National Archives. April 19, 2022.

Emanuel, Gabrielle. “Translating The Ballot For Boston Voters,” GBH. November 7, 2016.

“First National Woman’s Rights Convention Ends in Worcester.” Mass Moments. October 24, 2010.

Goodier, Susan. “Flexing Feminine Muscles: Strategies and Conflicts in the Suffrage Movement (U.S. National Park Service).”

“Historical Overview of the National Woman’s Party,” The Library of Congress | American Memory.

Kirby, Jen. "How the Radical British Suffragettes Influenced America’s Campaign for the Women’s Vote." Vox. August 19, 2020.

Kohlhofer, Merrill. “New England Woman’s Tea Party (U.S. National Park Service).”

Landrigan, Leslie. “How Louisa May Alcott Voted for the First Time in 1880.” New England Historical Society, March 29, 2019.

Levine, Sam, and Ankita Rao. “In 2013 the Supreme Court Gutted Voting Rights – How Has It Changed the US?” The Guardian, June 25, 2020, sec. US news.

Montclair History Center. “Women’s History Month: Lucy Stone,” March 9, 2021.

“More Women’s Rights Conventions - Women’s Rights National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service).” February 26, 2015.

Muncy, Robyn. “The Necessity of Other Social Movements to the Struggle for Woman Suffrage (U.S. National Park Service).”

“Music in the Women’s Suffrage Movement." Women’s Suffrage in Sheet Music. The Library of Congress.”

Oommen, Dhati. “What’s in the VOTES Act?” Harvard Political Review (blog), November 8, 2022.

Panetta, Meg. “Biographical Sketch of Mary Hutcheson Page | Alexander Street Documents.”

Porter, Corinne. “American Women and the Vote.” U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

“The Petitions of Dr. Harriot K. Hunt (U.S. National Park Service).”

Reilly, Adam. “Boston City Council Backs Letting More Teens Vote, but Push Faces an Uphill Climb.” GBH. November 30, 2022.

Reynolds, Kim. “‘Help to Make the World Better’: Lucy Stone and the First Wave Suffragettes,” August 26, 2020.

Ryan, Agnes E. The Torch Bearer: A Look Forward and Back at the Woman's Journal, the Organ of the Woman's Movement. United States: Woman's Journal and Suffrage News, 1916.

“Site of the MA Branch Office of the National Woman’s Party (U.S. National Park Service).”

Smith, Bonnie Hurd. “Lucy Stone.” Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

Smith, Meghan. “Blind and Low-Vision Voters Hail Massachusetts’ New Statewide Online Voting Option.” GBH. October 28, 2022.

Stern, Madeleine B. “Louisa Alcott's Feminist Letters,” Studies in the American Renaissance, 1978, pp. 429-452.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. United States: Boni and Liveright, 1920.

Stockwell, Noelle. “Mary Livermore (U.S. National Park Service).”

Stone, Lucy. “Woman Suffrage in New Jersey. An Address Delivered by Lucy Stone, at a Hearing before the New Jersey Legislature, March 6th, 1867,” Library of Congress.

Strom, Sharon Hartman. “Leadership and Tactics in the American Woman Suffrage Movement: A New Perspective from Massachusetts.” The Journal of American History 62, no. 2 (1975): 296–315.

“Susan B. Anthony Speech: Is It a Crime for a Citizen of the United States to Vote?” University of Missouri-Kansas City.

“Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman’s Party Suffrage Campaign,” The Library of Congress | American Memory.

Tomasi, Adam. “Maria Stewart," The West End Museum. November 18, 2021.

Van Buskirk, Chris. “17-Year-Olds May Soon Be Able to Vote in This Mass. Community.” MassLive. March 30, 2023.

“A Vote for Women: September 30, 1918.” United States Senate.

“Voting Rights Act (1965).” National Archives. October 6, 2021.

“Voting Rights for Native Americans," The Library of Congress.

Ware, Susan. “Why They Marched: Rank and File Perspectives on the Women’s Suffrage Movement." The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

“Women’s Suffrage at Faneuil Hall (U.S. National Park Service).”

Woods, Kaitlin. “Dr. Harriot Kezia Hunt (U.S. National Park Service).”

Woods, Kaitlin. “‘Make the World Better’: The Woman’s Era Club of Boston (U.S. National Park Service).”

Woods, Kaitlin. “Anti-Suffrage in Massachusetts (U.S. National Park Service).”